Discover the life of the legendary Comanche following the arrows in the Lone Star State.

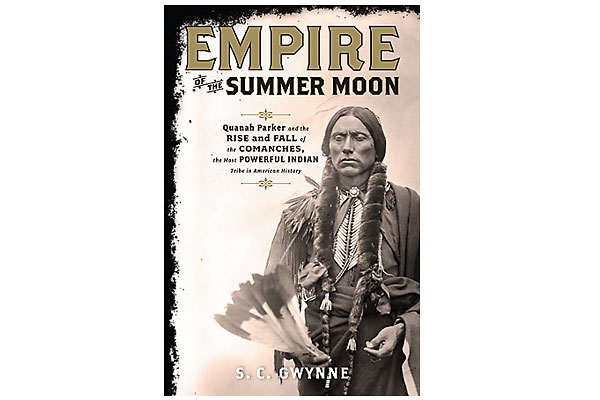

Quanah Parker, war chief of the last band of free-roaming Quahadi Comanches, faced the biggest battle of his life. But on this spring day in 1875 the fight would not be with the hated, blue-coated horse soldiers—it was with himself.

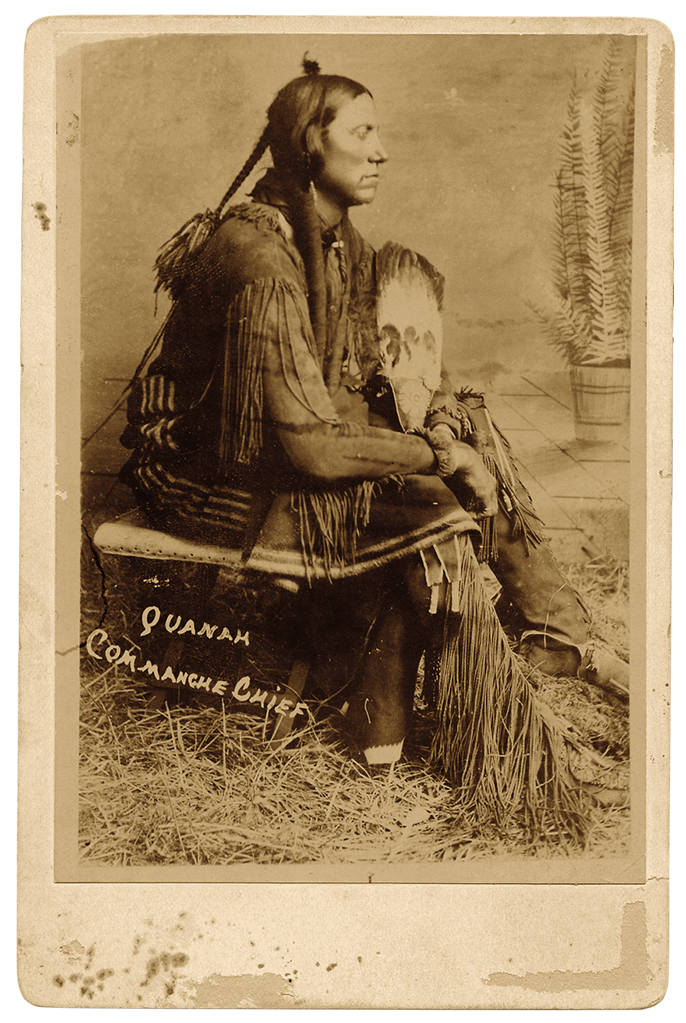

The son of Chief Peta Nocona and Cynthia Ann Parker, a white captive who adapted to Comanche ways only to be “rescued” by Texas Rangers in 1860 and forcibly returned to her birth family, Quanah had risen from young warrior to savvy war chief. He had been fighting for years to retain his people’s way of life on the huge expanse known as the Llano Estacado or Staked Plains.

Only a year before, in the heart of Comancheria, commercial buffalo hunters had established a trading post called Adobe Walls in present-day Hutchinson County, Texas. Their primary food source rapidly being decimated by the hide hunters, hundreds of Comanches and Kiowas led by Quanah attacked the enclave in June 1874. The hunters—seasoned marksmen—held off the Indians even though the defenders stood badly outnumbered.

The Adobe Walls attack triggered the Red River War, the U.S. Army’s 1874-75 campaign to force Quanah and his people to the Comanche-Kiowa reservation at Fort Sill in western Oklahoma. In a score of engagements or skirmishes, Quanah and his warriors fought hard, using well-honed guerrilla tactics to stave off a 3,000-man military force bent on their subjugation. But the Comanches, once considered all but invincible, were not going to prevail.

