— True West Archives —

Tom Jeffords leans on the bar of a saloon in Mesilla, New Mexico Territory, whiskey in one hand and a woman on the other. Will Harden (modeled after gunfighter John Wesley Hardin) glares and says, “Jeffords, you’re a rotten Indian lover.”

Jeffords pushes the woman behind him as his other hand hovers over his gun. Jeffords doesn’t want trouble, but Harden goes for his gun. Tom shoots the pistol out of Harden’s hand.

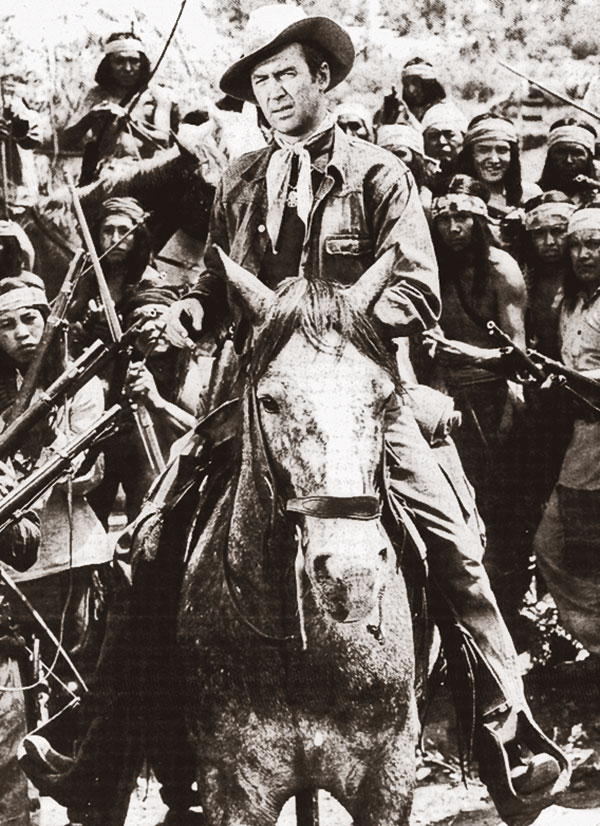

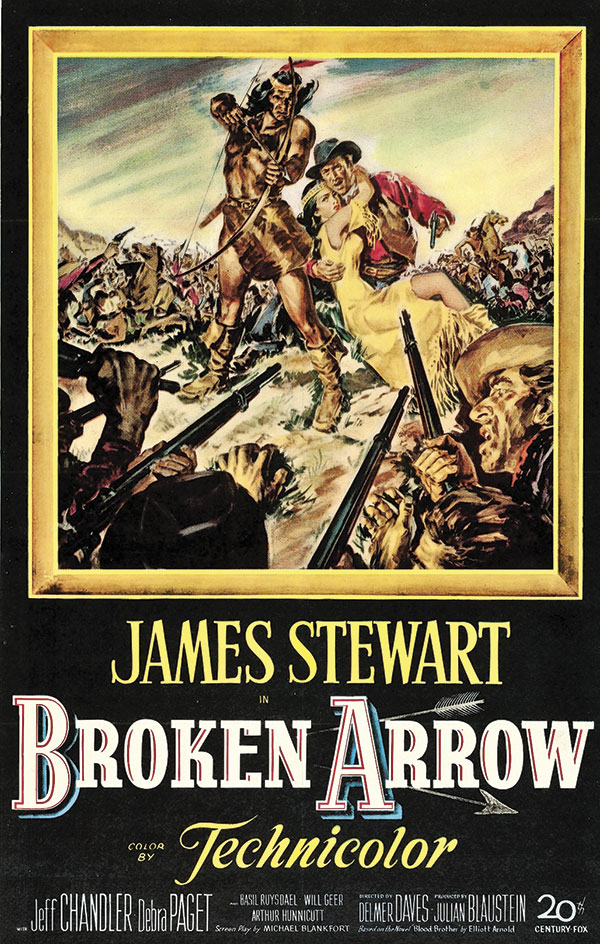

Folks know Thomas Jefferson Jeffords from the 1947 novel, Blood Brother, by Elliot Arnold, and from the 1950 movie based on that novel, Broken Arrow, starring Jimmy Stewart and Jeff Chandler. John Lupton and Michael Ansara played these same roles for the 1956-58 TV series. Each of these tellings contributed to the legend that, if not quite true, helped to develop a sense of the real-life Jeffords. The frontiersman did not need the gilding that Arnold and Hollywood put on him.

