A 1900 epidemic foreshadowed modern issues.

Stop us if you’ve heard this one before. An epidemic rears its ugly head. Federal and state officials are at loggerheads about its existence, let alone what to do about it. Leaders debate the economic impact of the disease and public health programs aimed at fighting it.

And all of this took place in the early part of the 20th century.

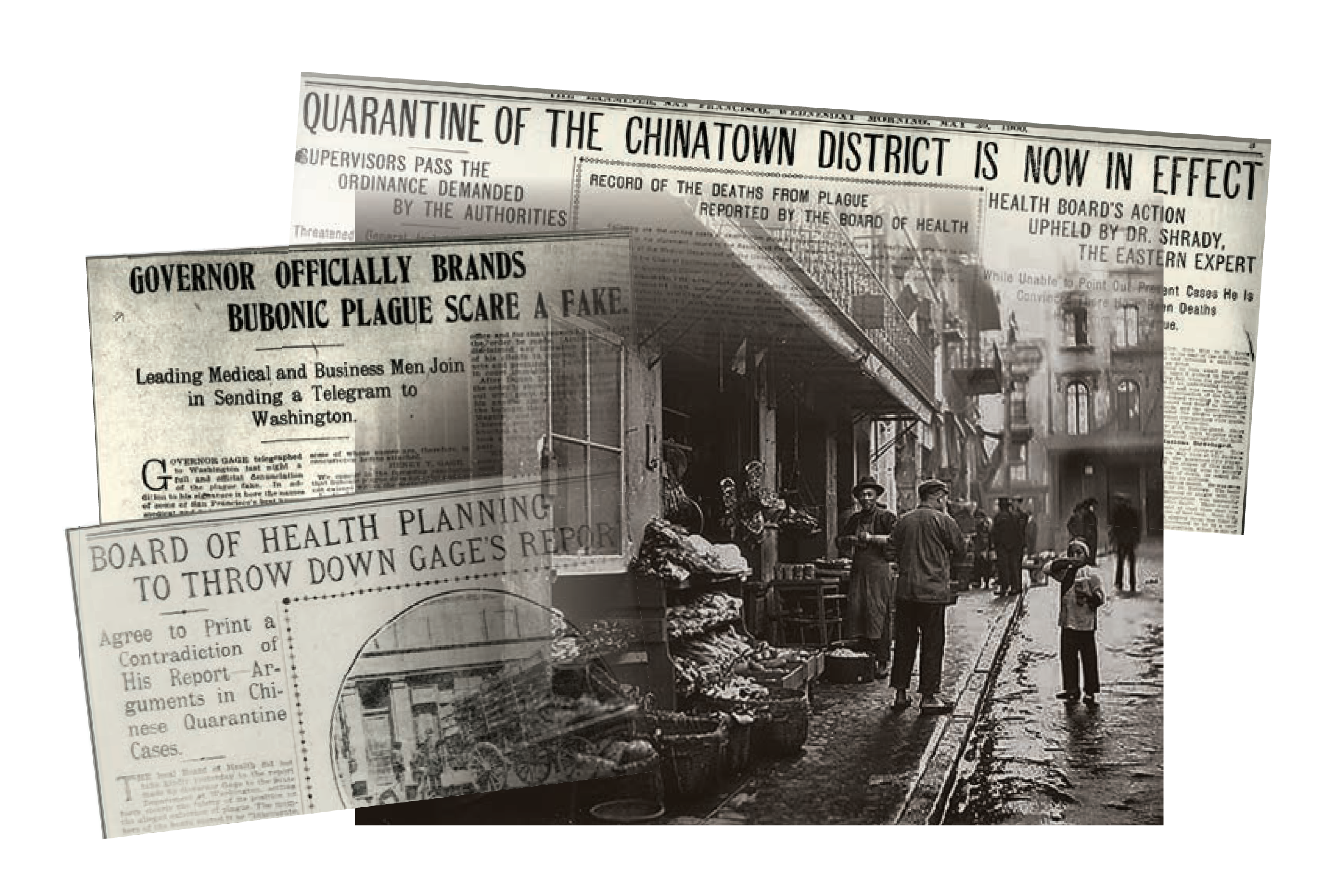

San Francisco was the locale, a major destination for Asian imports and immigrants. It’s not clear exactly what started things, but in early 1900, a resident of Chinatown was diagnosed with bubonic plague. He soon died. The news was shared with city public health officials as well as Joseph Kinyoun, the chief quarantine officer of the U.S. Marine Health Service (the forerunner of the federal public health service).

Kinyoun would champion the fight against the plague. He faced stiff opposition from California Governor Henry Gage. The Republican was closely allied with the business (especially the railroad) community. He denied that an outbreak existed, no matter what the evidence showed.

The feds tried quarantining Chinatown, but the residents took the case to court, saying it discriminated on the basis of race. A judge found in their favor (a rarity, considering the general racism against Chinese people at the time). Kinyoun then tried to implement mandatory vaccinations in that section of town. But the vaccine had never been tried on humans and was not approved, so that attempt failed as well.

For his part, Governor Gage tried to censor any media reports about the plague; the legislature didn’t support that. Several major newspapers did champion his cause, while others outside San Francisco took the opposite position. Lawmakers appropriated $100,000 so Gage could undertake a public relations campaign against Kinyoun and anyone else who dared say that an epidemic existed.

Meanwhile, Gage and federal officials reached some secret agreements aimed at taking low-key action to keep the plague under control while also keeping word of it under wraps. Both sides violated the agreements, which just made the situation worse. Cooperation between Washington and Sacramento seemed hopeless, especially as the rhetoric heated up.

In response, Washington officials appointed a three-person panel to look into the controversy. Its conclusive findings: that the plague was present in San Francisco and spreading. Governor Gage continued his public denials—but behind the scenes, he made another deal with President William McKinley. The committee report would be suppressed, yet city and state agencies would inspect and sanitize Chinatown, especially in buildings and spaces where the plague had been identified.

But word of the banned federal report still got out and was published in newspapers across the country. Several states, including Texas, Colorado and Louisiana passed their own quarantines on California, and others threatened to do the same. All of Governor Gage’s efforts had been aimed at protecting the state economy. They were now having the opposite effect.

Gage had become an embarrassment to his railroad baron patrons and they refused to support him for a second term in 1902. His successor implemented medical programs to deal with the situation, and the epidemic faded out by the end of 1904.

The federal public health system suffered. Publicity over the deal that suppressed the commission report proved highly damaging to its reputation; it wouldn’t recover until World War I.

And feelings against the Chinese stayed negative across the country. The general opinion was that they and their areas were bearers of sickness and death. If anything, racism toward the residents of Chinatown got even worse.

There were no winners in the San Francisco bubonic plague public health crisis of 1900-1904. And the actual victims of the outbreak—the 119 people who died—were largely forgotten outside the Bay Area Chinese community. And it doesn’t look like any lessons were learned by future generations.