In early May 1875, with three Indian guides to help him find Quanah, Fort Sill post surgeon and interpreter Dr. Jacob J. Sturm was sent to deliver an ultimatum from Col. Ranald S. Mackenzie: Surrender or face annihilation. With roughly 100 warriors, Quanah was prepared to fight to the death. But he had the well-being of all his people to consider.

Was it time to take the white man’s road? The matter heavy on his mind and heart, Quanah rode alone from his band’s hidden camp in what is now Borden County, Texas, to Mushaway Peak, a landmark rising nearly 400 feet above the surrounding plains. With a buffalo robe draped over his head, the chief stood on the high ground pondering a decision that would have momentous consequences either way. As he took in the rugged landscape, he noticed a wolf in the distance. The animal raised its head and howled, then loped away to the northeast, in the direction of Fort Sill and the reservation. Then Quanah saw an eagle circling overhead. With a flap of its wide wings, the raptor banked toward the northeast as well.

Clearly, the chief concluded, the Great Spirit was telling him the day had come to quit fighting and lead his people to a new life of assimilation. In early June, the Quahadi left Texas to settle on the reservation. The unfettered freedom they’d enjoyed for generations had come to an end.

The Quanah Parker Trail

One hundred thirty-nine years later, a group of Borden County residents, historians, tourism officials, volunteers and Comanche tribal members stood in view of the peak in Gail, Texas, as workers embedded a 22-foot, 700-pound steel arrow in wet concrete. The arrow—one of 88 similar metal sculptures across the 52-county Texas Plains region marking sites related to the war chief and his people—sticks from the ground adjacent to the Borden County Museum, at U.S. 180 at Farm to Market Road 669.

The unique outdoor sculptures serve as waypoints along the Quanah Parker Trail, an expansive scattering of sites tied by history or legend to the clash of cultures that took place in the 1860s and 1870s on the Texas Plains. But unlike most trails, the QPT as it’s called, has no designated starting or ending place. Rather, as South Plains writer-historian-newspaper editor Dr. Barbara Brannon puts it, it is a “conceptual trail.”

Something else makes the QPT different: Don’t expect to find a brochure or web page with detailed directions to each arrow location. That said, most of the arrows are in plain sight (in parks, courthouse squares and outside museums), but some protrude from private property. As the QPT website QuanahParkerTrail.com puts it: “The Quanah Parker Trail wouldn’t be much of an adventure if you could find everything with just a mouse click or screen tap. So, take the challenge.”

In Comanche cosmology, the Great Spirit gathered swirls of dust from the four cardinal directions to create the Nermernuh, as they called themselves. Formed from the earth, the Comanche people had “the strength of the strongest storm.” One aspect of the QPT’s creation story connects in a quirky but fitting way with one of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s classic poems, “The Arrow and the Song” and its oft-quoted first verse: “I shot an arrow into the air, It fell to earth, I knew not where…”

Gid Moore, a Lynn County farmer and insurance agent, envisioned for his small town of New Home, Texas, a children’s park devoted to the great poets. With the famous line from Longfellow in mind, Moore commissioned New Home cotton farmer and longtime metal worker Charles A. Smith to build a large metal arrow that, when put in place, would look as if it, too, had been shot into the air and fallen to earth. When Smith completed the sculpture, Moore placed it on a piece of property he owned in town. The park Moore envisioned did not materialize, but in 2010 another, more ambitious public-oriented project was beginning to take shape on the northwest Texas plains.

The impetus for the QPT developed along an axis extending as straight as a Comanche war lance from Quanah, Texas (named in honor of the chief), through the Crosby County community of Ralls to Lubbock. In 2004, then Ralls City Manager J. Rhett Parker, a distant Parker relative who grew up hearing stories about the famous chief, suggested to Quanah’s mayor that developing a trail devoted to Quanah Parker-related sites would be a worthy heritage tourism project.

The idea lay dormant until 2009, when Quanah’s Main Street Program Director Hanaba Munn Welch drew inspiration from a traveling exhibit on Quanah’s life she saw in Arlington. She arranged for the exhibit to go on display at the Hardeman County Historical Museum in Quanah and went to work on the trail project. With input from then-Texas Plains Trail Coordinator Deborah Sue McDonald, Welch designed a Quanah Parker Trail website in 2010. Later that year the trail concept developed further at a meeting involving Welch, McDonald, Three Rivers Foundation Arts Director Carolyn Wilson and other Quanah civic leaders and Parker family representatives.

On the Lubbock end of the imaginary feather-draped spear, educator and artist Dr. Holle Humphries and Dr. Tai Kreidler, executive director of the West Texas Historical Association, got involved in the effort early on. Humphries is now the QPT facilitator and also serves on the nonprofit Quanah Parker Trail steering committee.

