— Illustrations by Bob Boze Bell —

May 10, 1871

Tracking a party of rough hombres, Alameda County Sheriff Harry Morse and San Jose Deputy Theodore “Sam” Winchell approach a ranch house in California’s Saucelito Valley, near St. Mary’s Peak. Reining up outside a rock corral, they dismount and ask a vaquero, who is working in the corral, for a drink of water.

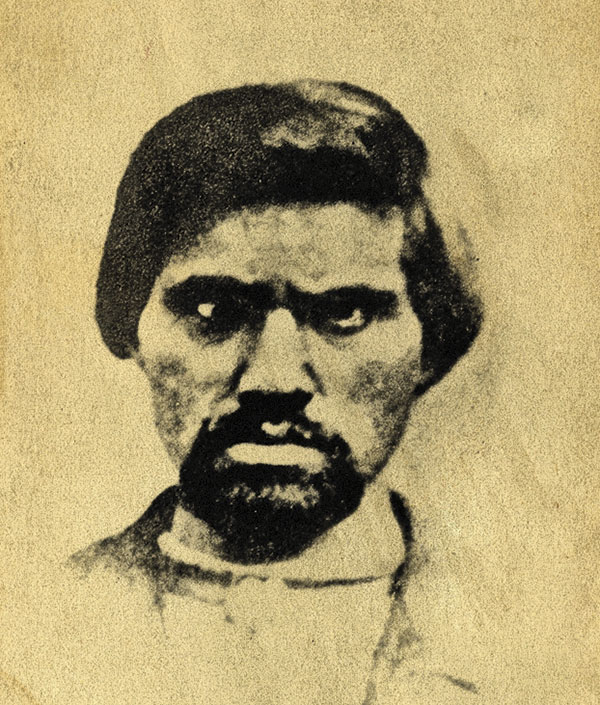

Following the worker into the house, Morse and Winchell encounter a roomful of natives. Morse is stunned as he immediately recognizes the outlaw they are looking for: Juan Soto—bandido supremo—who is sitting at a table, talking with two other men.

The sheriff jerks his pistol and barks, “¡Manos arriba!” [Put up your hands!]

But Soto doesn’t move, even after Morse repeats the command twice. Yanking manacles from his gun belt, Morse hands them to his deputy and orders him to handcuff the brigand.

Paralyzed with fright, Winchell doesn’t move.

“Put them on him!” Morse angrily snaps. Seconds tick by, and still no one moves.

“Then cover him with your shotgun,” Morse barks, “while I do it!”

Instead, Winchell bolts out the door, leaving Morse to fend for himself.

Seizing the moment, a “muscular Mexican Amazon” grabs Morse’s shooting arm, while another outlaw grabs his left. “¡No tire en la casa!” they both shout. [“Don’t shoot in

the house!”]

As Morse grapples with his assailants, Soto hides behind one of his compadres so that he can unbutton his long blue soldier’s overcoat, buttoned to his knees, and retrieve his pistols from his gun belt under the coat.

Morse frees his hand and levels his pistol at Soto’s head, but the arm jockeys spoil Morse’s aim. When Morse fires, his shot only tears off Soto’s hat, which thuds into the wall.

— All photos courtesy John Boessenecker —

Morse later claims he would have definitely gotten his prey, if he shot through a shorter man standing in front of Soto instead of aiming above the man’s head so as to avoid killing an innocent bystander.

The billowing gunpowder smoke in the dimly lit room allows Soto to seize one of his revolvers and go after Morse, who has just cleared the door.

Out on the porch, Morse sprints toward his horse so he can retrieve his rifle from its scabbard, but Soto is right behind him. Morse quickly realizes he won’t make it. Turning so as not to be shot in the back, Morse drops to the ground in an effort to dodge Soto’s imminent point-blank shot.

From a nearby hill, Santa Clara County Sheriff Nick Harris sees Morse fall, but “quick as a flash, [Morse springs] erect and fire[s]. Soto, advancing with a bound, [brings] his pistol down to a level and [fires] again, and Morse [goes] through the same maneuver as before.”

To Harris, Morse looks like he has been hit by all four rounds.

Actually, Morse has been firing back at every shot. On the final exchange, Morse fires a bullet that strikes Soto’s pistol underneath the barrel. The bullet wedges against the cylinder and jams the gun. The force of the lead ball violently drives the barrel of Soto’s own gun into his face. A stunned Soto flees into the house.

Winchell sees the outlaw escaping and sends a load of buckshot in his direction, but the deputy misses.

Taking advantage of this break in gunfire, Morse scrambles to his horse and jerks his Model 1866 Winchester rifle from the scabbard. He is met by Sheriff Harris, who pulls out his Spencer rifle to join Morse in the fight.

Following a pregnant pause, two men race out of the house toward a horse hitched to a tree 40 yards out.

Sheriff Harris takes aim at the man wearing the long, blue coat, but Morse knocks up the barrel before Harris can fire; Morse has noticed that Soto, to throw off the officers, has given his coat to the man with him and is donning his friend’s hat. What neither sheriff knows is that the outlaw is sporting three fresh revolvers.

Morse raises his rifle to kill the escape horse, but the mount breaks free and evades Soto’s grasp. The horse is undoubtedly spooked by the gunfire. Soto then rushes headlong to another horse saddled some 200 yards north.

“For God’s sake, Juan, throw down your pistols!” Morse yells. “There has been shooting enough!”

Ignoring the plea, Soto continues charging toward freedom. Although Soto is virtually out of range at 150 yards, Morse flips up his gun sight, aims high and pulls the trigger. Incredibly, the “Hail Mary” bullet hits Soto and rips through his right shoulder.

Soto staggers, then the badly wounded outlaw turns to rush his adversaries. He runs with his pistols raised, hoping to cross into firing range. Sheriff Harris shoots at Soto, but misses.

Morse chambers a round and takes a careful bead. At more than 100 yards from its target, the big ’66 booms, and its spinning bullet makes a long, low arc, smacking into Soto’s forehead just above his eyes. The bandit collapses into the grass, dead.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

Juan Soto was wanted by the law for killing a clerk, Otto Ludovisi, during a robbery at Thomas Scott’s store in Sunol, California, on January 10, 1871. Just prior to his fatal encounter with Sheriff Harry Morse, Soto had butchered a beef for a planned fiesta. He then rode from Juan Alvarado’s adobe to Juan Lopez’s house to borrow salt and onions for his barbecue; that is where the sheriff discovered Soto.

Morse found out that Bartolo Sepulveda might have been the second fleeing bandido who exchanged coats with Soto. Sepulveda escaped then, but ended up convicted for helping Soto kill the store clerk. California Gov. George Stoneman believed Sepulveda was innocent of the murder and pardoned him in 1885.

After his gunfight with Soto, Sheriff Morse became the West Coast’s most famous manhunter. In the next two decades, he brought down a corralful of desperadoes, including America’s most notorious stage robber—Black Bart, credited with 29 holdups. Morse’s law enforcement career spanned five decades. He died peacefully in bed and left a $100,000 estate to his heirs.

Recommended: Lawman: The Life & Times of Harry Morse, 1835-1912 by John Boessenecker, published by University of Oklahoma Press.