Remembering my great-grandfather’s role in the creation of a classic Western fiction and

film character.

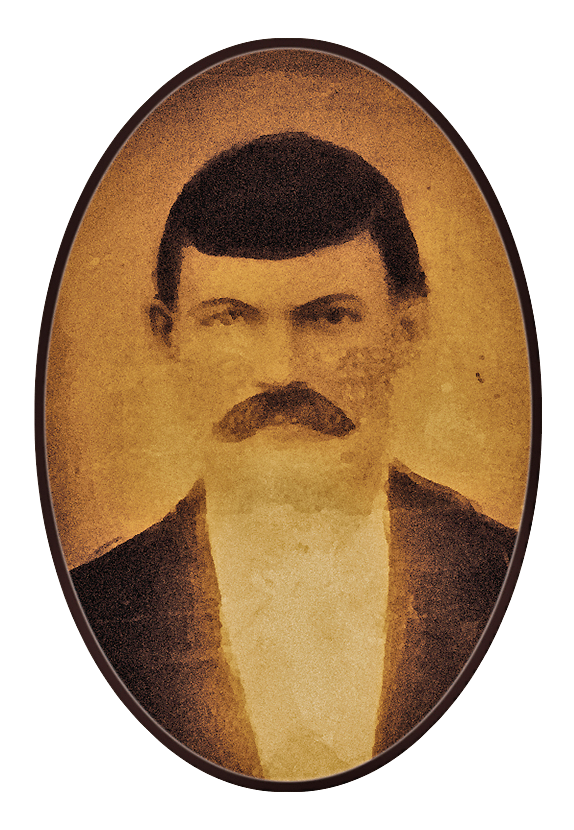

John Franklin Cogburn, nicknamed “Rooster” by his Uncle Page, was my great-grandfather.

While he never packed a badge, Franklin was quite familiar with the operations of the deputy U.S. marshals riding out from Fort Smith, Arkansas. On June 21, 1888, Franklin, with the aid of his cousin Fayette, attacked a posse of those stalwart lawmen during a raid on moonshiners near Black Springs. Deputy Marshal J.D. Trammel was killed in the gunfight that followed.

Six foot three, dark-eyed and a dead shot with a rifle, Franklin was as hard as the rocky mountain ground which reared him. The only authority the Cogburn clan recognized was God and a gun. Governments didn’t build your home, make your clothes, hunt your meat or defend your life. When it came to the Law, a man rolled his own from the makings of his individual ideas of right and wrong.

Franklin had lost his father from a disease incurred in a Confederate prison camp. As a teenager he fell under the influence of his Jayhawker uncle, Henry Page Cogburn, the man who ran Gen. Albert Pike out of Arkansas in an attempt to steal the gold the general was said to have embezzled from the Confederacy.

Bad blood already existed between the Cogburns and Deputy Trammel long before that fatal morning in 1888. Trammel had been working undercover to identify moonshiners and apparently used strongarm tactics on the Cogburn womenfolk while the men were away. On the day before the gunfight, Deputy Marshals Trammel and Reuben M. Fry, along with a 15-man posse, had arrested Joseph Peppers and Franklin’s brother Bill. Franklin led Fayette and three other hard-riding mountain boys to confront Trammel and two posse members. A shot from a Cogburn Winchester ended Trammel’s life.

Knowing the kind and numbers of men they were up against—nearly every man in the county was either a Cogburn, kin or friend—Deputy Fry went to Fort Smith for help. He left four deputies in Black Springs to guard Bill Cogburn, but they decided to flee on horseback to Hot Springs. The Cogburns pursued them, and the deputies just managed to get their prisoner on the train to Fort Smith.

A reward of $500 per man was posted in the newspapers for the capture of Franklin, Fayette and three others. Fearless of the courts and seeing a way to get the reward, Franklin had his father-in-law, Joseph Spurling, turn him over to a grand jury set to indict Trammel’s murderers.

The court was scared into inaction when a large number of the Cogburns showed up armed to the teeth at the Montgomery County Courthouse, as Deputy Dave Rusk related in the August 3, 1888, edition of the Fort Smith Elevator.

Much like officers today, the murder of one of their own had Judge Isaac C. Parker’s force of deputies out for blood. Pressure was put on the county to form another grand jury, and this time it indicted Franklin and Fayette. Despite the indictment, Franklin remained free for seven months, perhaps due to the threat of his marksmanship and a fast horse.

Franklin’s family knew that the Hanging Judge would never give up his quest to bring Franklin to justice. In March 1889, the outlaw turned himself over to Deputy W.J. Hopper. Franklin was tried, found guilty on a conspiracy charge to murder and sentenced to two years in the Ohio State Penitentiary, along with a $1,000 fine. When asked on the witness stand if he had shot Deputy Trammel, he replied, “No, but I was a well-wisher to it.”

