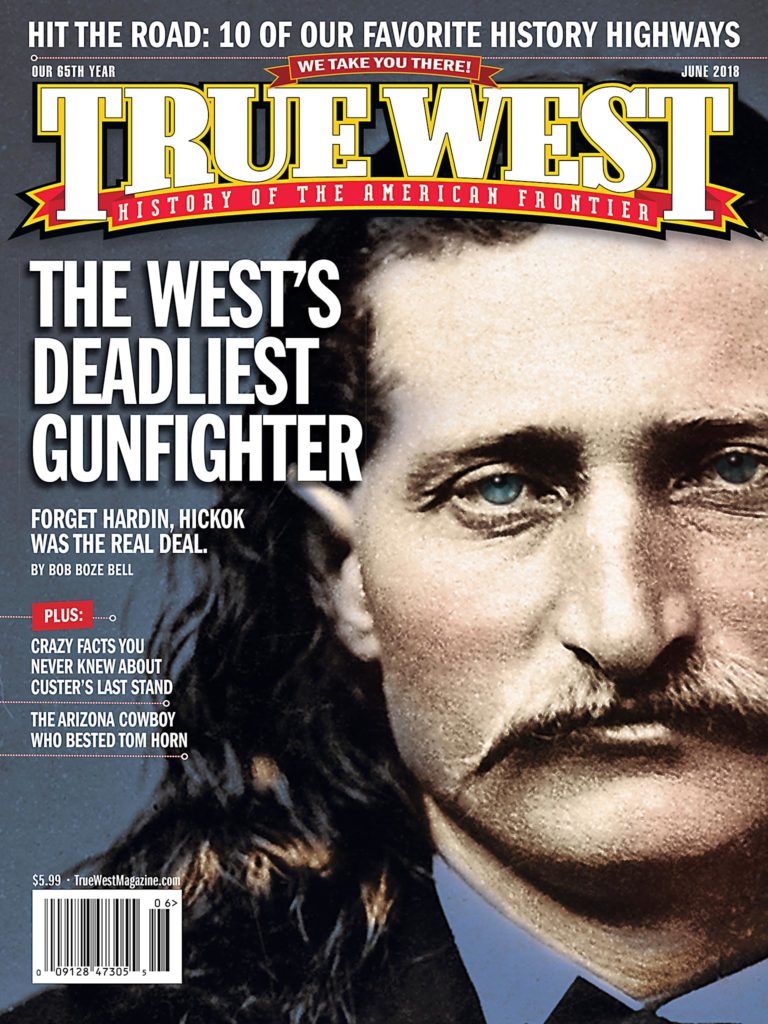

Like most Old West icons, gunfighter “Wild Bill” Hickok is shrouded in myths. He likely started many of them.

A teller of tall windies, he was quoted as saying, “I would be willing to take my oath on the Bible that I have killed over a hundred, a long ways off.”

After he told a particularly impossible adventure, someone would invariably ask him, “But Bill, how did you escape?”

A poker-faced Hickok replied, “I didn’t. I was killed.”

While researching my latest book, The Illustrated Life and Times of Wild Bill Hickok, I tackled these big myths:

— All illustrations by Bob Boze Bell unless otherwise noted —

The One and only “Wild Bill”

More than 30 frontiersmen went by the nickname “Wild Bill,” and Hickok had other nicknames besides “Wild Bill,” including “Dutch Bill,” “Duck Bill” and “Shanghai Bill.” Not bad for a guy named James. Yes, his name wasn’t Bill or even William. Still, evidence shows he used William at an early date (see timeline on the opposite page).

