Travel across Arkansas, Oklahoma and Colorado and discover the real and imagined locations of the iconic novel and 1969 film’s locations.

All Images by Johnny D. Boggs Unless Otherwise Noted

People do not give it credence that a freelance writer would leave home on an assignment for a Western history magazine to follow the trail of a 14-year-old girl’s quest for justice—since that girl, and her one-eyed deputy marshal friend, never really existed except in Charles Portis’s imagination.

I will say this to travel writers: It does not happen every day.

While Arkansas has its own True Grit Trail (Arkansas 22 from Dardanelle to Fort Smith) and four Dardanelle high school students came up with a route to Oklahoma’s Winding Stair Mountains for the Yell County Historical Society, I follow Rand McNally, Mattie Ross and Paramount Pictures.

And discover how much Portis got right.

In 1968, Simon & Schuster published True Grit, the 34-year-old ex-Arkansas newspaper journalist’s second novel. Reviews were spectacular: “a small masterpiece of American humor” (Memphis, Tennessee’s Commercial Appeal); “a new kind of Western, a horse opera with a difference” (Newsday); “as touching as it is irreverently amusing” (New York Times); and “speaks to every American who can read” (Washington Post).

In the novel, 14-year-old Mattie Ross’s father is murdered in Fort Smith by hired hand Tom Chaney (“There is trash for you,” Mattie says). Mattie and Yarnell Poindexter, a Black hired hand, leave the Rosses’ 480-acre farm in Yell County by train from Dardanelle to Fort Smith. So let’s hit the trail.

Arkansas

Had they traveled “as the crow flies,” Mattie says, they would have passed Mount Nebo (“where we had a little summer house so Mama could get away from the mosquitoes”) and Mount Magazine, “the highest point in Arkansas.” (Yes, It’s 2,753 feet above sea level.)

Cabins, including many built by in the 1930s, are available for rent at Mount Nebo State Park, which offers views of the Arkansas River Valley. Nebo became popular as a resort in 1889 when the Summit Park Hotel opened. It was not popular, however, with Cherokees, Choctaws, Creeks, Seminoles and Chickasaws, who passed Nebo on their forced removal from the Southeast to present-day Oklahoma. Farther west, what’s now Mount Magazine State Park attracted French explorers and hunters in the 17th and 18th centuries and permanent settlers after the Civil War.

Fort Smith did not impress Mattie (“all the windows need washing”), but it has impressed many Western history buffs.

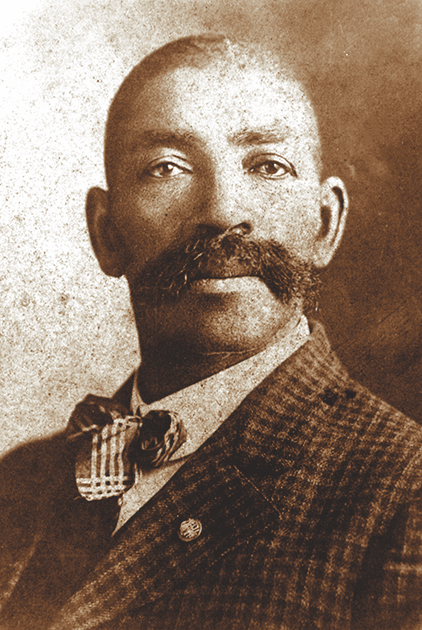

Established in 1872, the federal court for the Western District of Arkansas was first headquartered on the grounds of a military post, now part of Fort Smith National Historic Site. Barracks were turned into the courtroom (1875-89) for Judge Isaac Parker, who ruled the district from 1872 to 1896. The basement’s mess halls became the jail, aptly named “Hell on the Border.”

Mattie witnesses the hanging of three prisoners, performed by George Maledon, who dropped 60 of the 79— sometimes six at a time—during Parker’s reign. The gallows, now reconstructed, first went up in 1873, then were replaced in 1886.

Mattie hires drunken, one-eyed Deputy Marshal Reuben J. “Rooster” Cogburn to go after Chaney for a reward. That won’t be easy because Chaney is riding with Lucky Ned Pepper’s train-robbing gang. A Texas Ranger named LaBeouf, seeking Chaney for another murder, joins up. They ferry across the Arkansas River and enter Indian Territory on the Fort Gibson Road – “if you could call it a road.”

Wide Spot in the Road: Arkansas

Hot Springs National Park

This 5,500-acre park within the Hot Springs city limits features eight historic bathhouses on Bathhouse Row, but there’s more than just geothermal spring water to this town. For True Grit fans, Rooster Cogburn rode with Frank James and Cole Younger, and in 1874 the James-Younger Gang robbed a stagecoach bound for Hot Springs from Malvern, about 20 miles southeast. “All the coach passengers were robbed,” Charles Portis wrote for The Atlantic in 1999. “One, a G.R. Crump, of Memphis, got his watch and money back when Cole Younger learned that he had been a Confederate soldier—or so one story has it.” In 1969, True Grit’s world premiere in Little Rock was a Democratic fundraiser, and Portis objected to such politicizing. The next day, Portis rented a theater in Hot Springs for his own premiere. Arkansas native Glen Campbell attended the Little Rock shindig. Portis got a standing ovation at Hot Springs, where proceeds went to the Arkansas Children’s Colony. HotSprings.org

Good Eats & Sleeps:

Eats: Bricktown Brewery, Fort Smith, AR

Sleeps: Beland Manor Bed & Breakfast,

Fort Smith, AR

Oklahoma

Mattie wasn’t the only person who complained about the 208-mile road from Little Rock to Fort Gibson. Vinita’s Weekly Chieftain opined in 1888 that “to call the Fort Gibson road a stage road is a misnomer. The roads of our nation are but a standing shame and disgrace….”