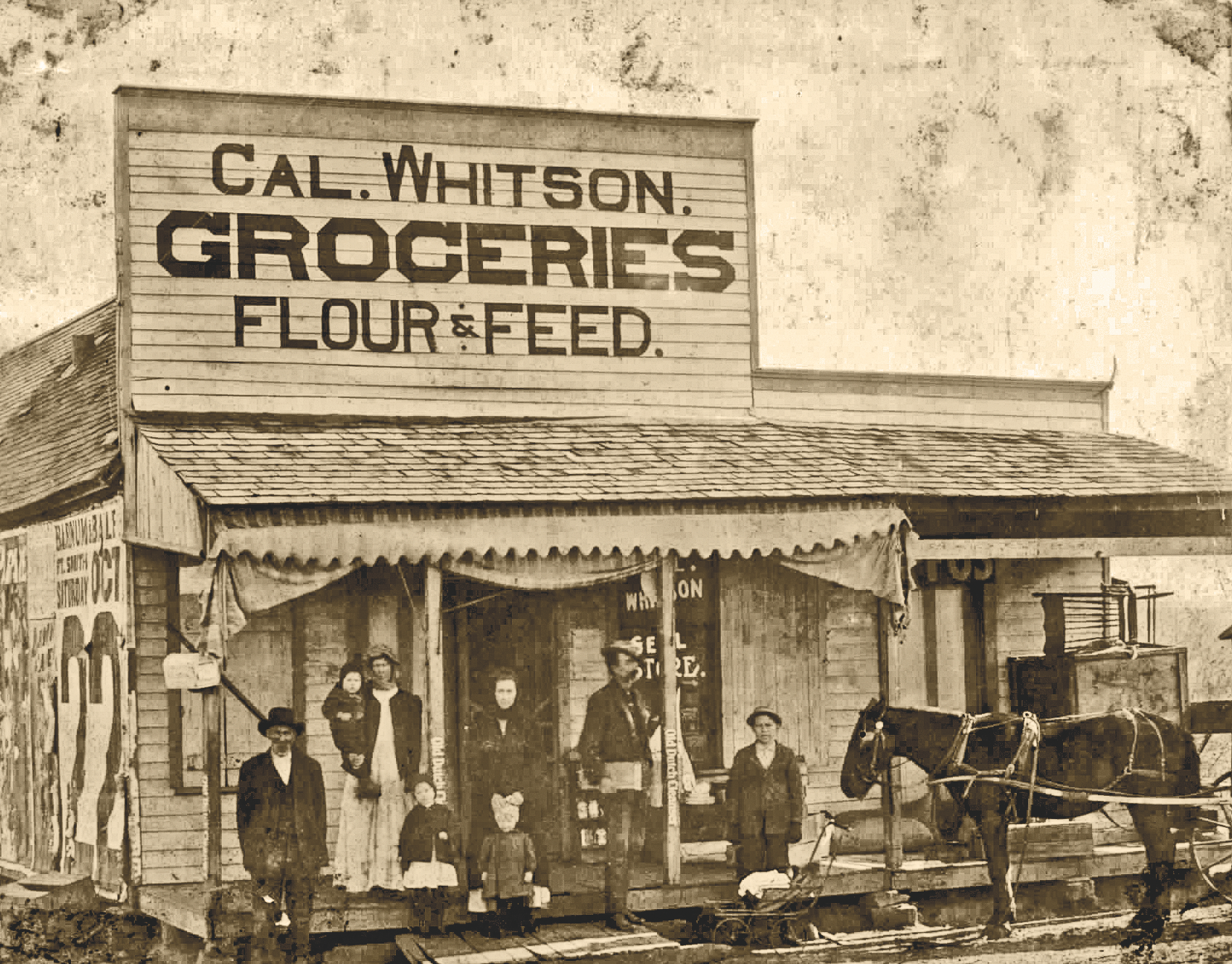

Arkansas newspaperman Charles Portis scattered in his True Grit novel bits and pieces of real Indian Territory lawmen and outlaws—John Franklin Cogburn, Deputy Reuben M. Fry, one-eyed Deputy Marshal Cal Whitson, Joseph Peppers (Lucky Ned), Joseph Spurling (Mattie’s grandfather) and Henry Starr’s bank robbing accomplice Frank Cheney (scar-faced Tom Chaney). Portis has asserted his iconic deputy marshal is a collage of different men, but a Rooster Cogburn really existed.

His name was John Franklin “Rooster” Cogburn, with two good eyes and a tale all his own.