The Gunfight and the Wedding

The gunfight between Jeffords and Harden never occurred. Arnold created this scene so the public would see Jeffords as a courageous frontiersman, a hero in the style of Roy Rogers, “King of the Cowboys.” Jeffords could have killed Harden, but showed mercy in sparing his life.

Arnold’s account also established Jeffords as a friend to Apaches. He was. Yet to communicate a closeness of spirit between Jeffords, Cochise and the Chiricahua Apaches tribe to an audience, the movie depicted a marriage between Jeffords and a female relative of Cochise.

The marriage never took place. A wedding would have created trouble, and the Apache woman’s family would have expected favors that Jeffords would not have been authorized to grant.

— Broken Arrow still courtesy Twentieth Century-Fox Film —

Blood Brother to Cochise

In February 1914, Jeffords’ obituary identified him as a blood brother to Cochise. Perhaps the source was Cochise County pioneer Billy Ohnesorgen, who called Jeffords “no-good, a filthy fellow—filthy in his way of living—lived right among those damn things [Apaches]…was a blood brother or something of Cochise.”

Ohnesorgen had reason to dislike the Indian agent. When Ohnesorgen violated the reservation and destroyed Apache property, Jeffords sided against him.

Cochise and Jeffords were indeed close. Cochise called Jeffords chickasaw (brother), and he treated him as one. The Chiricahuas knew to treat Jeffords as if he were Cochise’s brother. A dying Cochise asked Jeffords if he thought they’d meet again “up there.”

But no evidence supports the claim that the Apaches practiced a mystic blood brother ceremony, despite Hollywood’s portrayal of Jimmy Stewart and Jeff Chandler performing the blood brother ceremony in Broken Arrow.

Although Elliott was clearly familiar with Apache ethnography and demonstrated such in his Blood Brother novel (for instance, he correctly recorded the sunrise ceremony), he also invented the dubious blood brother ceremony to cement in the reader’s mind that Jeffords and Cochise were close friends who shared a deep bond of trust.

Jeffords Makes Peace

Jeffords was superintendent of the mail from Tucson, Arizona Territory, to Socorro, New Mexico Territory, during 1867 to 1869, after the Butterfield Overland Mail moved north to South Pass in Wyoming in 1861. The service offered two express riders per week and soon added a stagecoach—a two-horse buckboard. Jeffords drove the stage on the road Butterfield had used, and Cochise and his Apaches attacked it at least once while Jeffords was on board.

Cochise may have killed 22 men while Jeffords worked the mail, but the record shows that the Apaches pursued few mail riders and killed only one. After Jeffords left the job, Cochise and his Apaches attacked again, killing six men.

That assault led to a month-long pursuit in October 1869 that culminated in the Battle of Chiricahua Pass, near Sonoita Creek in Arizona Territory, after which the Army decorated 32 troopers with the Medal of Honor. Cochise told Joseph Alton Sladen, Gen. Oliver O. Howard’s aide, that he’d never attack the mail again; it led to too much trouble.

Jeffords would have had little reason to approach Cochise about making peace for the mail. Apache sources say negotiations took place after Jeffords left the mail and was prospecting in Apache country.

The story goes that Cochise’s warriors captured Jeffords and took him to the chief, who was so impressed with his courage that he granted Jeffords license to prospect in his land. This is unlikely. The Apaches didn’t like people scratching into the earth. Cochise knew that prospecting led to towns and mines.