The posse skirts through the San Bois Mountains (check out Robbers Cave State Park north of Wilburton) and captures Emmett Quincey and Moon, unfortunately for those soon-dead outlaws, while Pepper’s boys are robbing the Katy “Flyer” at Wagoner’s Switch. Wagoner (Wagoner City Historical Museum) started where the Katy—aka Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railway—and Kansas and Arkansas Valley Railway’s tracks crossed. The “Flyer,” however, didn’t start running until 1893, rushing travelers to Chicago’s “world’s fair.”

Our heroes travel on to “McAlester’s Store on the M.K. and T. Railroad Tracks.” In what’s now McAlester, James J. McAlester opened a store in 1869 on the Texas Road before the Katy ran a line nearby in 1872. By 1886, Muskogee’s Indian Record called McAlester’s “doubtless the largest store building in the Indian Territory.”

From McAlester’s, the trio turns east for the Winding Stair Mountains, where today the Talimena National Scenic Byway runs 54 miles from Talihina, Oklahoma, to Mena, Arkansas. Justice/revenge comes in Homeric fashion, La Boeuf gets a headache, and Cogburn saves Mattie’s life, though her right arm is amputated.

Wide Spot in the Road: Oklahoma

Federal deputy marshals did not provide all the law in Indian Territory in the 1800s. Tribes had their own courts, and on state Highway 3 near Ringold, Oklahoma, a historical marker salutes the Alikchi Court Ground, which served the Choctaw Nation’s Apukshunnubbee District from 1838 until 1906. The last legal execution under tribal law was carried out there on July 13, 1899, when Sheriff Tom Watson shot to death convicted murderer William Goings. Goings said he was innocent till the very end. The Oklahoma Historical Market erected the marker in 1995. VisitMcCurtainCounty.com

Good Eats & Sleeps:

Eats: What About Bob’s Restaurant, McAlester, OK

Sleeps: Hootie Creek Guest House, Talihina, OK

Epilogue

In the final pages, Mattie travels to Memphis, Tennessee, in 1903, hoping to see Rooster, who is appearing in a Wild West show headlined by Cole Younger and Frank James. Alas, she learns that Rooster died in Jonesboro, Arkansas, a few days earlier.

On May 13, 1903, in Jonesboro (Arkansas State University Museum), “fully 10,000 people” caught the Cole Younger and Frank James Historical Wild West for two performances. “It was pronounced generally as a ‘fake,” a newspaper correspondent observed, “and an imposition upon the people.” The troupe hit Memphis on May 25, where, the Commercial Appeal noted, spectators “got over the disappointment in not seeing Frank James and Cole Younger hold up a train or blow a safe.”

Mattie reburies Rooster on the family plot near Dardanelle (Lake Dardanelle State Park), where Mattie’s adventure begins and ends.

The 1969 Film’s Trail

“True Grit is good enough for me, it is good enough for you,” Charles Elliott wrote for Life magazine in 1968, “and if it isn’t good enough for some movie company then the free enterprise system really is going to hell.”

