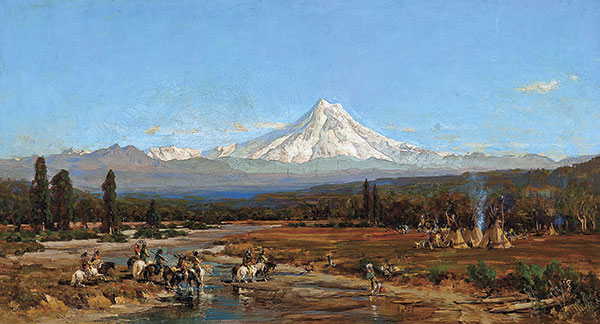

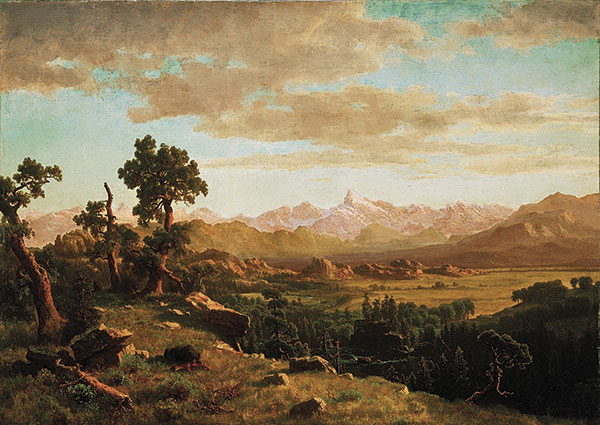

— Courtesy The Peterson Family Collection, on display in the exhibition Courage and Crossroads: A Visual Journey through the Early American West at Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West/ScottsdaleMuseumWest.org —

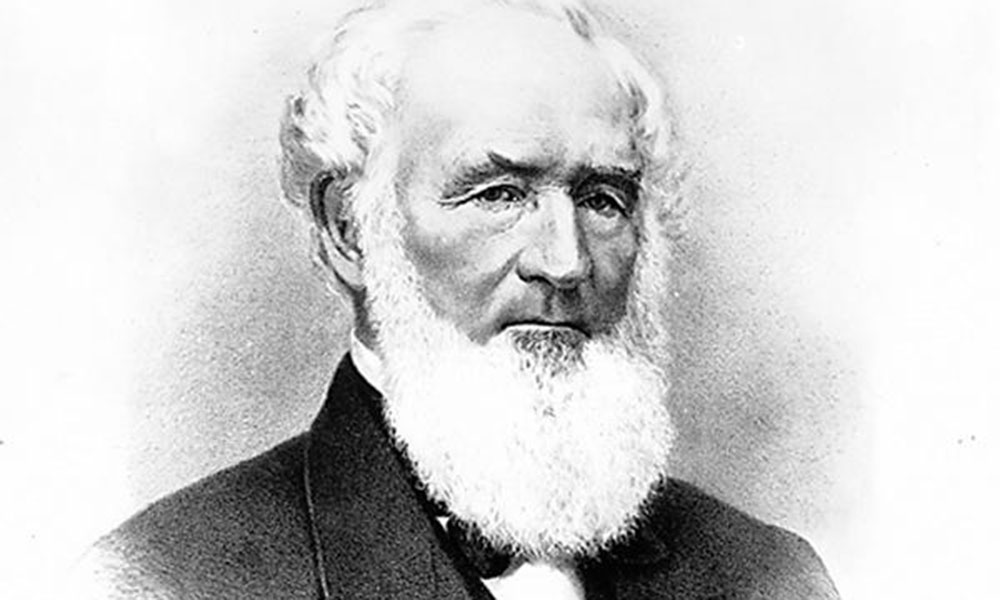

Grandeur is often associated with the paintings of early artists of the American West: George Caleb Bingham, Karl Bodmer, William Jacob Hays, Thomas Moran, Alfred Jacob Miller, John Mix Stanley and especially Albert Bierstadt.