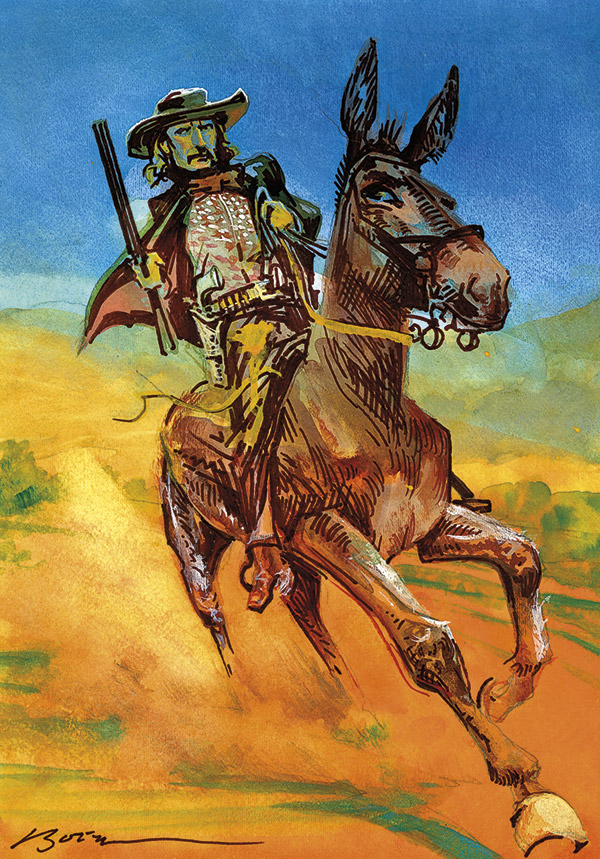

Hickok the Horseman

Yes, Hickok supposedly had a magical horse (Black Nell), but he usually preferred to ride a mule.

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

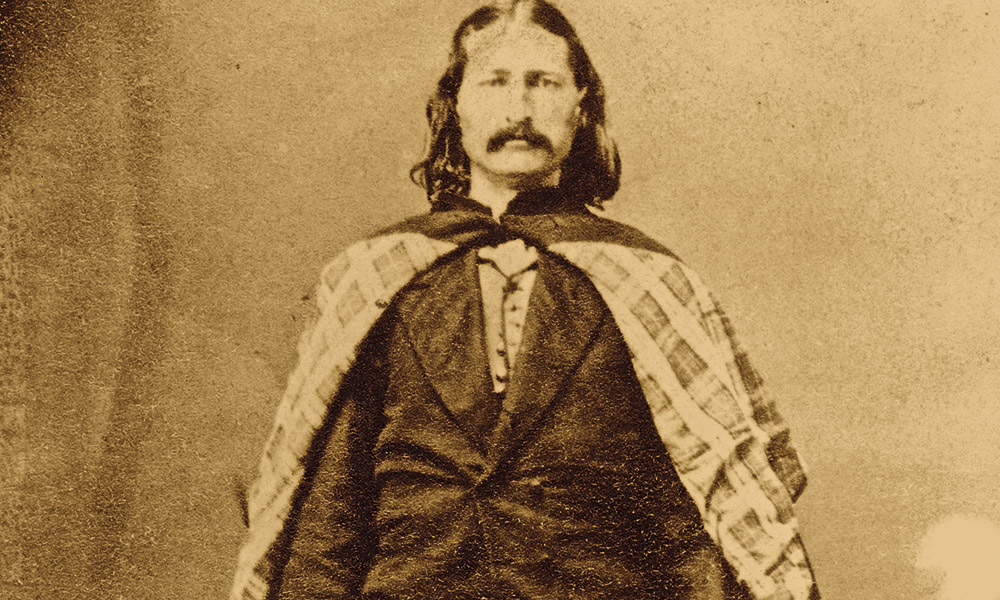

Wild Bill Wore His Hair Long Because He Was Effeminate

A prominent historian, in the 1960s, claimed Hickok was gay because of his long hair. This says more about the 1960s than the 1860s. Like many of the frontiersmen and scouts, Hickok wore his hair long in defiance to his enemies. It was a dare to his American Indian opponents to come and try and take it. He lived by the popular maxim, “A short haired man is looked upon as a coward.”

