— Courtesy G.W. Frank Museum of History and Culture —

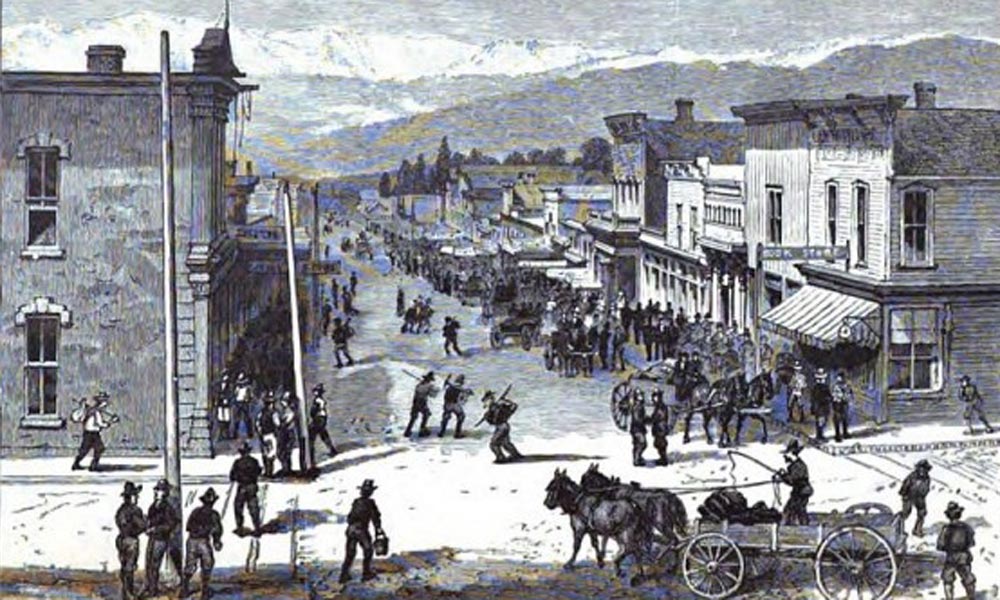

Splendiferous. That sums up the opulence of the 1890 G.W. Frank House in Kearney, Nebraska—the showplace of a man who promoted this piece of the American prairie, betting it would one day be the Great Electric City of the Plains.

George Washington Frank didn’t see the Cornhusker State as just ranchland and farmland. He envisioned a far more expansive future, wining and dining investors in the magnificent three-story, roughly 15,000-square-foot home designed by his architect son, George William, for him and his wife, Phoebe.

Guests were entertained on the first floor, with its tapestry rugs and intricately carved wood—on ceilings, fireplaces, doorways, stairways, wainscoting. A stained glass nymph with a bird graced the window at the top of the first floor landing.

As the first electric home in Kearney—and one of the first in the nation—crystal chandeliers lit most rooms. Every touch reinforced the notion that Kearney promised the kind of wealth that could afford such a home.

The proof of persuasion was the boom George Sr. brought to town. “We had a cotton mill in a place that doesn’t grow cotton, a paper mill in a place that doesn’t have trees,” notes William Stoutamire, director of the G.W. Frank Museum of History and Culture.

But alas, the panic and worldwide financial collapse of 1893 ruined everything, including the Frank family’s fortune. Their magnificent house was sold in 1907 to a couple who converted it to the Grothan Elmwood Sanitarian. When the couple divorced in 1911, the state of Nebraska bought the home to serve as the State Tuberculosis Hospital. In 1971, what’s now the University of Nebraska at Kearney purchased the house, which, two years later, earned a spot on the National Register of Historic Places. The splendiferous first floor opened as a museum in 1976, showing off the high-water mark of Kearney’s boom days.

But Stoutamire, who took over in 2014, is expanding that history—“rebranding the house,” as he puts it.

“Most people have seen the ‘neat old house’ and had no reason to return,” he says. “I needed to create a museum you want to come back to.”

He set out to tell the entire story of the house, including the much more modest second floor and completely unadorned third floor. It’s a story of elaborate wealth and poverty-stricken patients; of prejudice and controversy, as people of different races were mingled to the consternation of some.

“This is a living building,” he says. “So many want to tell just the family story, but I want to tell all the stories.”

He’s overseeing a complete renovation, with the help of graduate students, confident the new museum will draw visitors for decades to come.

Jana Bommersbach has earned recognition as Arizona’s Journalist of the Year and won an Emmy and two Lifetime Achievement Awards. She co wrote the Emmy-winning Outrageous Arizona and has written two true crime books, a children’s book and the historical novel Cattle Kate.