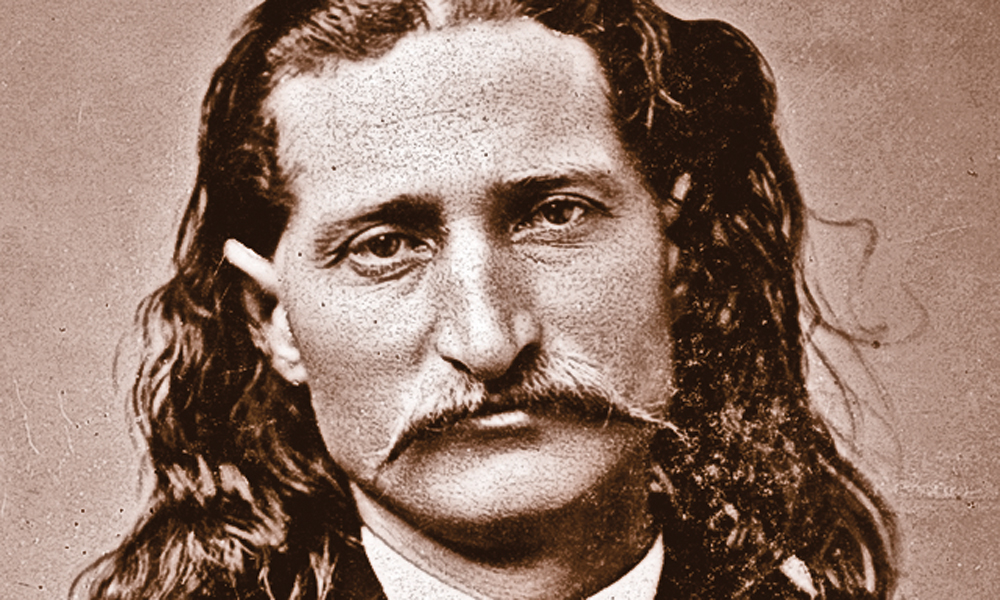

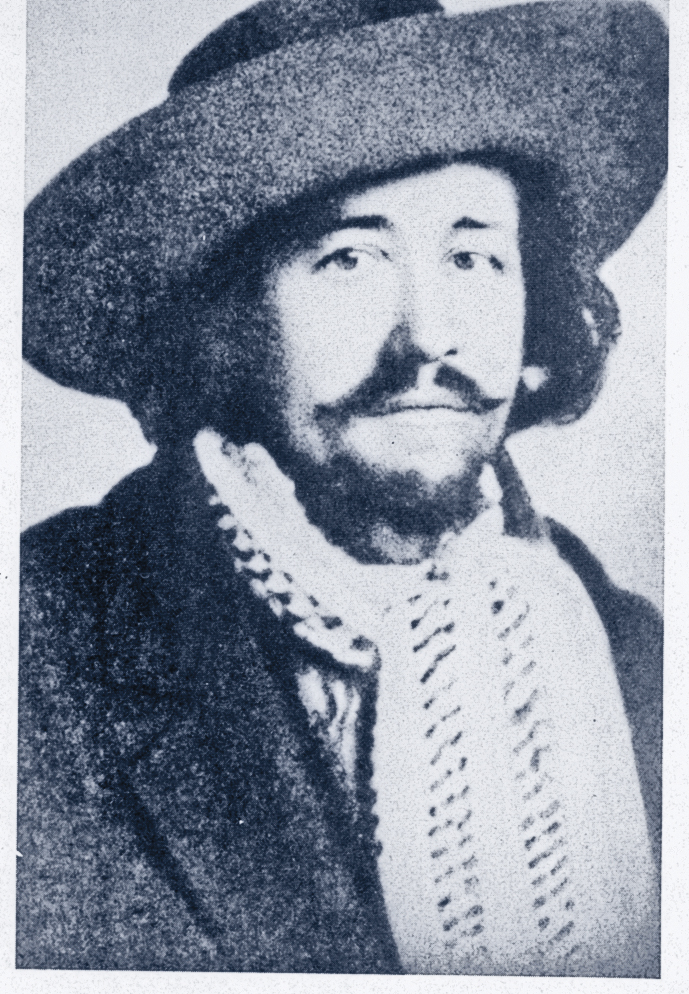

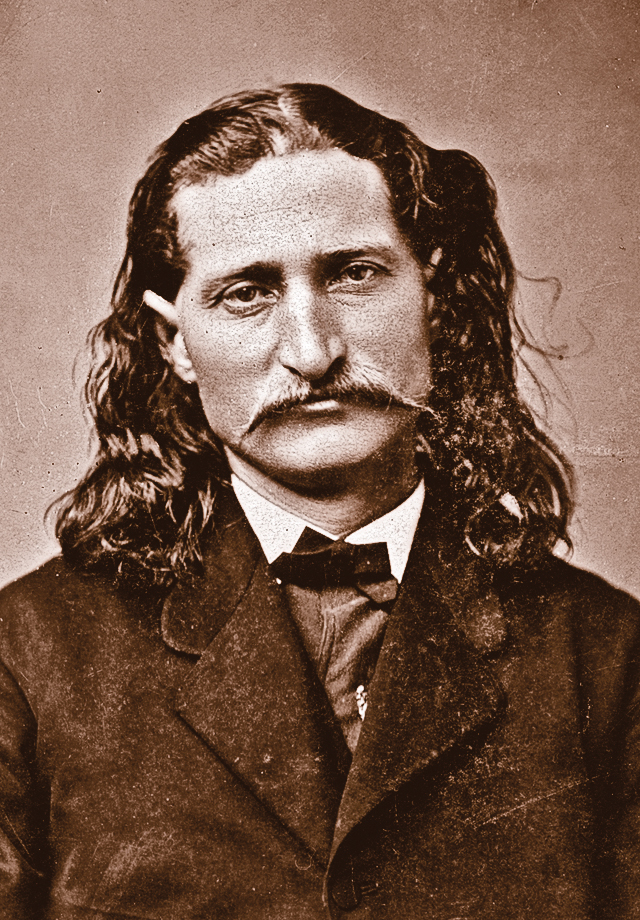

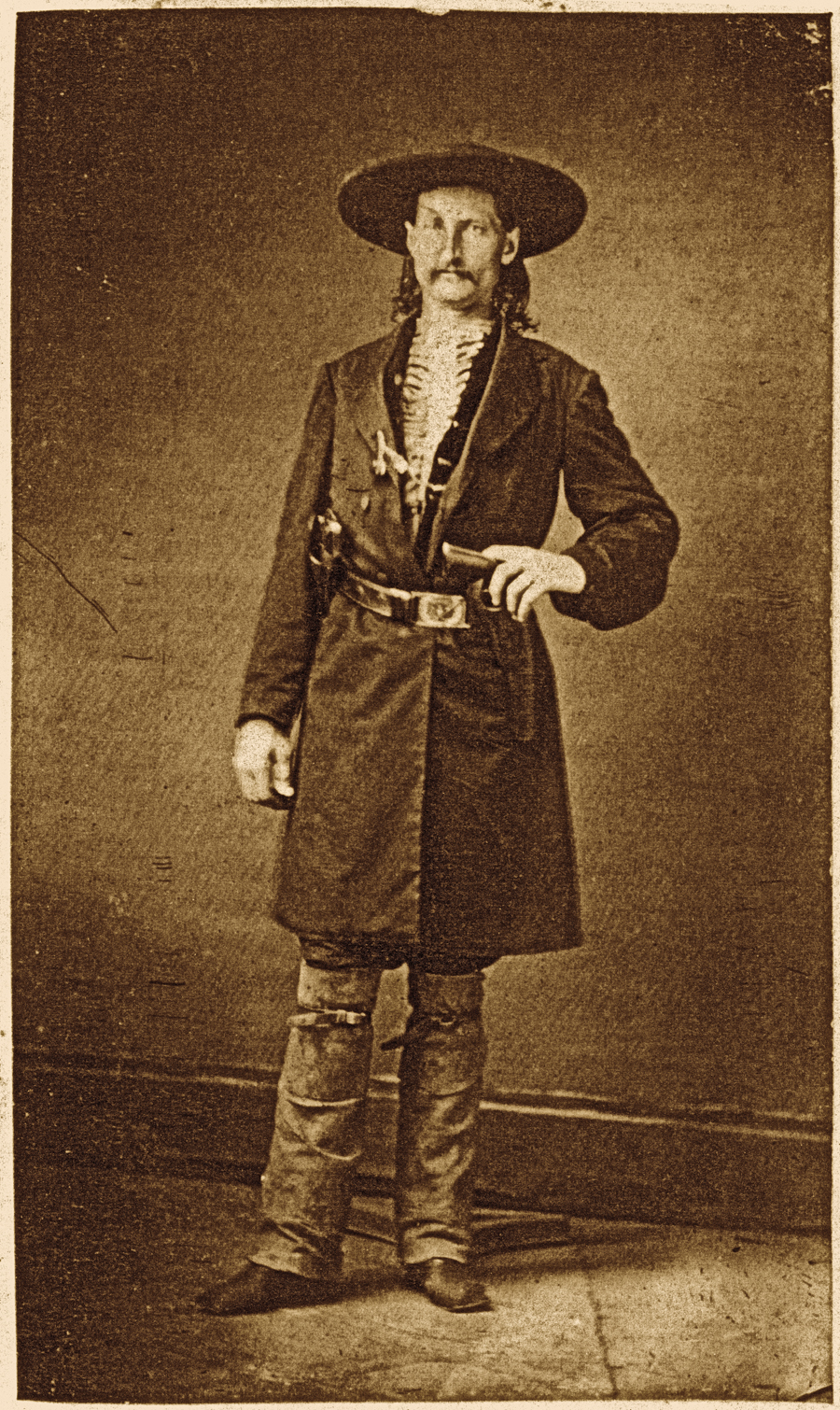

James Butler Hickok, born on a farm in northern Illinois in 1837, leaves home at age 18, gravitating to Kansas Territory, with his brother Lorenzo, in 1856. James works at various frontier jobs, including teamster and stage driver. Within the next 20 years, he will become known as the “greatest of all Western scouts.” Or, so claims legendary U.S. military leader George Custer.

In his day, James is described as a farmer, a vigilante, a teamster, a spy, a lawman, a gambler, a gunfighter and a bad actor. One account describes James as “…a drunken, swaggering fellow, who delighted when ‘on a spree’ to frighten nervous men and timid women.”

James’s greatest strength—his speed and accuracy with pistols—will turn out to be his greatest weakness. His life as the Prince of the Pistoleers is about to begin, and that’s where we will start.

July 12, 1861 – James Butler Hickok vs David McCanles

David McCanles, his son, William, and two employees ride up to Rock Creek Station in Nebraska Territory. Leaving his hired hands at the barn, David and son go to the main house and tell the occupants to clear out.

Horace Wellman, the Pony Express station keeper, refuses, saying David has no such authority (see “The Deadly Deal,” p. 20). An argument ensues, and a frightened Horace retreats into the house while Jane, Horace’s common-law wife, stands outside the doorway and berates David for an earlier incident, during which he had thrashed her father over an alleged theft.

James Butler Hickok, an assistant station tender not yet known as Wild Bill, appears in the doorway. David advises him to keep away.

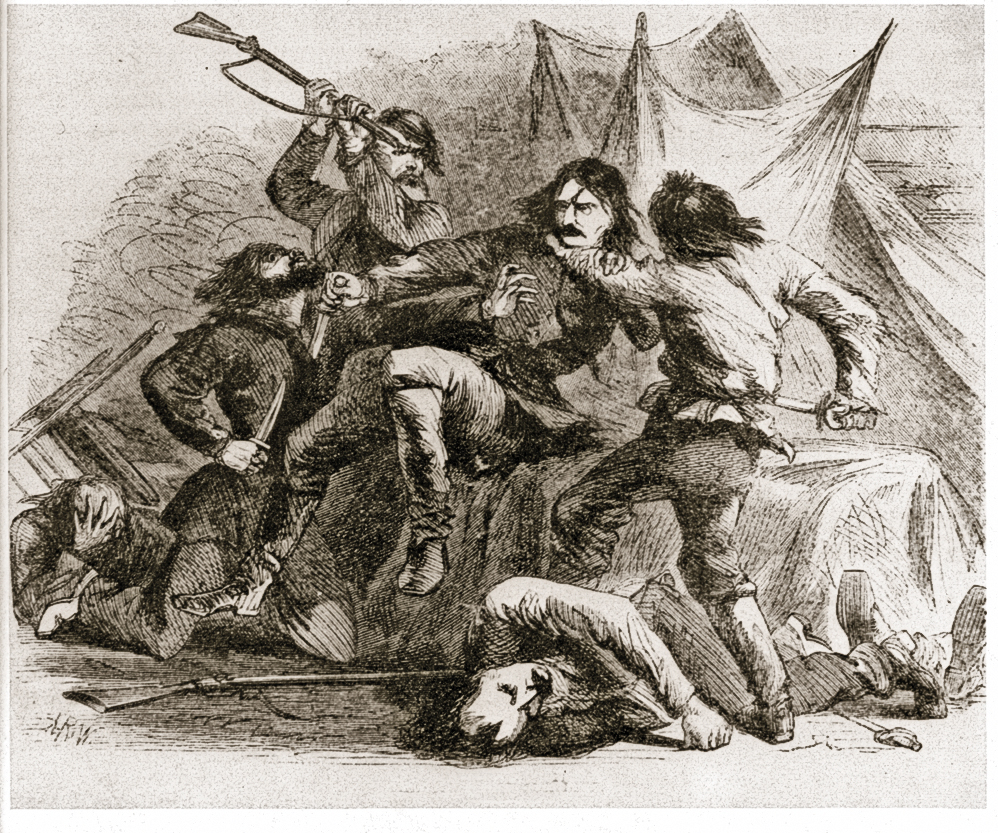

A known bully, David is usually armed with a pistol and shotgun, but historians do not know if he carried those weapons that day. He makes a fatal mistake when he asks Hickok for a drink of water. Moments after he steps inside the house to get it, Hickok allegedly fires a shot that kills David.