Fred Hughes, who was Jeffords’ clerk at the Chiricahua agency, knew when the two had first met, in June 1871. A peace commission passed through Cochise’s camp west of Cañada Alamosa, while the chief and his warriors were raiding in Mexico. The Army rounded up all of the people, except for Cochise’s immediate family, and escorted them to a reservation.

After a bad spring, the Apaches were nervous that summer and thus likely to kill anyone approaching them. Civilians had recently murdered many of them in the Camp Grant Massacre.

The Indian commissioner needed someone courageous to find Cochise and invite the chief to talks. When no one else would take on the task of riding into Cochise’s camp alone, Jeffords volunteered. The two met, but Cochise was afraid to travel alone with his family. Three months later, Cochise came in, and his friendship with Jeffords flourished.

Jeffords learned to speak some Apache, between September 1871 and March 1872, when Cochise was camped near the Cañada Alamosa Chiricahua reservation. The chief had come in to parley.

Jeffords’ friendship with Cochise became so widely known that at least five different people—the agency clerk, ranchers, Apaches and scouts—told Gen. Howard that Jeffords was the only man who could take him to Cochise.

In 1872, when Jeffords brought Gen. Howard to Cochise Stronghold, Cochise’s aerie high in the Dragoon Mountains, the chief greeted his brother by throwing his arms around him.

“Can I trust this man?” Cochise asked.

“I think so,” Jeffords replied, “but I won’t let him promise too much.”

— Courtesy Twentieth Century-Fox Film —

Captain of Trust

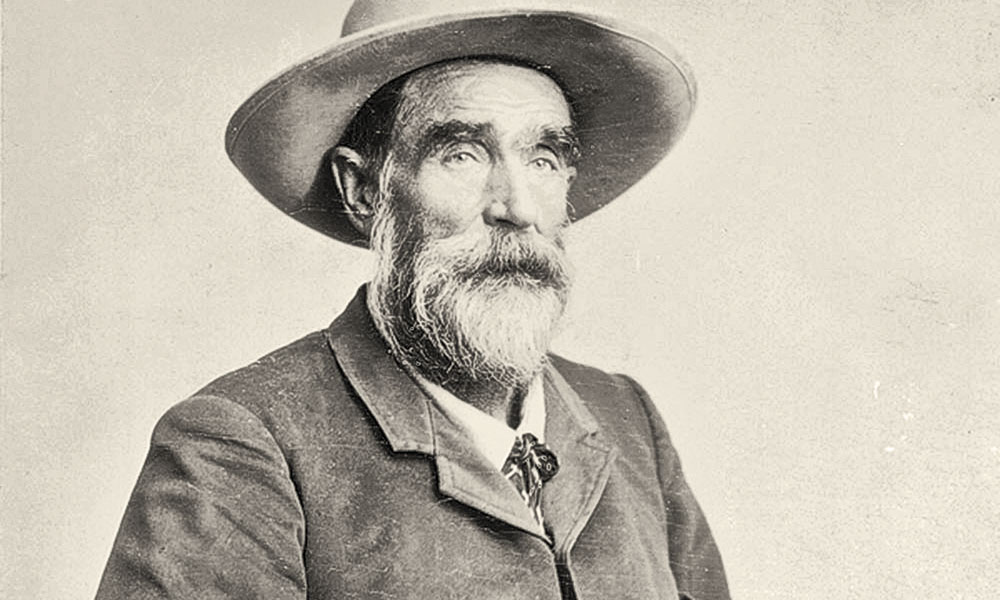

Jeffords grew up in the lakeport town of Ashtabula, Ohio. He and four of his brothers worked the Great Lakes, three of them as captains. In 1856, Jeffords commanded a ship that capsized. Only 24, he had risen to the rank of captain. He survived the disaster and went on to gain the respect of his men.

Lake sailing is not like sailing the salt seas. The crews were small: captain, mate, cook and two or three deck hands. They ate fresh food in the captain’s cabin. They made runs, not voyages, consisting of a few days to a few weeks, at the end of which the crew took its pay while the boat was unloading and the captain hired a new crew.