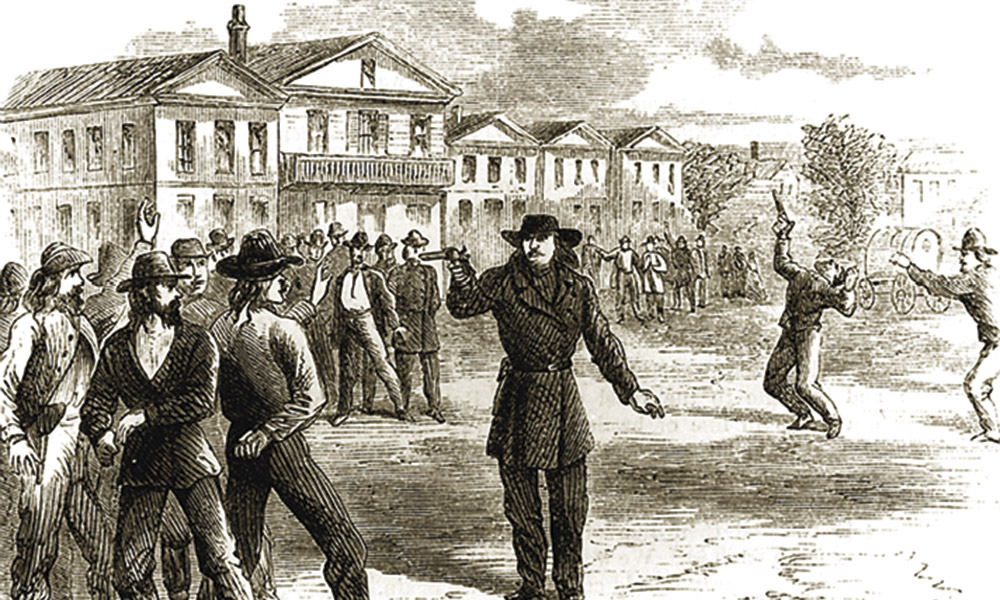

Face-to-Face Gunfights

Every classic Western movie showdown owes its genesis to one event: The Springfield, Missouri, gun battle between Hickok and Dave Tutt on July 21, 1865 (page 24). They faced off in the street, drew and fired. Only one survived. Cue the music.