James Woods and James Gordon, David’s employees, rush up from the barn and are shot, though not fatally. Jane supposedly smashes Woods’s skull with a hoe, perhaps aided by her still-frightened husband.

Gordon escapes into the brush, but his bloodhound follows him, and his pursuers follow his blood and the dog. He is killed by a shotgun blast, supposedly by James W. “Doc” Brink, a Pony Express rider.

David’s son, William, runs to his father’s side, but Jane drives him away. The boy safely escapes into the brush.

Three days later, lawmen arrest James, Horace and Brink, charging them with murder. They are released when the judge rules the trio was defending company property.

Rock Creek Station

A regular camping spot on the Oregon Trail, Rock Creek is first known as Weyth Creek. The Pony Express station can be seen in the circa 1861 photo below. Rock Creek “cut and intersticed with deep, irregular gorges and canyons, through which flow crystal streams, fed by the springs that issue from the walls of rock under the hills. Giant oaks, elms and cottonwoods studded the banks of these streams, and the little flats in the bends of its winding course, rank in growth of primitive grasses, with the hillsides surrounding clothed with the shorter grasses suitable for pasturage,” wrote Charles Dawson, in 1912.

The Deadly Deal

Fleeing North Carolina in 1859 with his mistress, Sarah Shull (shown with her below), and misappropriated county funds, ex-Sheriff David McCanles settled in Rock Creek, Nebraska Territory. He bought a small overland station and corral, and improved them. He later built a ranch close by and sent for his family. His wife and kids showed up to find Shull (described as a domestic in census returns), which made Mrs. McCanles furious. But she put up with the presence of the mistress—barely.

In April 1860, Russell, Majors & Waddell organized the Pony Express and rented Rock Creek as a relay station. The company negotiated to pay David one-third down, with the remainder to be paid in three monthly installments.

By June, David was concerned about delinquent payments, and he persuaded the station keeper, Horace Wellman, to travel to company headquarters and investigate. David’s 12-year-old son, William, accompanied Wellman. When they returned on July 11, Wellman reported the Pony Express company was bankrupt.

The next day, an upset David rides over to Rock Creek to evict the tenants. He is unsuccessful.

Wild Bill and the Ladies

More than a few ladies are enchanted by James Butler Hickok. “He was really a very modest man and very free from swagger and bravado,” Libby Custer, wife of George, notes.

When Louisa Cody, wife of showman Buffalo Bill, met Hickok at a dance in 1870, she described him as a “mild-appearing, somewhat sadfaced man” who “bent low in a courtly bow.” And then they danced—more than once.

In 1871, Hickok meets his future wife, Agnes Lake Thatcher, the widow of a circus owner. After several years of correspondence, the lovebirds marry on March 5, 1876, in Cheyenne, Wyoming Territory.

July 21, 1865 – “Wild Bill” Hickok vs Dave Tutt

Dave Tutt walks onto the town square in Springfield, Missouri, at 6 p.m. on a Friday. He is about to face off with a known adversary, James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok.

