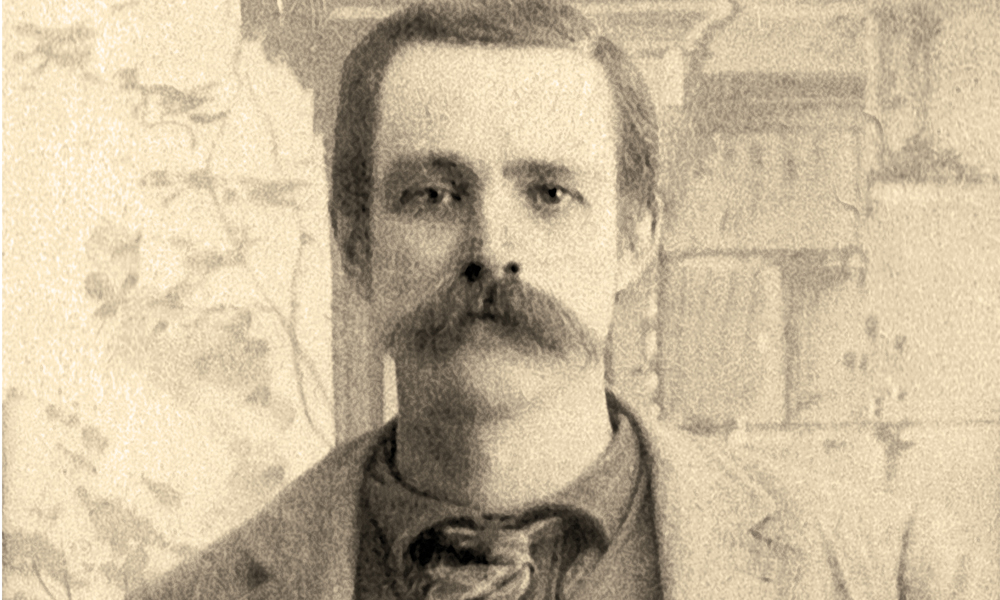

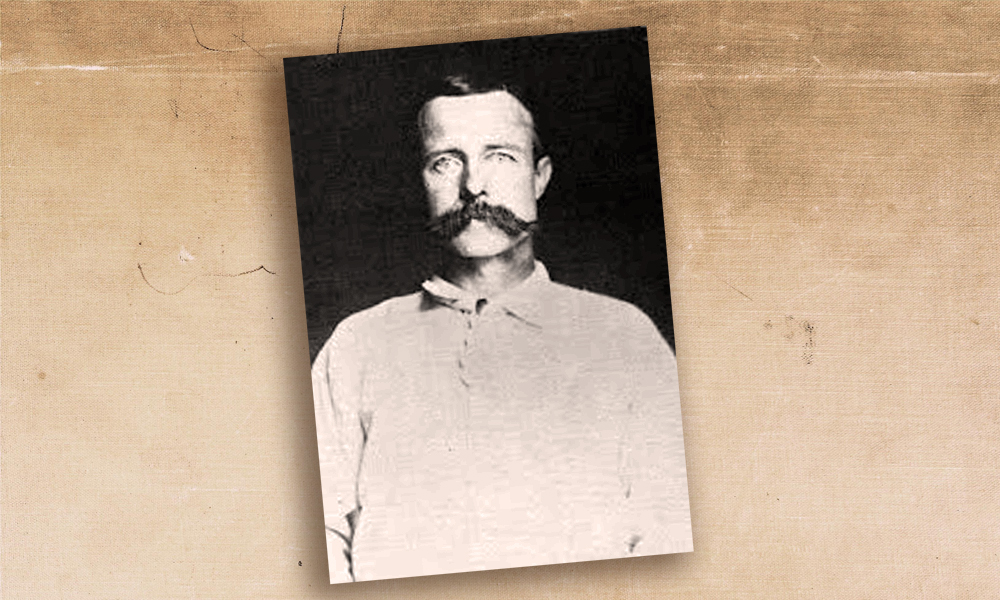

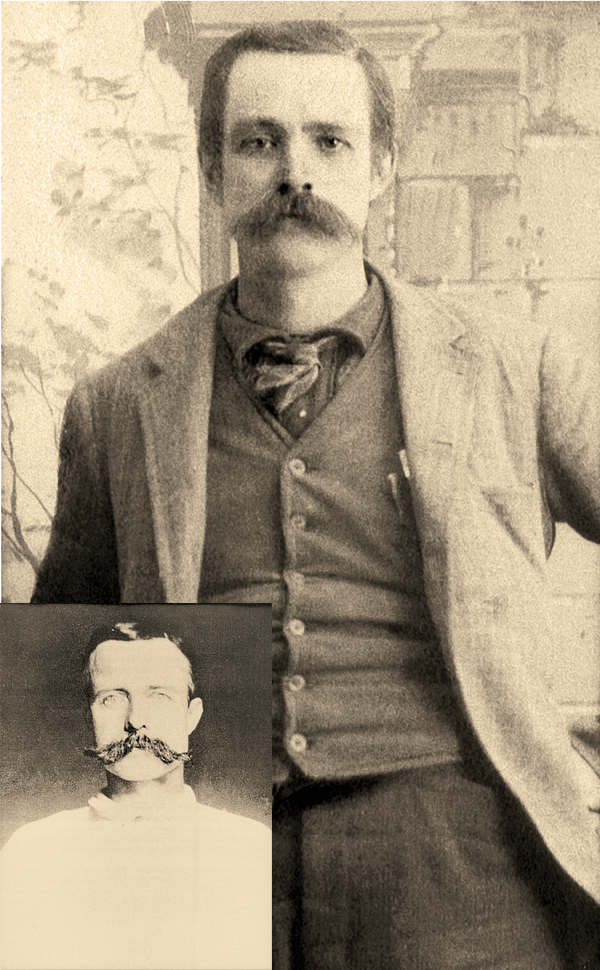

“I, Nashville Franklyn Leslie, was born near San Antonio, Texas on the 18th day of March 1842 and am now a resident of Tombstone, Arizona and have been a resident of Arizona for nine years.”

Written in a job application on March 10, 1886, these words are the earliest record of the birth date and place for the man history remembers as “Buckskin Frank” Leslie. His first 36 years prior to that record has proven