The Arrow Trail

As the QPT began to take shape, the grassroots coalition realized they needed a fitting symbol to distinguish the proposed trail from other heritage tourism initiatives. Suggestions ranged from a Comanche shield to an eagle feather, but none seemed quite right. And then one day in January 2010, with McDonald behind the wheel and Dr. Humphries riding shotgun, as they drove through New Home on their way to Lubbock, Humphries saw a giant arrow sticking in the ground in the middle of a vacant field. She asked McDonald to turn around, and they went back for a closer look. As they approached the striking sculpture, the wind blowing through the long arrow’s steel-rod flanges made a gentle musical sound.

No signage explained the purpose of the art piece or who owned it. Struck by the attention-getting arrow, Humphries called the nearby high school hoping to learn who had put it up. The first person she talked with said the arrow was the creation of Charles Smith and gave Humphries his phone number. When Humphries talked to Smith, he readily agreed to make more of his singing arrows at no cost, as long as Parker’s descendants and the Comanche Nation were on board with the program—which they were. All Smith wanted was a receipt from each entity accepting one of his arrows, a document he used for income tax deduction purposes.

The first arrow, with bands of red, blue and yellow—the Comanche Nation colors—ringing the shaft just below the flange, was installed at Matador in October 2011 next to the old Motely County jail. A marker placed near the arrow points out that one of the Quahadi’s favorite campsites had been near here. With the arrows carried in a special trailer also designed by Smith, the placing of additional arrows continued apace across the 50,000-square mile region. Descendants of the Parker clan and other Native Americans often took part in dedication ceremonies, offering music and cedar-smoke blessings, and educating history buffs and school children alike. The result is one of the nation’s largest unique works of public art.

Visiting all 88 arrow locations, which range across an area stretching 306 miles from Stratford on the north to Big Spring on the south, would take a while. But the modern-day Western history aficionado can get a good feel for the story this massive project tells by visiting a few key points. To do that, think like the nomadic Comanche people. Archaeologists say that Comanches and other Plains tribes seldom camped anywhere for more than three days. Otherwise, the hundreds of horses they owned would eat all the grass. The People, as they called themselves, moved from campsite to campsite based on the availability of water, grass, firewood and the buffalo they needed to survive.

Depending on which direction you’re coming from, the two best modern-day “campsites” are Amarillo, which sits astride Interstate 40 (the old Route 66) in the upper part of the region, and Lubbock, 120 miles south of Amarillo via Interstate 27.

Long before Amarillo began as a rail stop in the late 1880s, the Tascosa Trail cut across the Panhandle through future Potter County. On the far northwestern edge of the city, one of the more visually striking of the QPT arrows rises in a place that remains much as it did in Quanah’s time, Wild Cat Bluff Nature Center, 2301 North Soncy Road. The arrow is seated dramatically in a stacked stone base. Nearby is a granite marker that reads: “Indians hunting bison for centuries established Tascosa Trail nearby, used by traders and buffalo hunters.”

Made of gray granite, and set nearly flush to the ground, the QPT markers are provided at cost by a monument company in Clarendon, Texas. The concise three-lines-only text for each marker—a history haiku of sorts—is checked for accuracy and cultural sensitivity by the QPT steering committee and other partners, from county officials to historians to the Parker family and the Comanche Nation. Those involved with the QPT effort are quick to point out that they are not attempting to rewrite history, only to offer a balanced perspective on one of the American West’s more compelling stories.

Back to planning your QPT exploration: After checking out the Kwahadi American Indian Museum at 9151 I-40 East in Amarillo, travel 21 miles south of Amarillo on I-27 to Canyon, home to the Panhandle Plains Historical Museum. The museum—Texas’s oldest devoted solely to history—has exhibits on the Comanche people. Among the artifacts on display are a headdress, lance and Winchester rifle that belonged to Quanah.

Fourteen miles east of Canyon via State Highway 217 is the sprawling Palo Duro Canyon, the nation’s second-largest canyon. Much of the canyon, which is roughly 120 miles long and averages 6 miles wide, is part of Palo Duro Canyon State Park. The park has a visitor center interpreting the natural and cultural history of the canyon along with campgrounds, rental cabins and miles of hiking trails. It was here in the fall of 1874 that Mackenzie and his troopers charged a Quahadi camp on the canyon floor and captured hundreds of the Comanches’ horses.