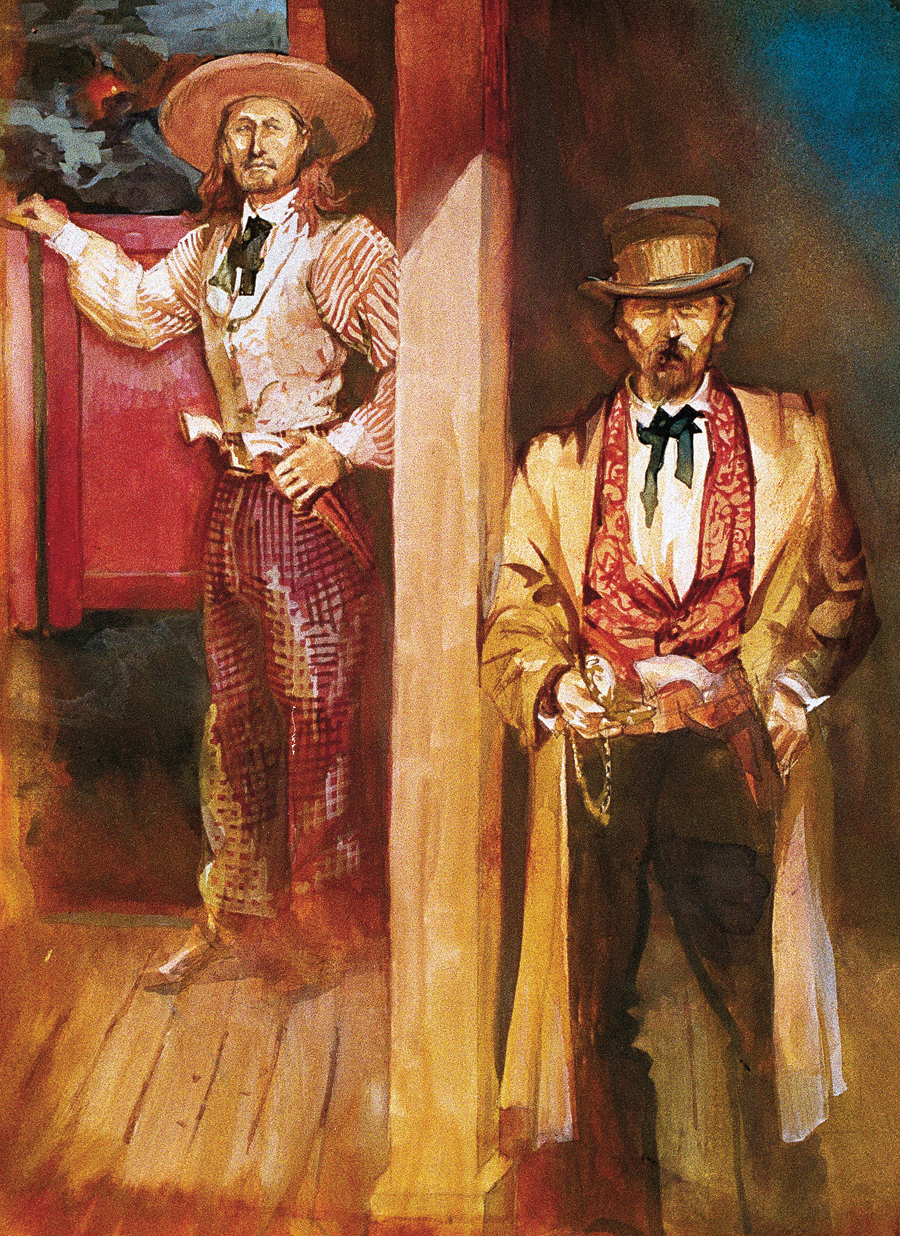

Wild Bill and Tutt step onto the street, dressed to the nines, each with “two revolvers strapped to their belts.” Both are “noted scouts, desperadoes and gamblers.” Although they were once friends, they got crossways with each other. Rumors have been circling that their tiff is over a woman.

This feud begins over gambling.

The former friends were playing cards when Wild Bill refused to play with Tutt again because he kept picking fights. To keep in the game by proxy, Tutt gave money to every man who played cards with Wild Bill. Unfortunately for Tutt, Wild Bill was winning all the hands.

Another night, at the Lyon House, Tutt accused Wild Bill of owing $40 for a horse trade. After Wild Bill reportedly paid him, Tutt asked for another $35, claiming it was an outstanding debt from a previous game. Wild Bill replied that the debt was only $25, but Tutt took Wild Bill’s prized Waltham repeater watch, from the table, as collateral.

Not amused, Wild Bill announced that Tutt should not show off this prized possession. Wild Bill’s threat spurred on Tutt, who vowed to “pack that watch across the square next day at noon.” Wild Bill replied to Tutt’s boast: “Tutt shouldn’t pack that watch across the square unless dead men can walk.”

Now Tutt is on the square, and he is strutting.

From across the square, Wild Bill yells at Tutt, advising him not to carry the watch. Tutt puts his hand behind him, but instead of reaching for the watch, he pulls out his pistol.

Both men fire “simultaneously…at the distance of about 100 paces,” says Col. Albert Barnitz, the military commander of the Springfield post who witnesses the duel.

When Wild Bill’s shot hits Tutt in the heart, the gambler stumbles backwards and falls near the steps of the courthouse. Tutt is dead.

Barnitz arrests Wild Bill, who ends up charged with murder.

July 17, 1870 – “Wild Bill” Hickok vs The 7th Cavalry

Deputy U.S. Marshal James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok converses with the bartender in Paddy Welch’s Place in Hays City, Kansas. Without warning, two 7th Cavalry troopers attack Wild Bill from the rear, pinning his arms and wrestling him to the floor. A newspaper later reports that “five soldiers attacked Bill.”

One trooper, powerful pugilist Jeremiah Lonergan, pins down Wild Bill and does everything in his power to keep the deputy marshal’s arms away from his body…and his pistols.

An eyewitness claims that a second soldier, John Kile, whips out a Remington pistol from underneath his blouse, “puts the muzzle into Wild Bill’s ear, and snaps it.” The pistol misfires.

Amid the yelling and ensuing commotion, Wild Bill and the two soldiers grapple on the floor, each trying to get an advantage. At some point, Wild Bill receives a leg wound, either from a gunshot or the scuffling.

Despite Lonergan’s best efforts, Wild Bill removes one pistol from his holster and fires a round, hitting Kile in the wrist. A second round hits Kile in the side, and he rolls away in agony.