elusive for researchers. Herein reveals new information that has come to light about the gunfighter who earned infamy in Tombstone, Arizona Territory.

Leslie Enters Frontier History

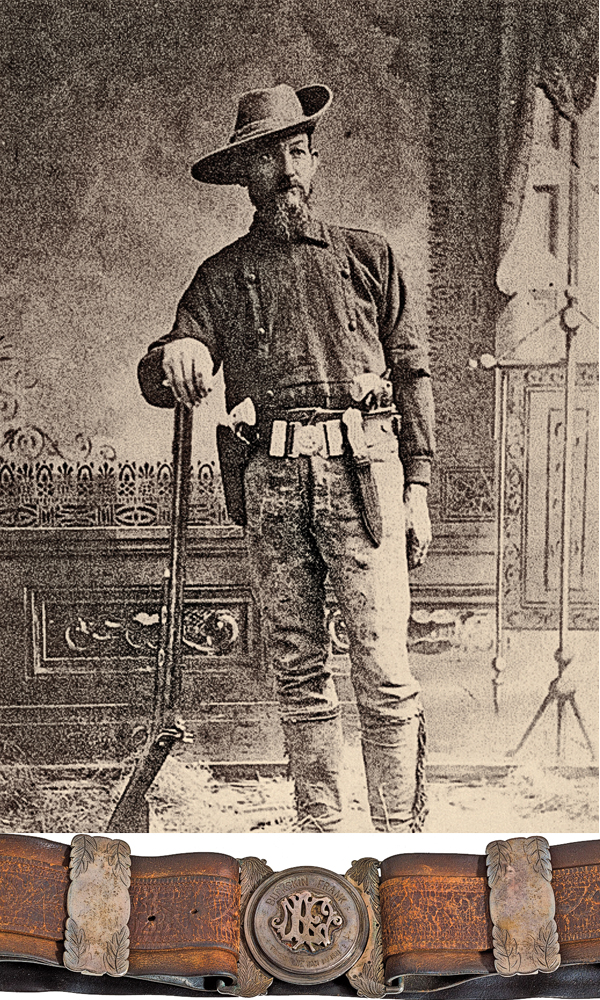

Standing five feet seven and weighing about 135 pounds, Leslie cut a dashing figure when he complemented his city attire with a fringed buckskin vest. He arrived in Tombstone in 1880, after leaving San Francisco, California, where an 1878 city directory recorded him working as a “barkeeper” in Thomas Boland’s saloon.