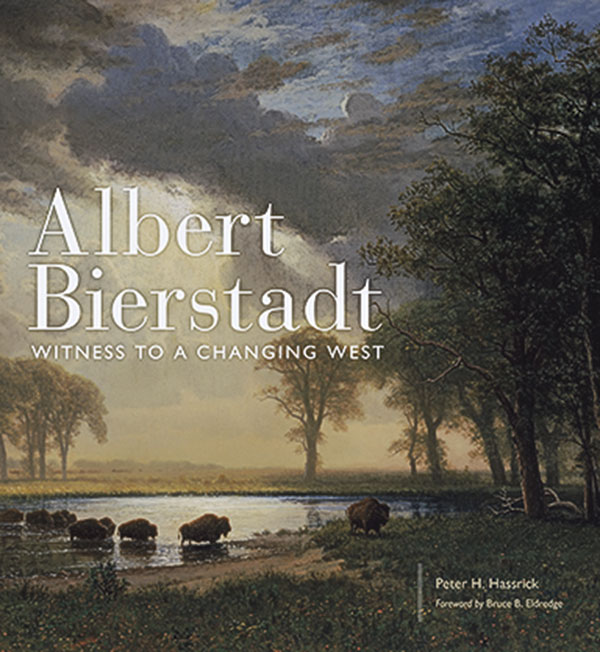

The later is the subject of a new exhibition, Albert Bierstadt: Witness to a Changing West, closing at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Whitney Western Art Museum in Cody, Wyoming, Sept. 30, 2018, before moving to the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Nov. 1, 2018 – Feb. 10, 2019. The University of Oklahoma Press has published a companion book—written by Peter H. Hassrick, director emeritus and senior scholar at the Center of the West, with contributions by other art scholars—that reappraises the career of Bierstadt (1830-1902).

— Courtesy Stark Museum of Art, Orange, Texas, Bequest of H.J. Lutcher Stark, 1965, 31.34.29 —

Bierstadt certainly illustrated the West’s grandeur, but Karen McWhorter, the Whitney’s Scarlett Curator of Western American Art, prefers another word.

“I think of awesome,” she says, “which has been used in pop culture since the ’90s for so many different things, like awe-inspiring, truly awestruck. Words to describe the Rocky Mountains and the Great Plains.”

Besides, “the grandeur and sublimity of the Western landscape is a more loaded subject than might be predicted, as the manner in which it has shaped our ideas and aspirations relies as much on fact as on imagination and projection,” says Toby Jurovics, chief curator at the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska.

— Courtesy Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma. Gift of the Thomas Gilcrease Foundation, 1955. 0126.230 —

urovics singles out Bodmer and Miller among the earliest Anglo-European artists to visit the West. “Bodmer’s careful and deliberate watercolors made along the Upper Missouri are prized for their topographic accuracy and rigorous attention to detail, while Miller’s romantic vistas became the backdrop for action and adventure. The difference in their approaches reflects the desires of their patrons—Bodmer working for the naturalist Prince Maximilian of Wied, and Miller for the Scottish nobleman Sir William Drummond Stewart—but it also encapsulates the ongoing tension between our romanticized vision of the landscape and the often unpleasant truths of Western expansion that are masked by the beauty of the Western horizon,” Jurovics explains.

— Courtesy Tacoma Art Museum, Tacoma, Washington. Haub Family Collection. Gift of Erivan and Helga Haub, 2014.6.8 —

Bierstadt might have saved his best work for his last great Western paintings, the two versions he created in 1888 of The Last of the Buffalo, an allegory for the end of the American bison and the Plains Indians’ way of life.

“If you look at the trajectory of his career, you can see the shift from a very idyllic, beautiful and peaceful West to the opposite, showing the destruction of those things in a very poetic statement,” says Laura F. Fry, the Gilcrease’s senior curator.

Art, of course, is always in the eye of the beholder.

— Courtesy Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma, GM 01.1591 —

“You won’t often find a group of dyed-in-the-wool genuine cowboys gathered at an art gallery discussing the virtues of any particular piece of art hanging on the wall,” says Brent Harris of the Boot Hill Museum in Dodge City, Kansas. “Yet most true cowboys have a deep appreciation for art.”