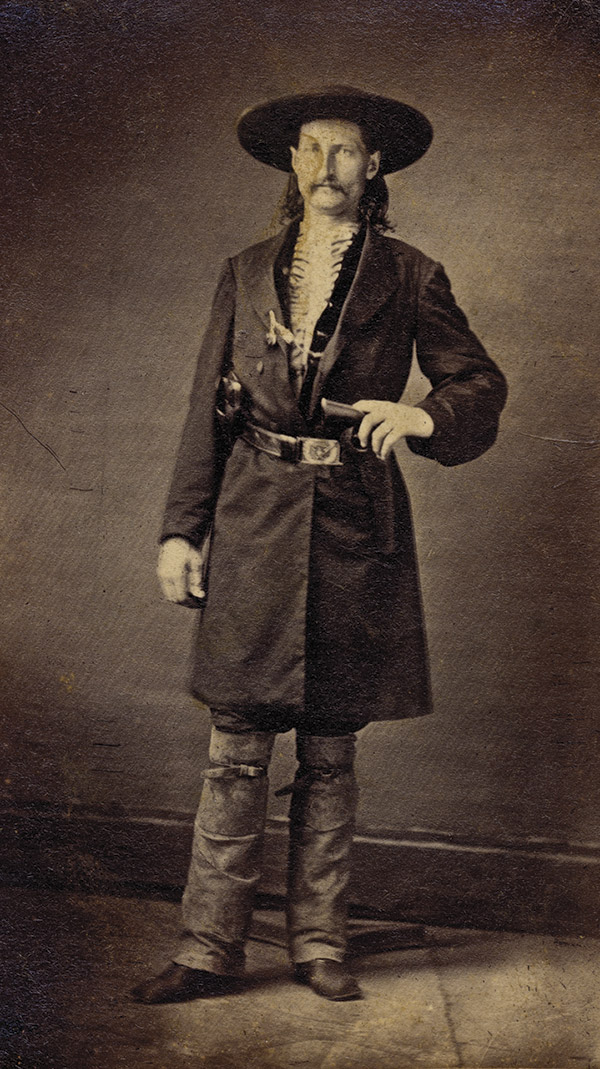

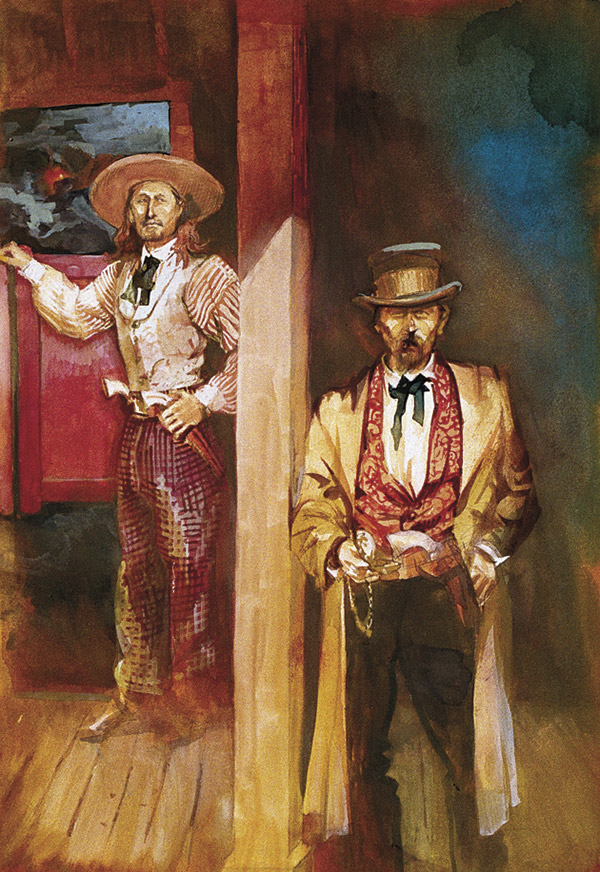

The Lady Killer

“Physically, he was a delight to look upon. Tall, lithe, and free in every motion, he rode and walked as if every muscle was perfection, and the careless swing of his body as he moved seemed perfectly in keeping with the man, the country, the time in which he lived.”

Okay, we get it, Libbie Custer. He looked like a stud. Anything else?

“I do not recall anything finer in the way of physical perfection than Wild Bill when he swung himself lightly from his saddle, and with graceful, swaying step, squarely set shoulders and well poised head…. He was rather fantastically clad, of course, but all that seemed perfectly in keeping with the time and place. He did not make an armory of his waist, but carried two pistols.”

Somebody throw some water on that woman! Husband George would not have been pleased.

The Town Tamer

Yes, Hickok, the man with the badge who kept the peace in Kansas cowtowns, created the image of the fearless lawman walking down the center of Main Street, eyes scanning the saloons for trouble. He was the first notorious peacekeeper; others, like Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson and Bill Tilghman, came later and were backdated into the myth by association.

Fast Draw Inventor

Yes, the fast draw originated with Wild Bill. As W.E. Webb stated, “His power lies in the wonderful quickness with which he draws a pistol and takes his aim.”

Blinded by VD?

In his last couple years, Hickok was going blind. Some eye experts believe he suffered from trachoma. But Hickok biographer Joseph G. Rosa suggested the gunfighter got a venereal disease from “brief affairs with the Cyprian sisterhood….” Syphilis can cause blindness.

The Deadly Conclusion

John Wesley Hardin is often mentioned as the deadliest gunfighter, having killed some 40 men. Never mind that many of these “kills” were merely assassinations, or worse—he once shot a man for snoring. Even though he claimed he got the drop on Hickok, no evidence supports this brag of his. In my estimation, Hardin was closer to Charles Manson than a bona fide gunfighter. The same can be said for other pretenders to the throne. Hickok was the first gunfighter—and the deadliest.

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

Let’s take a look at some of the highs and lows of Hickok’s epic life.

1858

The Mason Jar was invented.

February 1858

A grand dress ball took place in the evening for the residents of Monticello, Kansas Territory. William Hickok was a member of the committee of invitation. (This is convincing evidence that James was also known as William, or Bill, much earlier than the previously accepted 1862 date. Court records for this period also indicate he was referred to as both J.B. Hickok and William Hickok.)

Also this month, James filed a preemption claim for a quarter section (160 acres) of land where he has been squatting, off and on, for almost a year. He may have intended to claim and share this land with the rest of his family. Unfortunately, a Wyandot Indian named Samuel McCulloch held a prior claim to the same land and, under the provisions of an 1842 treaty, James’s claim was preempted.

Homeless and farmless, James moved to Olathe, where his cousin Guy Butler has a homestead.

— Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection —

March 22, 1858

James was elected village constable of Monticello Township, Johnson County, Kansas Territory.

1859

Oil was discovered in Titusville, Pennsylvania, launching a new era of lighting by kerosene.

Sometime in 1859

James allegedly met his hero Kit Carson during a trip to Santa Fe, New Mexico Territory. The present and future legends parted company as friends after a night of vigorous elbow-bending. (Rumor has it that Carson warned James about the perils of fraternizing with the ladies of the town, and James took the advice to heart.) No evidence confirms this meeting took place, but shortly before his death, James reportedly gave away a gun he said was a gift from his old pal, Kit Carson.

Another claim (made by William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody in his bio) has James staying with the Cody family in Leavenworth, Kansas, that autumn and winter. The Codys called their dwelling the “Big House” and intended to run it as a boarding house or hotel.