A new journal, Arizona Quarterly Illustrated, published a highly imaginative account of his early life in July 1880. Leslie told the journalist he was a Texas native who joined the Army in 1861 until he, a first lieutenant, surrendered on April 9, 1865, with the 10th Texas Cavalry. He then worked as an Indian scout, known as “Buckskin Frank.” From 1871-73, he served as a deputy sheriff in Kansas in Abilene and Ellsworth under James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok. He played cowboy as a rough rider in Australia, piloted a ship in the Fiji Islands and exhibited as a rifle shootist all over the world.

In Tombstone, he and William H. Knapp opened the Cosmopolitan Saloon, located next to Carl and Albert Bilicke’s Cosmopolitan Hotel. A wedding Leslie witnessed, on April 13, 1880, between the hotel’s chambermaid, Mary Jane “May” Evans, and Michael D. Killeen, would bring him trouble.

Something caused the newlyweds to separate. Mike, believing Leslie was paying too much attention to his estranged wife, came looking for him on June 22. Leslie and Mrs. Killeen were sitting on the front porch of the Cosmopolitan Hotel, following a night on the town, when George M. Perine yelled to Leslie that Mike was approaching. The warning came almost too late. Mike fired two quick shots—both of which grazed Leslie’s head.

Mike sprang upon the dazed Leslie and began clubbing him with a revolver. Leslie’s ordeal came to an abrupt end when Mike was mortally wounded. The question was: Who fired the shot?

Leslie testified that he killed Mike in self-defense. In his deathbed statement to E.T. Packwood, however, Mike said Perine had fired the shot. Although Perine was charged with the murder, the jury believed Leslie’s self-defense claim and neither party was found guilty of the crime.

On July 6, 1880, a respectful interval of eight days after her husband died, the widow Killeen married Leslie at the Cosmopolitan Hotel. For the second time, in less than 90 days, Louisa, Carl’s daughter and Albert’s sister, served as maid of honor for the bride.

Friends No More

When a fire swept Tombstone on May 26, 1882, Knapp & Leslie’s saloon was among the many buildings destroyed. The partners decided against rebuilding, and Leslie took a job bartending at the still-standing Oriental Saloon. He was working there when he became the last man standing in one of Tombstone’s celebrated gunfights.

On November 14, his friendship with 22-year-old Billy Claiborne ended suddenly and violently. Leslie had kicked out Claiborne for talking abusively to saloon patrons. Hearing that Claiborne waited outside to kill him, Leslie stepped out to sway Claiborne, who responded by aiming his Winchester at the bartender. Leslie returned fire and killed him.

On that day, Leslie was supposed to be heading to the Dragoon Mountains with George W. Parsons and others. The trip got canceled when a horse Parsons had bought from a rancher was not delivered on time.

In his diary entry, Parsons noted: “Frank Leslie was to go with us and may yet, if he is not detained in the killing matter of this morning, and he ought not to be. He shot and killed the notorious Kid Claiborne this a.m. at 7:30, making as pretty a center shot on the Kid as one would wish to…the Kid has gone to Hell. I say so because, if such a place exists and has bad men, he is there, as he was a notoriously bad egg and has innocent blood on his head. I state facts. Frank has done the country a service, and for that reason it is well that we did not get away sooner…. Frank didn’t lose the light of his cigarette during the encounter. Wonderfully cool man.”

A coroner’s jury concluded Leslie had acted in self-defense.

Later that year, Milton E. Joyce sold out his share in the Oriental and partnered up with Leslie in a ranching venture near the Swisshelm Mountains. Called the Magnolia, the Leslie-Joyce ranch was located 19 miles from Tombstone in a desolate stretch where Apaches still presented a threat to settlers, as Leslie found out on March 25, 1883, reported by the Los Angeles Daily Herald three days later:

“Yesterday Capt. Charles Young arrived from the Swisshelm’s and reported that a fight between five Apaches and himself and Frank Leslie, alias Buckskin Frank, took place on Sunday last. Leslie was surprised half a mile from camp but, after a running fight, succeeded in reaching the house. The Indians laid siege to the house and kept up a steady fire from behind rocks all afternoon. The Indians set fire to the grass in order to burn them out. Young is positive that several were killed, but following the usual custom of Indians, they either buried the killed or carried them away.”