From Canyon, head back to Amarillo and rest up around your figurative campfire for a side trip to the site of the 1874 Adobe Walls fight, the confrontation that led to the Red River War, the 1874-1875 military campaign that resulted in the final subjugation of the Comanche people. In Borger, the nearest town of any size, check out the Hutchinson County Historical Museum, which has exhibits devoted to Adobe Walls. The arrow sculpture stands adjacent to the museum.

Amarillo to Lubbock

Leaving Amarillo for a new base camp in Lubbock, you’ll pass through Tulia in Swisher County. An arrow near Tule Canyon marks the place where soldiers slaughtered hundreds of captured Comanche horses. The arrow stands just across from a gray granite marker put up during the Texas centennial celebration in 1936. Near the arrow is a new marker noting: “Quanah Parker never forgot that near this site Sept. 29, 1874 the U.S. Army shot 1,048 Indian horses.”

After checking out the Quanah-related exhibit at the Swisher County Archive and Museum, take State Highway 86 east to Quitaque and the 15,300-acre Caprock Canyons State Park. An arrow and marker are near the park, which is home to the state bison herd.

In Lubbock there’s an arrow on the grounds of the FiberMax Center of Discovery (1121 Canyon Drive) commemorating a battle the Comanches had with buffalo hunters in nearby Yellow House Canyon, a once perennial Comanche camping place. The Museum of Texas Tech University (3301 4th St.) has permanent and rotating exhibits. And while the nationally recognized American Windmill Museum and Ranching Heritage Center are a must-sees, they deal with the post-Comanche period of Texas Plains history.

Just south of Lubbock is the original arrow, which now has a granite QPT marker explaining Charles Smith’s critical role in the trail project. Before he died in 2018, Smith was adopted into the Quanah Parker family and given a Comanche name, Paaka-Hani-Eta. It means “arrow maker.”

Lubbock to Quanah

From Lubbock, it’s 157 miles along U.S. 62 to Quanah. In addition to the exhibits on the chief in the Hardeman County Historical Museum, there’s more on him at the nearby Quanah, Acme and Pacific Depot Museum. A granite monument to the chief stands on the courthouse square. Fourteen miles southeast of Quanah is the ghost town of Medicine Mound, named for two rounded hills that are still considered sacred Comanche places. The Downtown Medicine Mound Museum tells the story.

A different approach for your arrow hunt is to follow the Texas Plains Trail, one of ten regional trails developed by state tourism officials in the 1960s. This blue-and-white sign-marked trail connects 21 communities with notable attractions and heritage sites in the Panhandle and South Plains. A map of the loop trail, which moving clockwise from Amarillo includes Canyon, Claude, Silverton, Turkey, Matador, Crosbyton, Post, Tahoka, Slaton, Lubbock, Levelland, Morton, Muleshoe, Hereford, Vega, Boy’s Ranch (the site of the old town of Tascosa), Dumas, Fritch, Borger, Panhandle and then back to Amarillo. All of these communities have QPT arrows or are not far from one.

How far you choose to range along the QPT can be measured in miles, but there is a more appropriate metric. As the trail website puts it: “More meaningful than the miles Quanah traveled is the distance he covered between disparate cultures and the transition he made between different ages in the history of the American West. For better or worse, Quanah led his people into the 20th century.”

Wide Spot in the Road: Texas

Mobeetie, Texas

The only fort the Army garrisoned on the Texas high plains was Fort Elliott, established in 1875. The presence of the fort in the northeastern corner of the Panhandle fostered the growth of a collection of saloons, brothels and more conventional businesses that became the town of Mobeetie. Nothing remains of the old fort, abandoned in 1890, but a state historical marker stands on the site. At Mobeetie, first known as Sweetwater, see the Old Mobeetie Jail Museum at 300 Olaughlin Street. Housed in the restored 1896-vintage old Wheeler County hoosegow, the museum has displays on the Red River War, Fort Elliott and Mobeetie’s wild and woolly days. Bat Masterson, who went on to greater fame, shot and killed a soldier here in 1876 while he was making a living as a buffalo hunter. The original Fort Elliott flagpole now stands outside the museum, and nearby is one of Charles Smith’s giant arrows. WheelerTexas.org

Good Eats & Sleeps:

Eats: Tyler’s Barbeque, Amarillo; The Plaza, Borger; Feldman’s Wrong Way Diner, Canyon; Cast Iron Grill, Lubbock; Medicine Mound Depot Restaurant, Medicine Mound

Sleeps: Barfield Hotel, Amarillo; Hudspeth House Bed & Breakfast, Canyon; Cotton Court Hotel, Lubbock

Longtime Texas writer Mike Cox, an elected member of the Texas Institute of Letters, has written more than 35 nonfiction books. He was born in Amarillo in the heart of Quanah Parker’s former homeland.