Lonergan desperately fights for his life as he tries to keep Wild Bill’s pistol barrel pointed away from him. Pushing against the much larger man, Wild Bill fights with all his might, finally turning his pistol far enough to fire. The resulting shot hits Lonergan in the kneecap.

Stunned, Lonergan gives up his grip and joins Kile on the disabled list. Wild Bill wastes no time. He scrambles to his feet, “makes tracks for the back of the saloon,” jumps “through a window, taking the glass and sash with him,” and makes good his escape.

When news of the gunfight reaches Fort Hays, a number of troopers seize their guns, head for Hays City and search all the “saloons and dives,” but they cannot find Wild Bill.

Deadly Sheriff

In August 1869, in his first month as sheriff of Ellis County, Kansas, “Wild Bill” Hickok kills a drunken man in Hays City, Bill Mulvey (or Melvin), “through the neck and lungs,” to stop him from rampaging through town, shooting out saloon mirrors and whiskey bottles. The next month, he aims his deadly pistol at Samuel O. Strawhun, for causing a ruckus in John Bitter’s Beer Saloon. The people must have felt they got a different kind of “law” than they wanted; on November 2, Hickok is defeated in the sheriff election by his deputy, Peter Lanahan.

Wild Bill’s Luck Runs Out

Most people think Hollywood created the “fast draw,” but here is a contemporaneous comment on “Wild Bill” Hickok’s speed, published by the Chicago Tribune, on August 25, 1876:

“The secret of Bill’s success was his ability to draw and discharge his pistols, with a rapidity that was truly wonderful and a peculiarity of his was that the two were presented and discharged simultaneously, being ‘out and off’ before the average man had to think about it. He never seemed to take any aim, yet he never missed.”

Wild Bill’s fast draw is his greatest strength, but it soon proves to be a weakness.

The First Queen of the Cowtowns

Named after the Biblical city of the plains, Abilene is the first Kansas cowtown. First a stagecoach stop and then a stop on the tracks of the Union Pacific Railway (Eastern Division), Abilene becomes a cattle shipping point when Joseph McCoy sets up operations there. A cattle buyer from Illinois, McCoy wanted to find a shipping point clear of the restrictions against Texas Longhorn cattle. The Lone Star bovines carried a tick that transferred splenic fever, known as Texas fever. Abilene is far enough west that the incoming herds will not contaminate domestic stock. The first cattle season, which traditionally runs from May to October, begins on September 5, 1867, when the first train loaded with Texas cattle heads east.

Abilene does not have a local lawman until the appointment of Tom Smith in 1870. But he is murdered that November. After a few stopgap lawmen come and go, the town appoints “Wild Bill” Hickok on April 15, 1871. He serves eight months until the town relieves him of his duties.

October 5, 1871 – “Wild Bill” Hickok vs Phil Coe

The summer cattle season is all but over, and Marshal James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok has kept the peace in Abilene, Kansas—not an easy job. The last marshal, legendary Thomas J. Smith, was killed in the line of duty. Plus, Wild Bill is not popular with the Texans in the town, having cleaned out the brothels the month before, on the order of the city council.

When heavy rain sullies the town’s Dickinson County Fair, about 50 cowboys wander from saloon to saloon on the main drag, bullying and intimidating patrons into buying them drinks. Some accounts suggest the cowboys pull this trick on Wild Bill, sweeping him off his feet and carrying him into a saloon. Wild Bill humors the boys and buys them a round.

Rumors swirl that Texas gambler Phil Coe has sworn to get Wild Bill “before the frost.” Many citizens make themselves scarce as the evening wears on, fearful that things may get out of hand.

At about 9 p.m., Wild Bill hears a shot fired outside the Alamo Saloon. He earlier warned the cowboys against carrying firearms, so he confronts the group standing in front of the Alamo and encounters Phil Coe, with a pistol in his hand.

Coe claims he fired at a stray dog, but as he says this, he pulls another pistol and fires twice; one ball goes through Wild Bill’s coat, while the other thuds into the ground between his legs.

Wild Bill reacts in a flash and, “as quick as thought,” according to the Chronicle, pulls his two Colt Navy revolvers and fires, shooting Coe twice in the stomach.

Others in the crowd are hurt. When another man brandishing a pistol emerges from the shadows, Wild Bill, not recognizing him in the glare of the kerosene lamps and his nerves on high alert, instinctively fires. When he sees the man, he realizes he has killed Michael Williams, a personal friend of his and a one-time city jailer.

Wild Bill carries Williams into the Alamo and lays him down on a billiard table, then turns and disarms everyone he can find. The marshal warns them all to clear out of town. Within an hour, the place is deserted.

Devastated, Wild Bill’s days as a mankiller are over.