The Magnolia Ranch venture was successful enough for Joyce to sell Leslie his share in 1885. Joyce moved to San Francisco, California, where he opened Café Royale with James W. Orndorff, a man who played a role in Leslie’s final years.

Leslie’s peaceful interlude at the Magnolia Ranch ended when several Apaches, led by Geronimo, bolted from the reservation. On May 20, 1885, Leslie signed on as a scout for the 4th Cavalry. He served until June 21, and he returned to his ranch.

Scout’s Honor?

In 1886, Leslie worked as a mounted inspector, patrolling the U.S.-Mexico border and, apparently, also moonlighting as a U.S. Army scout. “Mr. Leslie was for many years Chief of Scouts, and is in the confidence of General Crook, and is personally acquainted with Geronimo and other leading chiefs. He has just arrived from the camp of the hostile prisoners, at White’s ranch. He had a long conversation with the hostiles who have been on the warpath all summer; also with General Crook and staff,” the San Francisco Chronicle, on April 3, reported of his appearance in Tombstone.

The news account infuriated Los Angeles Times reporter Charles Lummis, who wrote a blistering broadside, headlined “Scouts and Liars,” which reported: “It is the prime ambition of [Leslie’s] existence to figure as a scout—and a scout he will be, if wild-cat dispatches from Tombstone can make him one. He was for a few weeks connected with Capt. Crawford’s command, hunting Geronimo, but was directly discharged because of his inability to tell a trail from a box of flea powder. Therein lies his claim to distinction as a celebrated scout.

“But though no scout, he is no dude. He has killed two men, under circumstances of Arizona propriety, is a fine shot, and can ride farther and harder in a day than any other white man you can rake up with a fine toothed comb.

“As to his ‘enjoying Gen. Crook’s confidence,’ I guess it isn’t necessary to say anything—but you ought to have heard the quiet old General laugh when I showed him that dispatch. Well, so much for that sort of news fodder.”

Lady Killer

On June 3, 1887, Leslie was divorced. May charged that her husband had beaten her and had an affair with “Miss Birdie Woods.” May received a settlement of $650, legal fees and a one-fourth interest in the Magnolia Ranch.

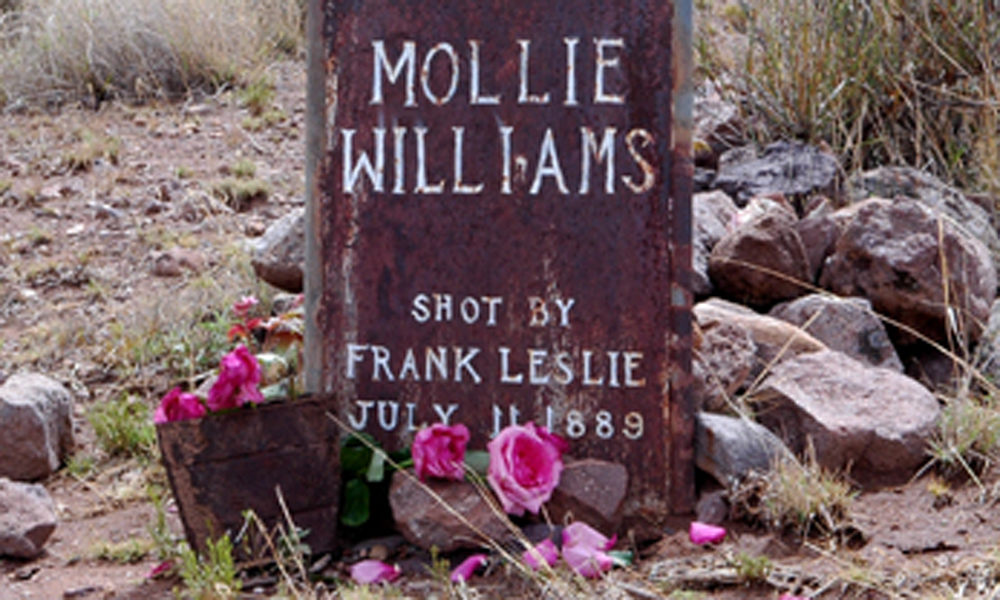

Leslie did not lack for female company following his divorce. Mollie Edwards moved in at his ranch as his “wife.” Their relationship ended on July 10, 1889, when Leslie brought new meaning to his reputation of being a “lady killer.”