Besides, “cowboy” artists Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell knew a thing or two about landscapes.

Mary Burke, director of the Sid Richardson Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, points to Remington’s 1909 oil-on-canvas Buffalo Runners-Big Horn Basin. “The land is expansive, sun-struck,” Burke says, “but the human figures are in concert with the land. And in this case, there is a sense of freedom, exhilaration in the figures.”

— Courtesy the Joslyn Museum, Gift of Gail and Michael Yanney and Lisa and Bill Roskens, 2001.40.10 —

Adds Emily Wilson, curator at the C.M. Russell Museum in Great Falls, Montana: “As a master storyteller, we can think of Russell’s paintings collectively as an anthology of the

stories-so-far of the Montana landscape—its flora, fauna and wildlife—in relationship to the domestic and the human. They are an echo of its distant history, its present as painted and, for us, as a contemporary audience, its relevance today.”

Over time, Bierstadt’s interpretations of the West fell out of favor. “He didn’t keep up with trends of his time,” Hassrick says. It wasn’t until the 1960s that Bierstadt’s awesomeness began to be reassessed.

Twentieth-century artists depicted the West’s grandeur in their own styles.

“Maynard Dixon created dramatic images of the Western landscape that convey the power of nature,” says Sarah E. Boehme, curator of the Stark Museum of Art in Orange, Texas. “His imagery featured the desert landscape, a different iconography from the towering mountainscapes of Bierstadt. In the late 20th century, Wilson Hurley addressed the expansive and compelling landscapes of the American West. His use of light and his experience as a pilot bring a heightened sensibility to his representations.”

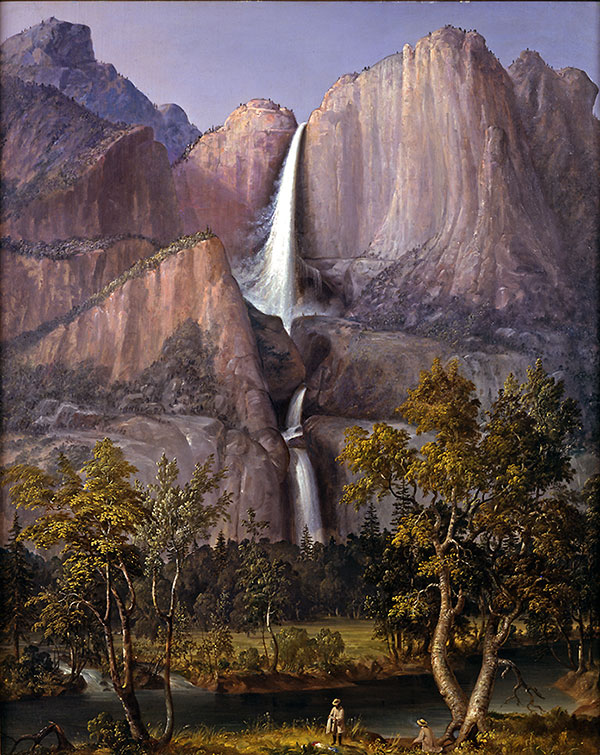

— Courtesy Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Lloyd Taggart. 2.63 —

That continues today. In Big Horn, Wyoming, The Brinton Museum recently featured a major exhibition of works by contemporary landscape artist Paul Waldum, whose influences include Moran and Yellowstone National Park.

“Waldum’s work is about the mood and atmosphere of the outdoors and using his knowledge and abilities to translate that scene onto paper for the rest of us to interact with, using our personal experiences as translators of the Wyoming and Montana landscape,” says Kenneth L. Schuster, the Brinton’s director and chief curator.

Today’s artists continue to reinterpret the West, much as Bierstadt did in the 1800s.

“There will always be an audience for landscape art that speaks to the West as a spectacular, special environment, images that set the region and its natural monuments apart from other parts of the country,” says Amy Scott, chief curator at the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles.

