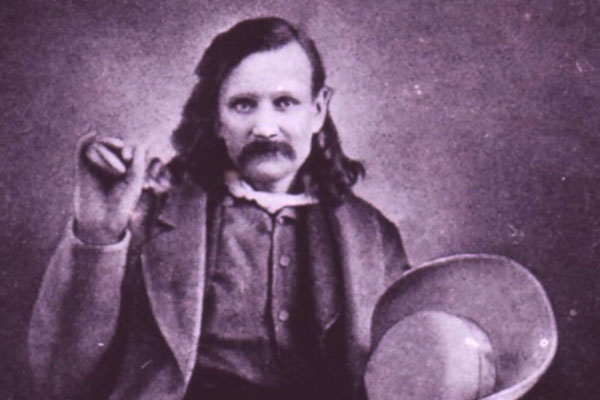

Jack Swilling is a name that goes almost unrecognized by Arizonans today. Much of what is known about him comes from tall tales, lies and half-truths. Jack himself could color a story redder than a Navajo blanket. In that he was no different from countless other yarn spinners on the American frontier who created the art of verbal hoaxing better-known as the tall tale.

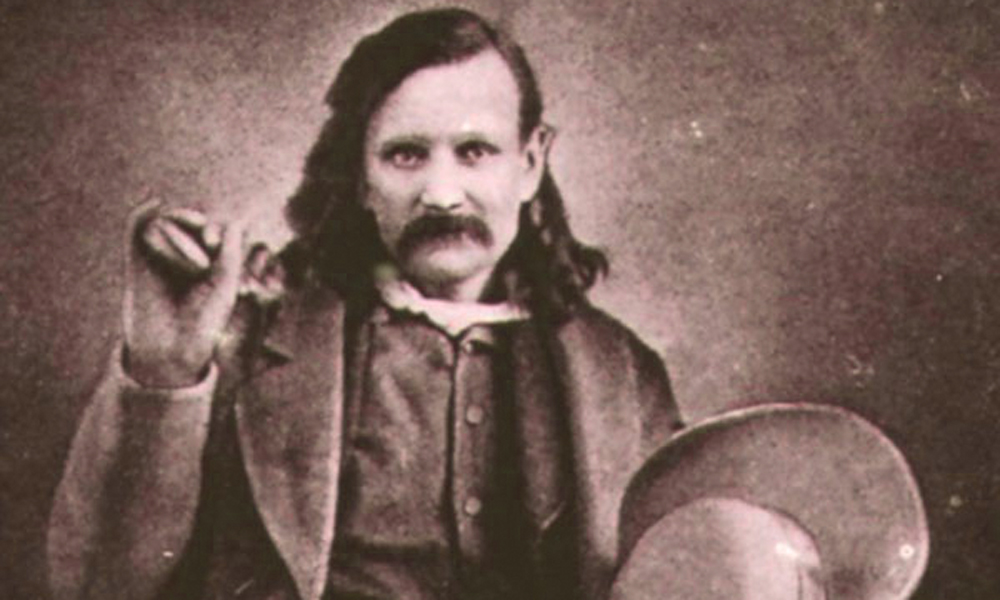

A tall, powerful man, he was brave, generous to a fault, a wonderful family man and for the most part was respected by his contemporaries. Swilling was the stuff of legends and he was truly a product of his time. Then, why is he barely remembered today?