When Leslie found his lover talking with James Neil, he fired shots at the pair. Neil escaped and lived to tell the tale. On January 6, 1890, Leslie pleaded guilty to Edwards’ murder and Neil’s attempted murder.

Sentenced to life, Leslie logged in as convict No. 632 at the prison in Yuma. In under three months, he joined five convicts in an escape attempt. “He had almost dug his way out but one of the convicts who was a party to the scheme weakened and notified a guard,” The Arizona Daily Citizen reported on March 31.

Three years later, the prison superintendent called Leslie, who worked as the prison pharmacist, the “best-behaved prisoner.” The San Francisco Chronicle article sharing that news encouraged 36-year-old divorcée Belle Stowell to correspond with Leslie and campaign to have him pardoned.

On November 17, 1896, Gov. Benjamin J. Franklin granted Leslie’s pardon. Leslie took a train to Stockton, California, where he and Stowell got married on December 1. The following day, the Stockton Daily Independent reported their nuptials and observed that the newlyweds planned to honeymoon in China. They never caught that steamer.

Their next press notice, in the San Francisco Call, reported that Stowell was the “ex-wife of a prominent man in the employ of the Southern Pacific Railroad Company.” The former husband had sent a detective to obtain evidence of the marriage, so he could have alimony revoked.

Instead of the detective catching the two, Leslie and Stowell separated. They officially divorced seven years later.

Back on the Trail

Free of his paramour, Leslie looked up John Ralph Dean, who had employed him at the Fashion Saloon in Tombstone, Arizona Territory. Dean was the night manager of the Delaware Café inside the Delaware Hotel in Fort Worth, Texas. A local newspaper noted their reunion on April 7, 1897.

Leslie was still living in Fort Worth on January 17, 1898, when he made plans to prospect for gold in Alaska, but he never got there. An April 1898 news account recorded him in Hermosillo, Mexico, with a friend from his Tombstone days, Dr. George Goodfellow. Leslie could not have stayed long in Mexico, if his claim is to be believed that he enlisted, fought and was wounded in the Spanish-American War.

Following his alleged war service in Cuba, Leslie moved back to Tombstone, in August 1898, to guide surveyors to the La Barranca coal fields: “A party of engineers under Prof. E.T. Dumble engaged in making a geological survey of Sonora and this section of Arizona for the S.P. Railroad Company arrived in town today and among the party is Frank Leslie, who is acting as guide. Leslie, although now nearly 60, carries his age well and is claimed by acquaintances that he looks as natural as ever. Since leaving Arizona Leslie has been in Cuba and returned wounded. After recovery he joined this surveying party and it is expected they will be engaged hereabouts for several months,” Phoenix’s Arizona Republican reported.

The Two Geronimos

Leslie returned to California for the Christmas holidays, The Oasis reported on December 16, 1899. Three days later, Maj. Gen. Henry Ware Lawton was killed in the Philippines. The San Francisco Call gave a full page to Leslie’s article about Lawton on January 7, 1900:

“My work with General Lawton commenced with a chase after one Geronimo, and was ended by another Geronimo of another race, on the opposite side of the earth. I knew Lawton when he was a private fighting his way through more than thirty battles of the Civil War from the ranks to a commission. I was his chief of scouts when we walked and climbed 800 miles through the Sierra Madre. I was with him in Cuba, and had been asked to take a place on his staff in the Philippines when he was killed in his engagement with General [Licerio] Geronimo…. His death leaves me thinking of things of which I would care not to speak. I can only think of the two Geronimos, one the last of his race to submit, the other the last leader of organized troops in the Philippines, and the life of Lawton between.”

Leslie’s Last Shooting

By the turn of the 20th century, Leslie participated in his last documented shooting.

“After many years spent on the frontier as a Government scout Frank Leslie fell a victim to his own pistol early yesterday morning…while in a saloon at Market and Ellis streets, he stooped over, the weapon fell out of his pocket, fell to the floor and was discharged,” the San Francisco Chronicle reported on November 25, 1902.

“The bullet struck him about four inches above the knee, passing through the fleshy part of the leg, tore his right ear and cut a gash in his scalp…. ‘I suppose,’ said Leslie, ‘that my friends will tell me I’m not fit to carry a pistol. After forty years on the frontier to be hurt by my own gun, looks like it.’”