A Man Out of His Element

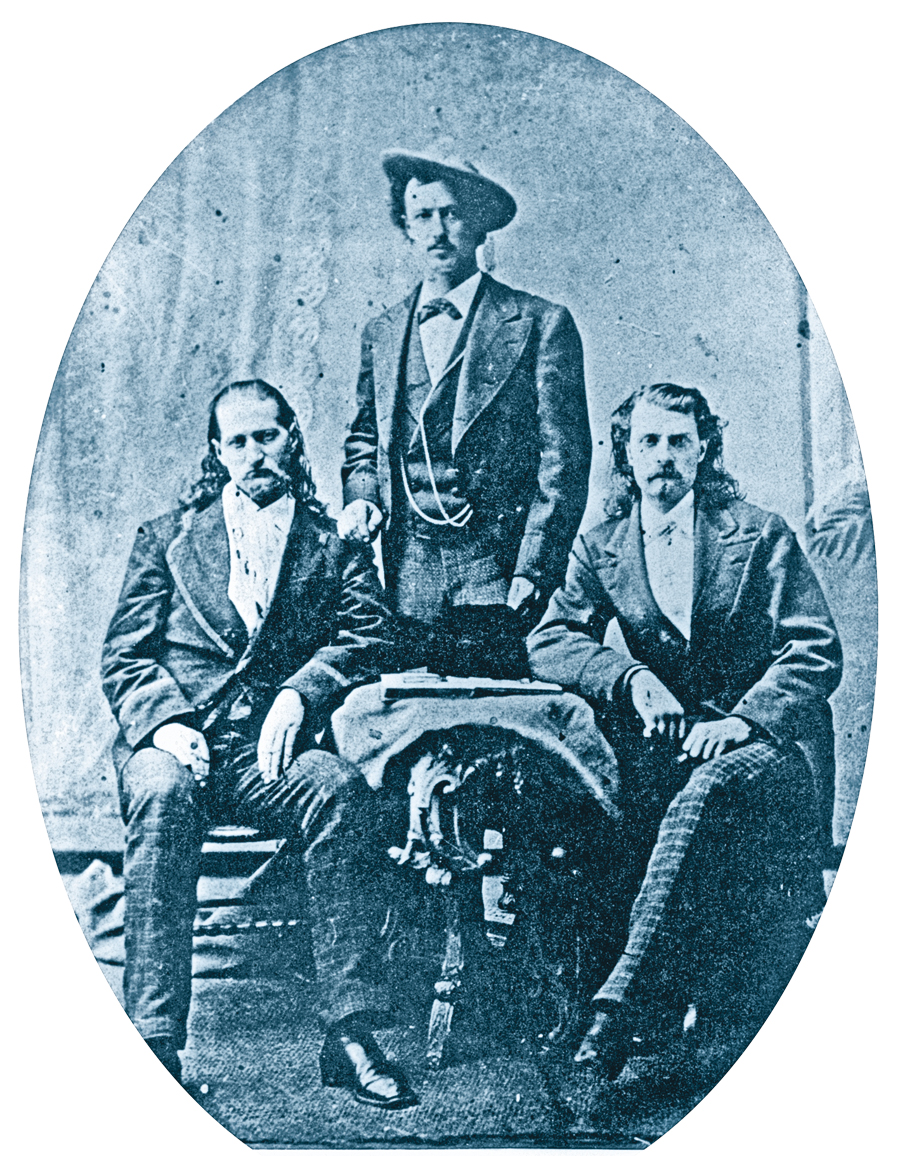

Wild Bill returns to the West in 1874, bouncing around quite a bit. On July 18, he rides a train through North Topeka, Kansas, on his way to meet “Buffalo Bill” Cody and “Texas Jack” Omohundro in Cheyenne, Wyoming Territory. Later that day, in Kansas City, Missouri, 12 English lords hire Wild Bill as a scout for their hunts. Between trips to St. Louis and Kansas City, he makes Cheyenne, Wyoming Territory, his base for the next two years.

In 1875, Wild Bill goes missing, despite a couple glimpses of him in the press. On June 17, he is arrested in Cheyenne and charged with vagrancy. Some surmise that he has hit rock bottom.

A New Start

A turning point for Wild Bill is his marriage to Agnes Lake Thatcher, on March 5, 1876. After a short honeymoon at her home in Cincinnati, Ohio, Wild Bill returns to Cheyenne, Wyoming Territory, to organize an expedition to the Black Hills.

