— Courtesy Xerxes 2004 at English Wikipedia —

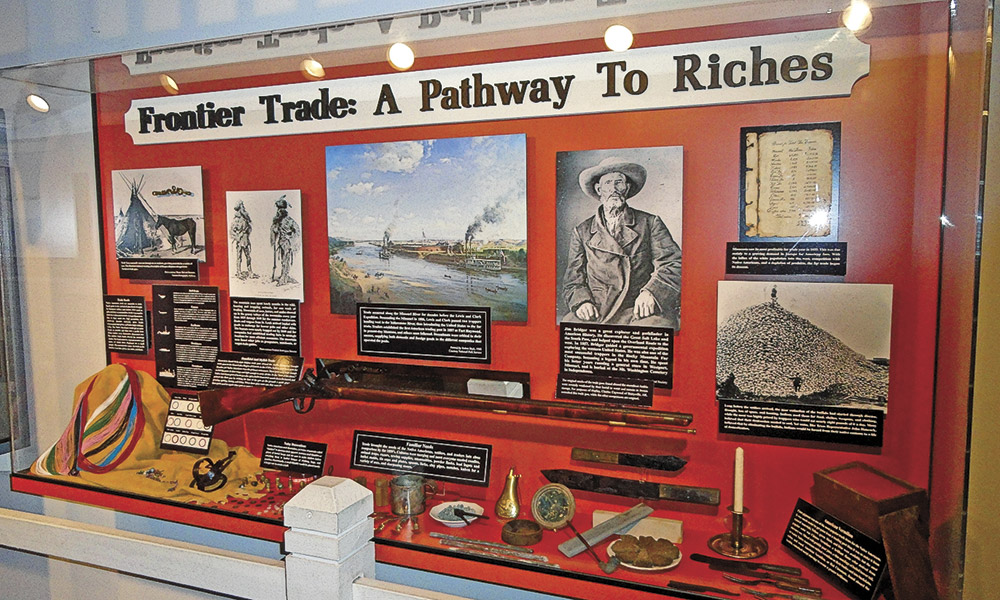

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark took their Corps of Discovery expedition up the Missouri River using keelboats and pirogues that they poled and propelled by dragging the vessels using heavy ropes. Following them, the fur traders also used those labor-intensive methods of transportation to haul trade goods upriver, and bring furs and pelts back down the Missouri to markets.

In 1819 the steamboat Independence departed from St. Louis and steamed upriver to the area of the Chariton River. This was the beginning of steamboat travel on the Missouri River. The Western Engineer would take nearly three months to steam from St. Louis to the confluence of the Yellowstone River near Fort Union in North Dakota.

Steam-powered boats became the primary vehicles for commercial transportation. These faster, bigger paddle-steamers revolutionized travel on the river and carried both supplies and passengers.

— Courtesy Kansas City Tourism —

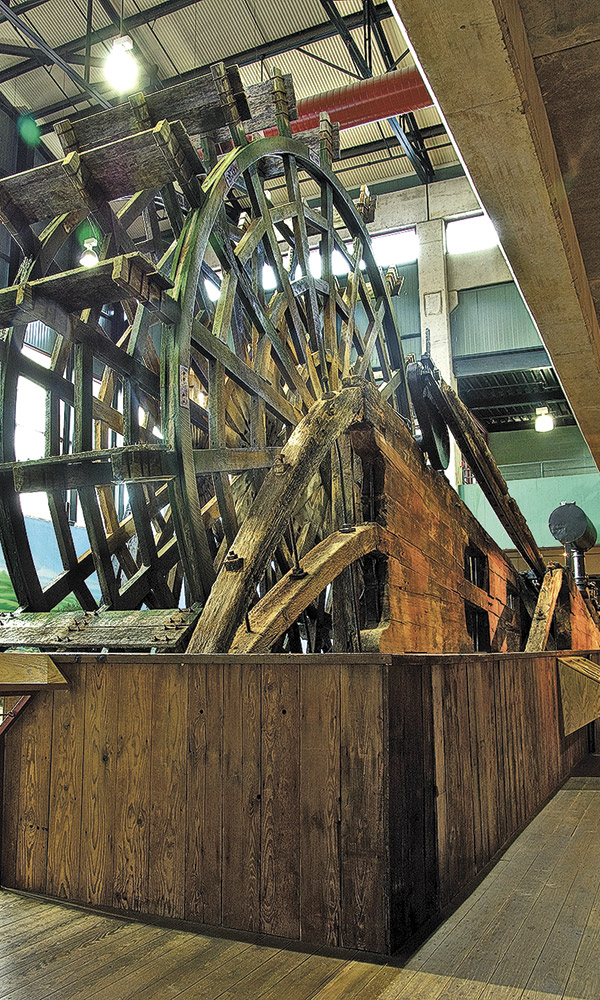

The best place to start a trip that highlights steamboat travel on the Missouri River is in Kansas City, not far from where in 1987 a group of five men located the wreck of the steamboat Arabia in a Kansas field, fully a half-mile from where the Missouri then flowed. They dug it up, recovering a large proportion of the more than 200 tons of cargo that had been aboard, bound for the frontier. In the years since, they have cleaned, restored and preserved the cargo. Some of the items are now on display at the Steamboat Arabia Museum in Kansas City, looking ready for use, even though they are more than 150 years old.