“The desire to look at places like Grand Canyon, the Sierras or the Rockies as emblematic of American exceptionalism is part of our cultural DNA. At the same time, artists have much greater freedom in what places they select to paint and how they paint them, whether that means abstraction or the urban West. There is a recognition, and even a celebration, in contemporary landscapes that the West is not one place, and that its experience and meaning vary depending on where you live and who you are.”

— Courtesy Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, 1966.1 —

— Courtesy Petrie Institute of Western American Art, The Denver Art Museum The Charles H. Bayly Collection, 1987.47 —

— Courtesy Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma, GM 0127.1545 —

— Courtesy Newark Art Museum, Purchase 1961 The Members’ Fund 61.516 —

— Courtesy Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West, The Peterson Family Collection —

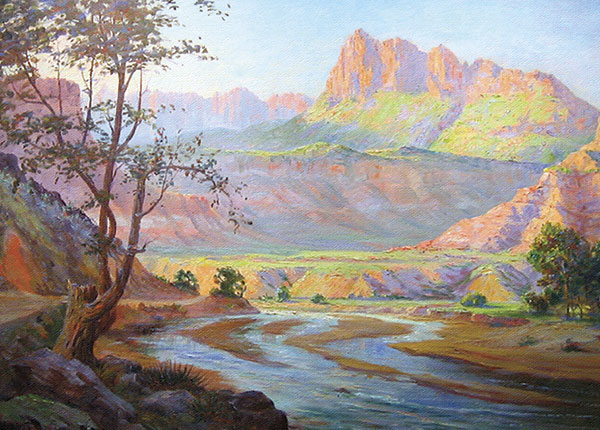

— Courtesy St. George Art Museum, St. George, Utah —

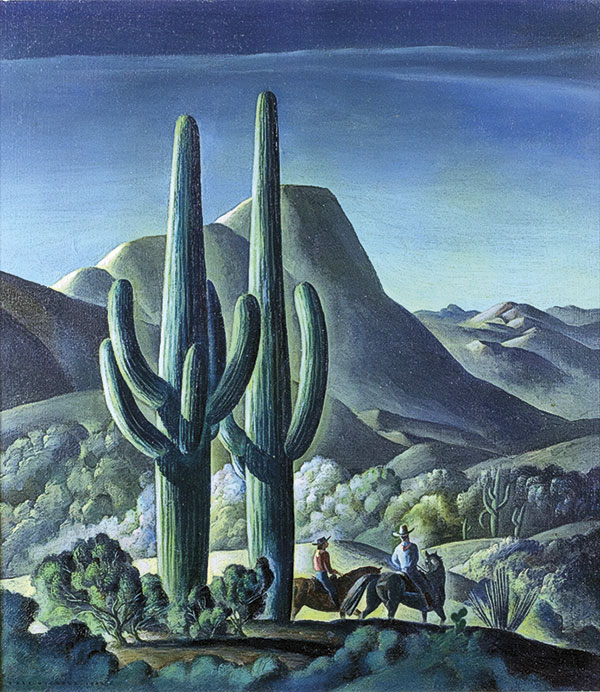

— Courtesy Tucson Art Museum —

— Courtesy Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West, The Peterson Family Collection —

— Courtesy Stark Museum of Art, Orange, Texas, Engraving on Paper, 91.121.24 —

— Courtesy Andy Thomas, Maze Creek Studios —

— Courtesy Northeastern Nevada Museum, Elko, Nevada —

— Courtesy Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art, Museum purchase through the generosity of Harrison Eiteljorg —

— Courtesy Newark Museum, Gift of Mrs. Charles W. Engelhard, 1977, 77.5 —

Peter H. Hassrick’s Albert Bierstadt: Witness to a Changing West (University of Oklahoma Press, $35), published in cooperation with the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming, is an accompaniment to the exhibition of the same name at the BBCW’s Whitney Western Art Museum and the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

For years, Johnny D. Boggs has written about art for True West and several other publications, even though he can’t draw anything awesome.

https://truewestmagazine.com/2018-wwa-spur-award-winners/