The silverwork is perfect, the turquoise is spectacular, so is the price tag, but after all, this was made by a Native American and will be a family treasure forever.

But is it a fake?

Is it really machine-made in the Philippines or slave-labor-made in China?

Besides, it’s a federal offense—has been for 87 years—to counterfeit Indian art in America. But that law has done little to stop the fraud.

That’s why the Council for Indigenous Arts and Crafts is an important help in fighting back.

“Imported and mass-produced Indian-style art is putting Native American artists out of business,” the Council warns on its website, noting that for thousands of Natives, their art is their livelihood.

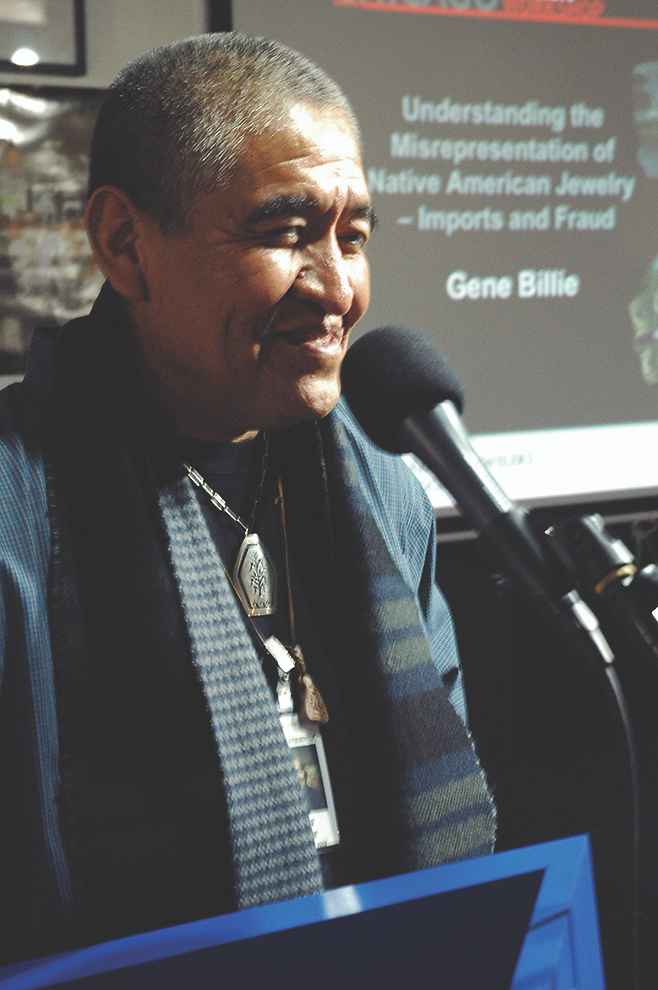

Council president Gene E. Billie of Albuquerque, New Mexico, explains:

“The fake market is worth millions, while the average Native artist from the reservation makes from $12,000 to $18,000 a year. The fakes and frauds have affected every Native artist, from the most successful to the beginner. And it discourages the young from learning the art because they have to compete with the fakes that undercut prices. Our council gives them a little bit of hope.”

The council was created in 1996 by Zuni artist Tony Eriacho and Pam Phillips, an Anglo woman long involved in helping Native artists. It became dormant for a time after Eriacho’s death in 2014, but then was reactivated by Billie and other board members from the Native Jewelers Society.

Before the pandemic, council board members—on their own dime—traveled to various art shows around the country to demonstrate the difference between authentic pieces and fakes and frauds. They’re gearing up again.

“We want to educate people on what to look for,” Billie notes. “How to tell the difference between a one-of-a-kind piece versus a machine-made fake; how to read hallmarks, and books to look up artists to be sure you’re dealing with a real Native American.”

The last point cuts to the quick: Some phonies pass themselves off as Native, either stealing names or making up identities.

Help also comes from federal law. In 1935, counterfeit Native art became illegal. Violators face up to five years in prison and $250,000 in fines. (Natives note that’s a “pittance” in the multimillion fake market.) The law’s been amended since, but Natives say it needs more teeth.

National Geographic spelled out the most extensive federal investigation into the fake industry in a March 2018 article titled: “Biggest Fake Native American Art Conspiracy Revealed.” It cited one criminal ring that imported $11.8 million in counterfeits from 2010 to 2015. In August 2018, the first dealer to be sentenced was Albuquerque dealer Nael Ali, who pled guilty to passing off Filipino fakes. He got six months and a fine of $9,048.78.

Will that deter a multimillion-dollar industry?

In the meantime, buyers need to protect themselves and help protect the Native artists they proudly collect, Billie says. That’s why it’s important to only buy Native art from juried shows or reputable dealers.

A list of upcoming juried shows can be found at NativeJewelersSociety.com.

Jana Bommersbach has earned recognition as Arizona’s Journalist of the Year and won an Emmy and two Lifetime Achievement Awards. She cowrote the Emmy-winning Outrageous Arizona and has written three true crime books,

a children’s book and the historical novel Cattle Kate.