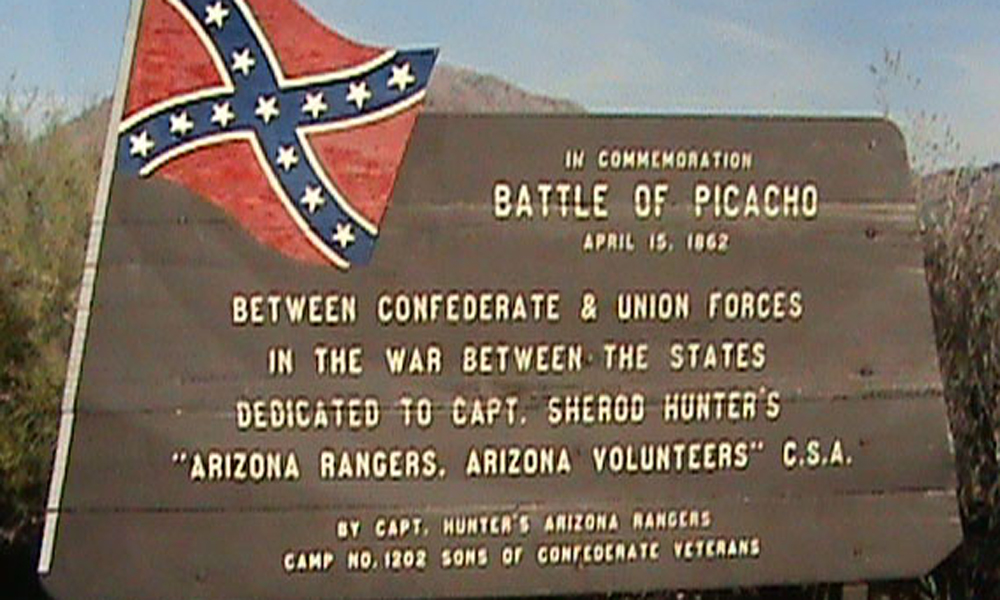

One is want to call the ubiquitous adventurer the “Forrest Gump” of territorial Arizona. He left his footprints on just about every important event that occurred in pristine Arizona during the 1860s. He participated in three of the most famous gold discoveries in Arizona history and was a Confederate officer in Arizona during the Civil War. Along with being the father of modern irrigation in the Salt River Valley, he was a founding father of Wickenburg, Prescott, and Phoenix. Some historians even credit him with naming the future state capital.

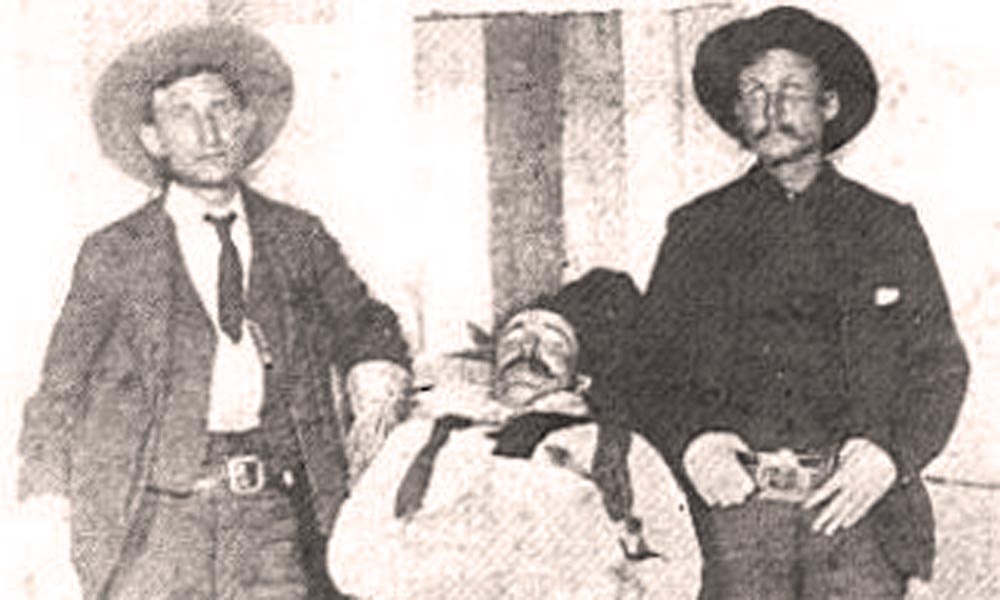

That’s quite a resume for a man who’s hardly a footnote in Arizona history books. It may have something to do with his dark side. At times he was prone to violence and it’s even been said he was insane. It’s claimed that during a drunken rage he killed a man with a shotgun in Wickenburg then scalped him.

Swilling was born April 1st, 1830 in South Carolina. His family moved to Georgia when he was fourteen. In June 1847 joined a regiment bound for the Mexican War where his regiment fought in several battles. After the war he returned to Georgia and later moved to Alabama where he met and married a sixteen-year-old girl named Mary Jane Gray.

In 1854, a year after the birth of his daughter, Jack’s skull was fractured from a blow from a large pistol. A bullet wound from a previous injury was also causing him severe pain. Morphine was prescribed to ease the pain but it also brought an addiction. He began combining whiskey and opiates with the drug and thus began his path to eventual self-destruction and an early death.

Jack and his wife split up for reasons unknown in 1856 and he headed west. He would never see her or his daughter again.

Jack’s whereabouts for the next two years are uncertain but he showed up again in 1858 working as a teamster on the Leech Wagon Road that went from El Paso to Yuma. It was during this time that he saw Arizona for the first time. By August of that year he was in California searching for gold.

Colonel Jake Snively’s 1858 gold strike on the Gila River a few miles east of Yuma eventually drew Jack to the new boom town of Gila City. Constant raids by Tonto Apache on the prospectors led to the forming of a militia called the Gila Rangers. The men elected Jack leader and on January 7th, 1860, while leading a punitive expedition against the Apache, Jack and his rangers came upon the Hassayampa River, previously unknown to white men. The area was too remote and dangerous to explore for gold but Jack would return at a later date.

New gold discoveries in the Pinos Altos area in today’s western New Mexico drew Jack to the area in 1861. The prospectors were being raided constantly by Apache bands under the leadership of the wily Mangas Colorados. A militia calling itself the Arizona Guards was raised and Jack was elected first lieutenant. Over the next few months he led them on punitive expeditions against the raiders.

The firing on Fort Sumter in the spring of 1861 would bring a brand new adventure to Jack’s storied life.