The men went home or found other work in the winter when the lakes were frozen. This employer relationship put special demands on the officers. They had to gain men’s trust and respect quickly, regardless of social class and ethnic group. They had to appear fearless so their crew would obey their orders instantly in dangerous situations. At the same time, they had to be companionable during meals while maintaining their elevated positions as officers.

A fellow frontiersman said of Jeffords that he was a man who always arrived with friends, was always welcome and was always in positions of leadership. The lake life prepared Jeffords for winning the trust and respect of Cochise and the Chiricahuas. His special status with the tribe continued after the death of his friend. To this day, a medicine bundle rests on his grave in Tucson.

In Blood Brother, Arnold claimed Jeffords sailed the Mississippi. Perhaps he did. Arizona Territory Gov. Anson Safford made that claim as well, in his impossible and confused biography of Jeffords. Yet even if Jeffords did sail the Mississippi between 1856 and 1859, he probably did not captain a steamboat. These mechanical marvels were huge floating hotels with crews of up to 80. Three years would not have been enough time for Jeffords to learn the new skills required of steamboat captains.

In 1859, Jeffords built the road from Leavenworth, Kansas, to Denver, Colorado. He acted as a surveyor, having learned useful skills of navigation as an officer on the lakes. Starting as a Fifty-Niner in the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush, Jeffords pursued prospecting and mining throughout his life.

In March 1862, the California Column, a brigade-sized unit, was marching toward the Rio Grande. The Union commander in New Mexico Territory needed to know when they would arrive. The Confederate Army in control of Tucson and the Southern Emigrant Trail in Arizona Territory stood between them. He needed a man who knew Stephen Watts Kearny’s Gila River Route brave enough to make the 500-mile ride through Apache country. Jeffords was the man. He rode alone, risking his life, on a desperate, horse-killing ride.

— Published in History of Arizona by Thomas Edwin Farish —

Life After the Reservation

In 1876, the Indian Service fired Jeffords as agent for the Chiricahua reservation. The newspapers made many accusations of what caused the firing, but none substantiated. He and Cochise and Cochise’s sons had kept the peace. Raiding had stopped north of the border, stolen livestock was returned and they even once unceremoniously took a captive away from Geronimo, although they didn’t punish the culprits.

Jeffords returned to prospecting and mining, and even owned a one-ninth share in the Copper Queen. He was the post trader at Fort Huachuca and headed a company that sought to bring artesian water to homes in Tucson. Even though the Indian Service had fired him, the Army still called on Jeffords to scout and to calm the Chiricahuas on their new reservation.

In 1892, Jeffords moved to the Owl Head Buttes 35 miles north of Tucson, where he lived the rest of his life. That locale is where his path became entwined with that of confidence trickster, Alice Rollins Crane, later Madam Morajeski, wife of a Russian faux-count. Jeffords worked 22 claims in the Owl Head Buttes area and apparently made a reasonable living. Between 1909 and 1912, he transferred these claims to the Morajeskis, a business arrangement that may have left Jeffords a pauper by the time the 84 year old died, on February 19, 1914.

Brothers to the End

Jeffords and Cochise went down in history for successfully teaming up to create a homeland reservation.

The pair was each others’ constant companion, to the point that the Army came to mistrust Jeffords. On March 20, 1872, when Col. Gordon Granger, military commander of New Mexico Territory, met with Jeffords, Dr. Henry Turrill, who was present, whispered to one of the colonels: “If this goes south, I’ll kill Jeffords; you get Cochise.”

In 1876, young firebrands, including perhaps Geronimo, went on a drunken spree and killed a bunch of innocent people. As a result, Cochise and his people lost their reservation and Jeffords lost his job.

Cochise had died two years earlier. Only his people and Jeffords knew the location of the Chiricahua Apache chief’s grave. Jeffords never betrayed the secret of his friend’s final resting place.

Doug Hocking grew up on the Jicarilla Apache Reservation in New Mexico and served as an Armored Cavalry officer. He penned the first full-length biography of Tom Jeffords, published this May by Two Dot. Writing from the land of Cochise, Hocking continues work on his novels; his latest novel is Massacre at Point of Rocks.