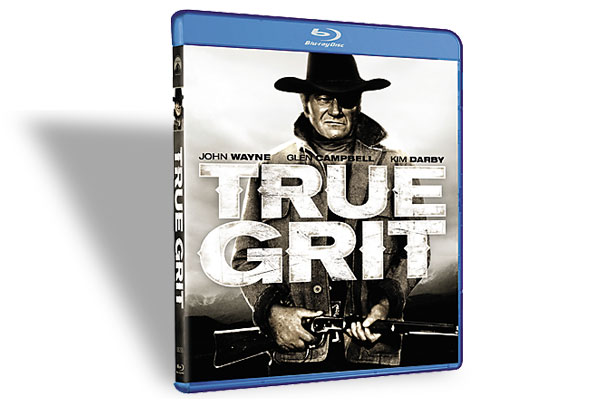

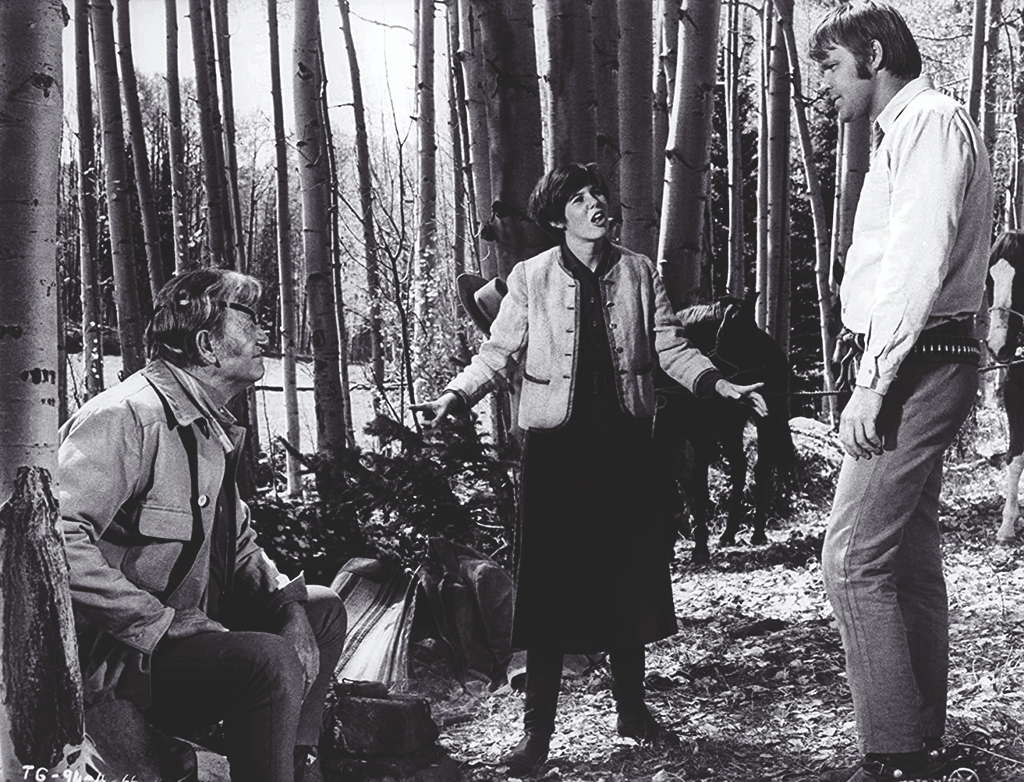

Free enterprise was fine. Portis reportedly earned $300,000 for movie rights. Directed by Henry Hathaway from a screenplay by Marguerite Roberts—blacklisted in 1951 for refusing to cooperate with the House Un-American Activities Committee—True Grit was released in 1969 and won John Wayne, as Rooster, his only Academy Award. Kim Darby played Mattie, and Glen Campbell tried to play La Boeuf. Instead of Arkansas-Oklahoma, the production headed to Colorado’s Rockies for location filming, even though, as The Ouray County Herald reported, “this region doesn’t resemble either Arkansas or Oklahoma.”

Set construction began in August 1968, with principal photography starting the following month.

“Signs at one of the more centrally located motels said, ‘Welcome, Paramount Pictures,’” Nancy Sparks wrote for The Wichita (Kansas) Eagle in October 1968. “The sign at our motel said, ‘Background music, shuffleboard, and dial telephones.’ Clearly it wasn’t John Wayne’s headquarters.”

The livery stable and gallows went up at Ridgway’s Hartwell Park, while across Lena Street a courthouse façade was erected, and buildings were turned into a saloon and grocery. The jail wagon that brings in Rooster’s prisoners is displayed at the Ouray County Ranch History Museum, formerly a railroad depot. Other film sites are in town. Visit Ridgway’s Visitors Center for details.

Outside of Ridgway, the Ross place is off Last Dollar Road, the ruins of McAlester’s store on County Road 60X, and you can recognize the site of Rooster’s shootout with Ned Pepper’s bunch at Debbie’s Meadow near Owl Creek Pass’s summit.

For the actual courthouse exteriors and the interior staircase where Mattie accosts Rooster, drive to Ouray (Ouray County Museum). The courthouse is at Fourth Street and Sixth Avenue. The snake pit that almost dooms Mattie is on private property off Camp Bird Road, while the ferry scenes are underwater at Blue Mesa Reservoir between Montrose and Gunnison.

You don’t have to be a True Grit fan, however, to appreciate this area’s history.

This ends my true account of how I followed a fictional trail—actually, two trails—when regular unleaded was $2.79 a gallon.

Wide Spot in the Road: Colorado

DURANGO & SILVERTON NARROW GAUGE RAILROAD

Before True Grit crews arrived in 1968, Colorado had recently been visited by another movie production—for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. The Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad was used for train-robbery scenes. The railroad linked the two towns in 1882, but Hollywood arrived after the mining heyday for films including 1950’s Ticket to Tomahawk, 1952’s Denver & Rio Grande (in which two locomotives collide head-on, not CGI) and 1957’s Night Passage (1957). Locomotives from the 1920s continue to pull rolling stock today for tourists. Overnight packages are available with accommodations at Silverton’s Grand Imperial Hotel. DurangoTrain.com

Good Eats & Sleeps:

Eats: True Grit Café, Ridgway, CO

Sleeps: Beaumont Hotel & Spa, Ouray, CO

Johnny D. Boggs is a longtime admirer of Charles Portis’s True Grit, but he thinks Norwood and The Dog of the South are funnier.