The Arabia, a 171-foot side-wheel steamer built in 1853, headed upstream from St. Louis on August 30, 1856. The steamer docked at Westport Landing (in present-day Kansas City) six days later, but soon slid back into the river to continue toward St. Joseph, Missouri, intending to go on to Council Bluffs and Sioux City, Iowa.

— Photo of Exhibit at Arabia Steamboat Museum Exhibit Courtesy Kansas City Tourism —

The cargo on the Arabia—ranging from heavy tools, harness and leather shoes, to fine china, perfume, beads and buttons—represented the best frontier goods to be had. And there were kegs of whiskey aboard. Just upstream from Westport Landing, the Arabia hit a sunken tree snag that rammed the hull and sent the steamboat to the bottom of the river. One mule died in the sinking, and all the cargo was lost, though the captain and crew survived.

When the wreck was rediscovered and then recovered in the late 1980s, the cargo was still aboard—except for the whiskey! Visiting the Steamboat Arabia Museum is like stepping back in time. In addition to displaying cargo items, the museum has a piece of the hull and the snag that brought the boat down. You can even watch and talk with conservators who continue to preserve the cargo from the Arabia.

From Kansas City, I head north along the Missouri for a stop in St. Joseph. Best known for its Pony Express roots, St. Joe has 13 museums and beautiful historical archi-

tecture. One interesting location to visit is Robidoux Row, which includes a museum dedicated to fur trader Joseph Robidoux, who built the structure in the 1850s.

— Courtesy BLM.gov —

Brownville, Nebraska, established in 1854 was a regular stopping point for steamboat traffic on the Missouri. Today visitors see the Meriwether Lewis Dredge and Museum of Missouri River History, take a stroll through the town, and visit the historic Carson House, once owned by Brownville founder Richard Brown.

Desoto National Wildlife Refuge in both Nebraska and Iowa, north of Omaha, is a great place to observe a vast population of seasonal waterfowl and wildlife. Here you can see another collection of steamboat cargo that once was bound for the frontier. The steamboat Bertrand left St. Louis for Montana but struck a submerged log on April 1, 1865, and quickly sank into the Missouri.

While a portion of the Bertrand’s cargo was immediately recovered, far more went down and stayed submerged until rediscovered in 1958 by modern-day treasure-hunters Sam Corbino and Jesse Pursell. They recovered items including bolts of cloth, food, clothing and tools. The mud of the Missouri had successfully encapsulated the goods, keeping them surprisingly intact until their recovery. A portion of the recovered cargo is now on display at the Desoto National Wildlife Refuge Visitor Center.

— Courtesy Jerrye and Roy Klotz, MD, Wikimedia Commons —

If I were on a steamboat, I’d stoke up the fire in the boiler and make some good time following the river through the Missouri National Recreational River area, continuing on to Pierre and then Bismarck, North Dakota, before steaming to Fort Union, an early fur trade post now operated as a National Historic Site. Each of these locations has attractions ranging from the natural landscape, to places important to the American Indian tribes of the region, and later the fur traders and frontier soldiers. Once in Montana, it is time to head west toward my ultimate destination: Fort Benton.

The first steamboat reached Fort Benton in 1860. The goods brought by steamboat up the Missouri from St. Louis were unloaded at Fort Benton and were dispersed throughout Montana Territory for use in gold camps and frontier towns.

After passing up the Missouri en route to Oregon in 1805, Meriwether Lewis launched his canoe back to St. Louis in 1806 from the area that would become Fort Benton. When fur trappers and traders used the area, they launched bullboats or keelboats, and after the first steamboat arrived, Fort Benton’s levee saw ever-increasing use.

A tour along the levee at Fort Benton today includes monuments to Lewis and Clark, Sacajawea and Thomas Francis Meagher. Old Fort Benton, the Museum of the Upper Missouri and the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument provide interpretation about all eras of Fort Benton’s history.

Side Roads

The Route

Kansas City, Missouri, north on I-29 to St. Joseph, MO, Brownville, NE, Bellevue, NE, and Desoto National Wildlife Refuge, IA & NE; Missouri National Recreational River, then Sioux Falls, SD; turn west on I-90 to Pierre, SD, then US 83/Highway 1804 north to Bismarck, ND; then northwest to Williston, ND, then west to Fort Union Trading Post National Historic Site, then US 2 to Fort Benton, MT

Places to Visit

Steamboat Arabia Museum, Kansas City, MO; Robidoux Row Museum, St. Joseph, MO; Meriwether Lewis Dredge Museum of Missouri River History, Brownville, NE; DeSoto National Wildlife Refuge, Bellevue, NE; South Dakota Cultural Heritage Center, Pierre, SD; Lewis and Clark Riverboat, Bismarck, ND; North Dakota Heritage Center and State Museum, Bismarck, ND; Fort Union Trading Post National Historic Site, Williston, ND; Old Fort Benton, Fort Benton, MT

Good Eats and Sleeps

Pierpont’s at Union Station, Kansas City, MO; InterContinental Kansas City at the Plaza, Kansas City, MO; Stoney Creek Hotel and Conference Center, St. Joseph, MO; Cattlemen’s Club Steakhouse, Pierre, SD; Blarney Stone Pub, Bismarck, ND;

Grand Union Hotel, Fort Benton, MT

Good Books

Wild Rivers, Wooden Boats by Michael Gillespie; Steamboat Treasure by Dorothy Heckmann Shrader

Road warrior Candy Moulton lives and writes in Encampment, Wyoming, or anywhere else she can find a place to open the laptop and work.