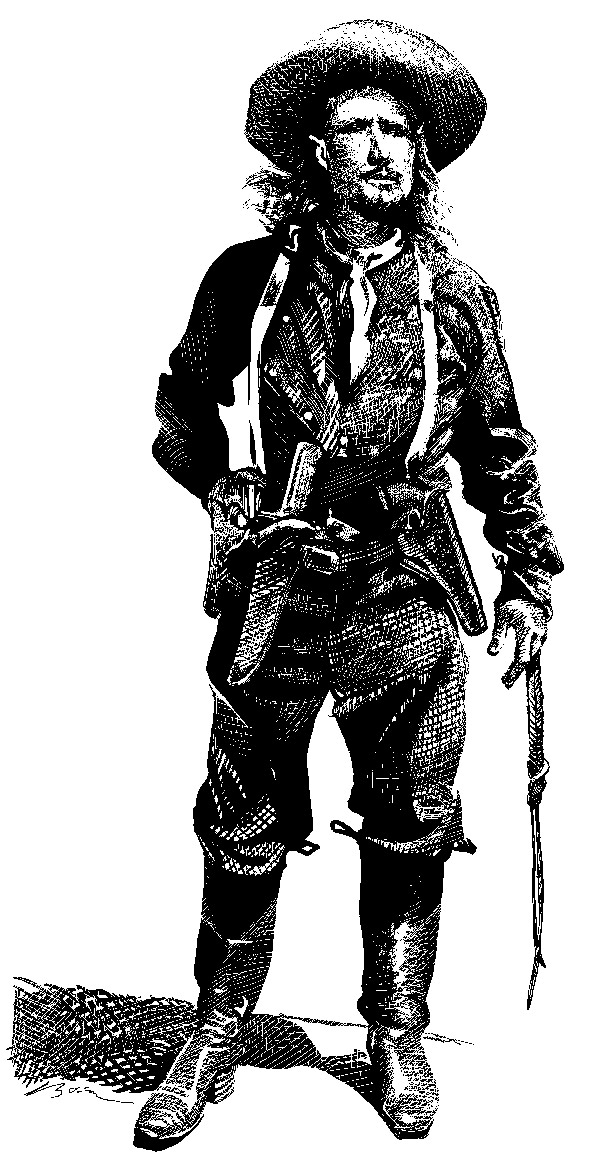

— Published in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, February 1867 —

1860

The Pony Express began. Abraham Lincoln was elected president.

April 3, 1860

James’s employer, Russell, Majors and Waddell, launched the Pony Express. James was allegedly too tall and heavy for riding duties, so he drove wagons and stagecoaches for the company.

September 1860

On one of his freight trips from Independence, Missouri, to Santa Fe, New Mexico Territory, James reportedly killed a bear in Raton Pass.

James also met the infamous Joseph Alfred “Jack” Slade, who was the line supervisor of the Pony Express company’s stagecoach division, at Sweetwater Bridge Station in Wyoming Territory.

At some point this month, Indians attacked one of the Pony Express relay stations—known as Plant’s Station— and drove off all the stock. James was elected to lead 40 stranded drivers on a quest to get the animals back. The trail led to the Powder River, on past Crazy Woman’s Fork to Clear Creek, where the trackers discovered the raider’s camp.

At James’s suggestion, the men waited until dark and then charged the encampment, shooting and shouting. The ensuing stampede of horses and inhabitants did the trick, and the men successfully recovered the stolen stock—and netted 100 Indian ponies to boot. This provided a great excuse for a party,

At Sweetwater Bridge Station, the James party celebrated the victory until the notorious Slade made an appearance and allegedly killed a stage driver after a drunken quarrel.

1861

Kansas became 34th state. Pony Express became obsolete after completion of transcontinental telegraph connected San Francisco and New York City.

1862

Early March 1862

James had been serving as wagon master in Missouri since October. When rebel forces attacked the wagon train, James escaped by leading a charge—straight through enemy ranks!

The next day, he headed for Independence to ask for help, but none was available. A Civil War was going on, after all!

With time on his hands, James added another notch to his legend. The story goes that a bartender chose the wrong side during a fight—and made the mistake of wounding an opponent. While the bartender was holed up in a building, an angry crowd, from the winning side, gathered outside for a friendly little necktie party. Hickok, with pistols drawn, planted himself between the mob and the bartender. His two shots in the air, followed by a threat to kill the first man who came forward, convinced the crowd to find less dangerous entertainment elsewhere. This may be when he earned his nickname, Wild Bill.