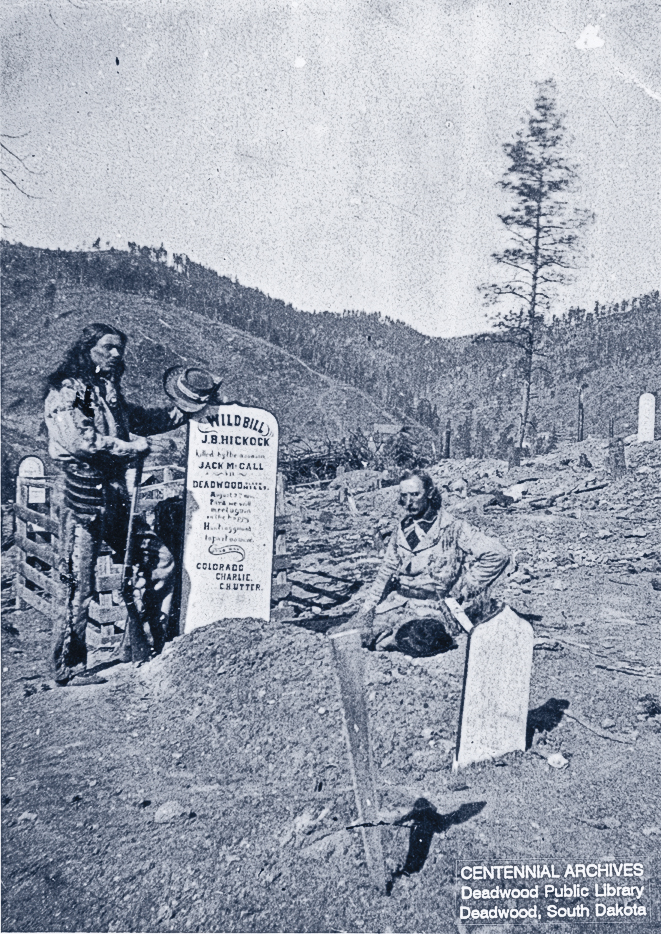

Leaving for Deadwood, Dakota Territory, on or about June 27, Wild Bill’s party grows during the journey. By the time he reaches Deadwood, around July 12, the group includes several prostitutes, among them Calamity Jane.

Wild Bill spends less than a month in Deadwood; it is his last stop.

August 2, 1876 – “Wild Bill” Hickok vs Jack McCall

ild Bill Hickok walks from his camp on the edge of Deadwood, Dakota Territory, to the Lewis, Nuttall and Mann’s No. 10 Saloon. Entering around noon, he encounters about a half-dozen men. Three men are playing draw poker. Wild Bill recognizes Missouri River steamboat captain William R. Massie and Charlie Henry Rich, a card dealer Wild Bill knows from his days in Cheyenne, Wyoming Territory. Wild Bill joins their game.

Wild Bill sits in the only available seat, near the rear entrance of the saloon, facing the front door. He usually sits along the west wall, but Rich is occupying that seat. Wild Bill prefers that seat’s view of the entire room, including good views of the front and back doors, and asks Rich for his “regular” seat, but the gambler refuses to move.

Wild Bill, uncomfortable with the fact that his back is exposed to the open bar and rear door, once again asks Rich to trade places. This time, the other players chide Wild Bill, telling him he has nothing to worry about this early in the day. Wild Bill takes the empty seat.

The four men have been playing draw poker for almost three hours when Jack McCall (also known as Bill Sutherland) walks through the front door, heads over to the bar, pauses, then moves down the length of the bar, stopping momentarily at the scales sitting on the end of the bar.

Wild Bill throws down his hand in disgust and says, “The old duffer, he broke me on that hand.”

McCall steps forward, pulls a pistol from his clothing and points it at the back of Wild Bill’s head, pulling the trigger at the same instant.

The bullet exits out Wild Bill’s right cheek near the bottom of his nose. His head moves slightly forward, and he is still for a moment. Then he falls sideways off his stool onto the floor.

He dies instantly.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

The bullet that killed James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok passed through and hit William R. Massie in his left arm above the wrist. The riverboat pilot thought Wild Bill had become enraged over losing and shot him, but then Massie saw Jack McCall standing over the table with a gun, threatening all the players. Backing toward the rear door, McCall screamed at everyone, “Come on ye sons-a-bitches!” He cocked his pistol and fired, but the pistol failed to shoot. He cocked it again to fire at George Shingle, who had moved out from behind the bar to help Wild Bill, but the gun misfired again. McCall fled.

Captured and tried the next day in the new Deadwood Theatre, McCall testified Wild Bill had shot his brother in Kansas two years earlier and that the killing was an act of vengeance. The jury of miners found him not guilty. McCall left town and headed to Laramie City, Wyoming Territory, where he bragged about killing the great Wild Bill. Colonel George May obtained a federal arrest warrant and took McCall into custody on August 29, 1876.

Eventually tried in federal court, in December 1876, in Yankton, the Dakota Territorial capital, McCall admitted he had lied about Wild Bill killing his brother. The killer was found guilty and hanged on March 1, 1877. McCall was buried with the hangman’s noose still around his neck in an unmarked grave in the local Catholic cemetery.

Recommended: The West of Wild Bill Hickok and They Called Him Wild Bill by Joseph G. Rosa, published by University of Oklahoma Press