Preserving Polygamy became a women’s campaign in the late 1800s—a point that will surprise many, who assumed women hated the plural-wife dictate of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. And while there were many who did speak out strongly against the practice—Church founder Joseph Smith’s first wife, Emma Hale Smith; Brigham Young’s 19thwife, Ann Eliza Webb, who divorced him and traveled the nation decrying polygamy—there were also thousands of Mormon women who rallied, wrote and organized to fight for the right of their church to practice plural-marriage.

The crushing blow to polygamy was the Edmund-Tucker Act of 1887—the fourth time the federal government had tried to get rid of plural marriages. But this act went so much farther. It dissolved the corporation of the church and confiscated its properties and money. It required an anti-polygamy oath for prospective voters, jurors and public officials. It annulled territorial laws allowing illegitimate children to inherit. It required civil marriage licenses. It abrogated the common law spousal privilege for polygamists, therefore requiring wives to testify against their husbands, who faced a fine up to $800 and five years imprisonment on conviction of polygamy. It disenfranchised women, who had been given the vote by the Territorial Legislature in 1870. It replaced local judges with federally-appointed ones, and it prohibited Mormons from teaching in public schools.

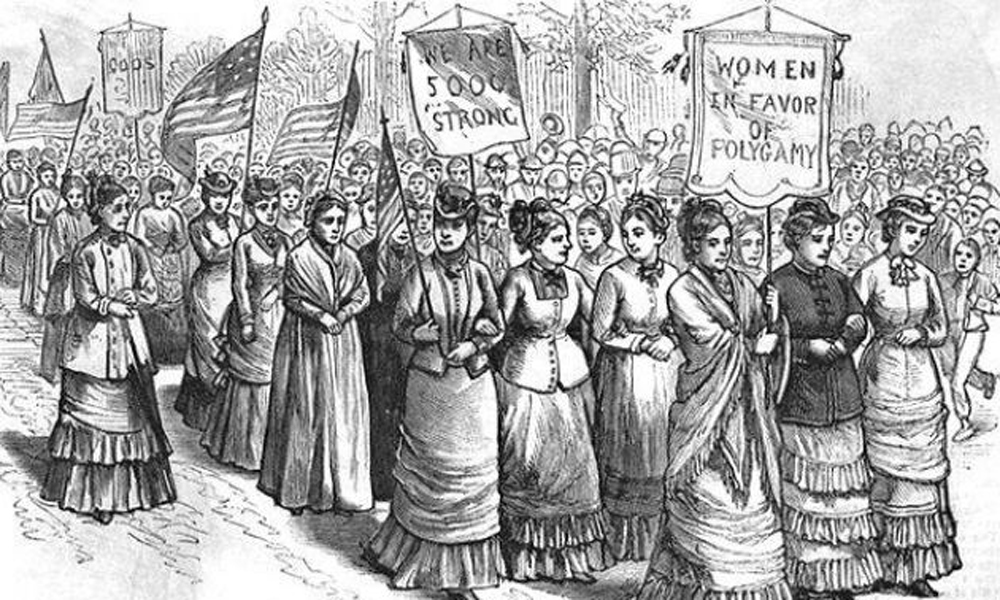

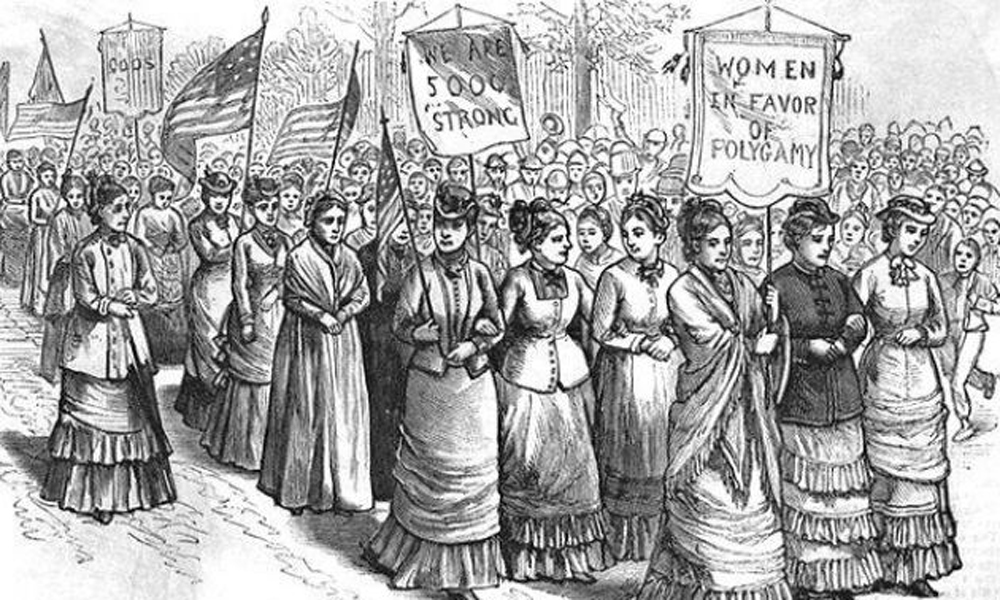

Mormon women actively and vociferously fought the Edmund-Tucker Act. While it was being debated—and a year before President Grover Cleveland signed it into law–two thousand Mormon women gathered at the Salt Lake Theater to protest the “indignities and insults heaped upon them as wives and daughters of Mormons in Utah district courts.”

The March 6, 1886 protest meeting chose Mary Isabella Horne as its leader. Thirty-three women presented personal statements against the act. Subsequently, the women compiled the proceedings into a 91-page pamphlet, “Mormon Women’s Protest: An Appeal for Freedom, Justice and Equal Rights,” that was distributed in the nation’s capital. The pamphlet contained the speeches, resolutions and poems of female doctors, teachers, authors, poets, women’s rights advocates, religious and community leaders, and mothers.

Among the patriotic voices at the protest was Mrs. H.C. Brown who stated: “We are here, not as Latter-day Saints, but as American citizens—members of that great commonwealth which our noble grandsires found and bled to establish—legal heirs to those rights and privileges bequeathed to that heaven-inspired document—the Constitution of the United States. Yes, legal heirs, yet illegally, unconstitutionally deprived of that dearest, most cherished of all.”

Church history suggests that Mormon women were politicized, in part, because of polygamy. As a church website notes: “Due to shared domestic responsibilities and the combined efforts of ‘sister wives’, women built and managed cooperative stores and a local silk industry, maintained a grain storage program, established welfare and home industry, edited a major women’s newspaper, attended medical school and developed a women’s hospital with community nurse and midwife training, led women’s suffrage efforts, and participated in public education and higher education.”

Church President Wilford Woodruff officially abolished plural marriages in 1890. By then, gaining statehood was the quest and only by getting rid of polygamy would Utah even be considered. Utah became the nation’s 45th state on January 4, 1896. And upon admission to the union, its women were again given the right to vote.