The next day, Hickok was finally able to enlist the aid of troopers and led them in pursuit of the wagon train, which they recaptured after a running battle. He found more men in Independence, and they helped the wagon train reach its destination safely.

— True West Archives —

March 7, 1862

Wild Bill used up three horses. A fourth was shot out from under him while he scouted advancing rebel troops.

March 8, 1862

During the Battle of Pea Ridge, Wild Bill got permission to place a band of sharpshooters (including himself) on a ridge to allow for a clear view of oncoming rebels. When a Confederate officer fell in the trenches, the sharpshooters believed James had killed enemy commander Gen. Ben McCulloch. Not true, however; McCulloch had been killed the day before, reportedly by Peter Pelican, of Company B, 36th Illinois Infantry.

Mid-March 1862

Wild Bill became a member of an elite group of Union spies who infiltrated enemy lines and reported their findings. He won many accolades for his work and allegedly ended up on Gen. Samuel R. Curtis’s staff as spy extraordinaire.

Wild Bill was among a band of scouts led by John R. Kelso on an excursion into Arkansas to track the enemy. They obtained Confederate uniforms along the way, which didn’t help much when they later stumbled into a rebel camp. After shooting their way out, they split up the next day to make their way back to Union lines as best they can.

Wild Bill traveled with Zeke Stone and John Allen, a “squaw man,” whose house was nearby. Allen’s wife agreed to help them escape. She also introduced Wild Bill and Stone to some Choctaw ladies. The scouts were, no doubt, appreciative of her kind introduction. Mrs. Allen also informed them of a Confederate captain who was expected to pass by with dispatches on the Wire Road the next day. He would be wearing a new uniform.

After the rest, the group came upon a farmhouse occupied by four rebels who were holding two white women hostage. Wild Bill, Stone and Allen stormed the cabin, taking the soldiers by surprise. One of the women, Susannah Moore, refused Wild Bill’s offer of help, saying she and her companion could fend for themselves.

Another band of Confederates showed up, but they too were taken unaware by Wild Bill and his compadres. The rebels panicked and scattered, with the scouts hot on their heels.

A rebel shot killed Wild Bill’s horse and landed him in a mud puddle. Moore rode up, cleaned him off and said she and the other woman could ride double, so Wild Bill could take her horse. Seeing that she could handle herself, Wild Bill gave her a pair of pistols and watched the women ride away.

The scouts then made their way safely back to headquarters, where they gave their information to Curtis.

1863

William Clarke Quantrill’s Raiders sacked and burned Lawrence, Kansas. The Battle of Gettysburg was fought. Perrier water was introduced in France.

Autumn 1863

Wild Bill became the proud owner of Black Nell, and another legend was born. He captured the mare after killing her rebel owner and a few of his companions during a fight in Missouri. He paid the U.S. government $225 for this prize of war.

Black Nell’s escapades were publicized by Col. George Ward Nichols, Wild Bill’s overly enthusiastic and highly imaginative biographer. One day, Wild Bill galloped into Springfield and signaled to his mount, who immediately stopped and fell to the ground. Leaving her in the street, Wild Bill walked into a saloon and bet that Black Nell could enter the saloon and climb on a billiard table. As Nichols told it, in the February 1867 issue of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine:

“Bill whistled in a low tone. Nell instantly scrambled to her feet, walked toward him, put her nose affectionately under his arm, followed him into the room, and to my extreme wonderment climbed upon the billiard-table, to the extreme astonishment of the table no doubt, for it groaned under the weight of the four-legged animal and several of those who were simple bifurcated, and whom Nell permitted to sit upon her.”

Black Nell’s equine exploits were debunked by the spoil-sport editor of The Missouri Weekly Patriot on January 31, 1867:

“The equestrian scenes given are purely imaginary. The extraordinary black mare, Nell, (which was in fact a black stallion, blind in the right eye, and a ‘goer,’) wouldn’t ‘fall as if struck by a cannon ball’ when Hickok ‘slowly waved his hand over her head with a circular motion’ worth a cent. And none of our citizens ever saw her (or him) ‘wink affirmatively’ to Bill’s mention of her (or his) great sagacity. Nor did she (or he) ever jump upon the billiard table of the Lyon House at ‘William’s low whistle….’”