Leslie survived his fumbled shot.

After San Francisco’s earthquake and fire of 1906, Leslie moved to Berkeley. He met 43-year-old Elnora Tolbert and married her, in Napa, on November 6, 1913. This marriage certificate included Leslie’s identification of his parents: his father, Bernard Leslie, born in Virginia, and his mother, Martha Leslie, born in Kentucky.

The new Mrs. Leslie convinced her husband to move to Omak, Washington. She remained in Omak until her dying day. Leslie lived there about two years. Still as footloose as ever, at age 74, Leslie was interviewed in Seattle on May 20, 1916, concerning a mining trip in Mexico that he was planning.

The 1920 census recorded Leslie living at 959 Water Street in Sausalito, California, a home owned by Orndorff, who knew Leslie’s former business partner Joyce. In the next census, Elnora is listed as “widowed.” We do not have Leslie’s death record, but he does not appear on a 1930 census.

A Hollywood Ending?

One document suggests Leslie might have been alive as late as September 9, 1923. On that date, Dean wrote actor William S. Hart to recommend Leslie as a technical advisor for Hart’s film, Wild Bill Hickok.

Dean mistakenly advised Hart that he could find Leslie at Orndorff’s billiard parlor in Berkeley when it was located in Sausalito. Plus, Orndorff had died seven months earlier, on February 16. Hart probably did reach out to Leslie, since the actor was known for forming friendships with Old West icons Bat Masterson and Wyatt Earp, but no record proves they touched base.

Resolving the mystery surrounding the bartender-turned-gunfighter’s death would hardly close the book on Leslie. From his birth in 1842 until he turned up in San Francisco in 1878, nothing is known of Leslie that has been verified. Was he a Confederate cavalryman? Did he travel to Australia and the Fiji Islands? Was he a college graduate? These claims, along with others, such as his service as a deputy under Hickok or as a scout under Gen. George Custer, appear to have been made from whole cloth.

If any among you take on the challenge of closing the gaps in Leslie’s life, you will find your search rewarding. Few characters in Wild West history were as colorful or as constantly surprising as this man.

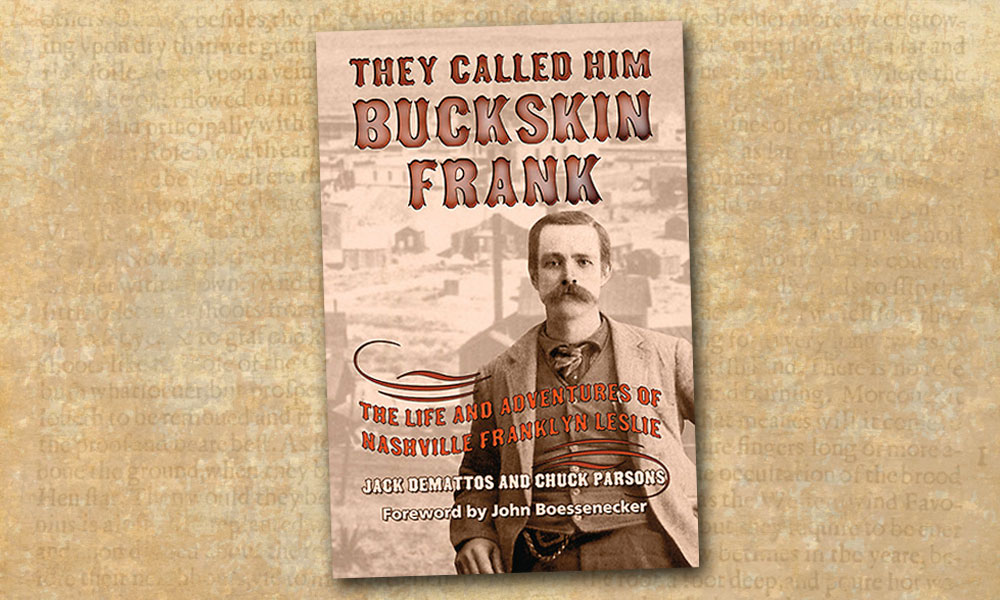

Jack DeMattos wrote his first history article, for True West Magazine, 40 years ago. After numerous publications, he received his first award in the field, in June 2016, from the Wild West History Association, for his article on Buckskin Frank Leslie.