1865

July 20, 1865

Trouble started between Wild Bill and Dave Tutt during a card game at a hotel on South Street in Springfield, Missouri. Tutt kept trying to pick a fight, but Wild Bill refused to rise to the bait, which only made Tutt angrier.

After a back and forth about a horse trade payment Tutt claimed Wild Bill owed him, Tutt grabbed Wild Bill’s watch, as collateral, and walked away.

These two had not been friendly. Wild Bill probably didn’t take kindly to Tutt’s involvement with Susannah Moore; he was getting even by taking up with Tutt’s sister.

One of Tutt’s buddies reportedly told Wild Bill that Tutt planned to flaunt the watch at the town square the next day. Wild Bill allegedly responded that “Tutt shouldn’t pack that watch across the [square] unless dead men could walk.”

July 27, 1865

Hickok’s Wild Bill nickname was published for the first time. Springfield’s Missouri Weekly Patriot announced that “David Tutt…was shot on the public square, at 6 o’clock P.M., on Friday last, by James B. Hickok, better known in Southwest Missouri as ‘Wild Bill.’ The difficulty occurred from a game of cards.”

1876

August 2, 1876

Wild Bill Hickok walked from his camp on the edge of Deadwood, Dakota Territory, to Nuttall & Mann’s Saloon. Entering around noon, he encountered about a half-dozen men. Three men were playing draw poker. Wild Bill recognized Missouri River steamboat captain William R. Massie and Charlie Henry Rich, a card dealer Wild Bill knew from his days in Cheyenne, Wyoming Territory. Wild Bill joined their game.

Wild Bill sat in the only available seat, near the rear entrance of the saloon, facing the front door. He usually sat along the west wall, but Rich was occupying that seat. Wild Bill preferred that seat’s view of the entire room, including good views of the front and back doors, and asked Rich for his “regular” seat, but the gambler refused to move.

Wild Bill, uncomfortable with the fact that his back was exposed to the open bar and rear door, once again asked Rich to trade places. This time, the other players chided Wild Bill, telling him he had nothing to worry about this early in the day. Wild Bill took the empty seat.

The four men had been playing draw poker for almost three hours when Jack McCall (also known as Bill Sutherland) walked through the front door, headed over to the bar, paused, moved down the bar and stopped momentarily at the scales sitting on the end of the bar.

Wild Bill threw down his hand in disgust and said, “The old duffer, he broke me on that hand.”

McCall stepped forward, took out a pistol and pointed it at the back of Wild Bill’s head, pulling the trigger at the same instant.

The bullet exited Wild Bill’s right cheek near the bottom of his nose. His head moved slightly forward, and he was still for a moment. Then he fell sideways off his stool onto the floor. He died instantly.

August 3, 1876

“Colorado Charlie” Utter held a funeral service for Wild Bill. Jack McCall was tried for murder and acquitted by an illegal miners’ court. Later on, he was legally tried in Yankton.

December 6, 1876

Jack McCall was convicted of murder and, on March 1, 1877, was hanged.

Wild Bill Still Looms Large

Did Wild Bill suffer from a dose of syphilis that led to eyesight issues? In my opinion, he probably did. Could he have hit a big strike in Deadwood and settled down with wife Agnes on a horse ranch? Probably not, but that was his dream.

Instead, he became something else: “Prince of the Pistoleers.” All the terms that followed: the “Showdown,” “Gun Man,” “Gunslinger” and, of course, “Gunfighter” came directly from him and his storied life. He was the first gunfighter. And his boast came true: he did things Kit Carson never dreamed of doing.

Bob Boze Bell’s “Wild Bill” Book Tour

Bob Boze Bell’s “Wild Bill” Book Tour

Author and illustrator Bob Boze Bell will launch his North American “Wild Bill” Book Tour on June 16 at the Adams Museum in Deadwood, South Dakota. At 11 a.m. he will speak about the long journey to bring Deadwood’s favorite son to life.

The “Prince of Pistoleers” meets the “Prince of Western History” in Bell’s much-anticipated, new book—chock-full of great art, rare photos, authoritative history and that unique dose of Bell whimsy that True West Magazine readers have come to expect. The book is a must-have addition to every Old West collection.

Adams Museum

11:00 a.m.–2:00 p.m.

Admission by donation

For more information: 605-722-4800