The manly art of prizefighting has been around since the beginning of recorded time, but only in the last decade has the sport been promoted into a billion-dollar industry. The evolution of boxing from a working class pastime of bare-knuckle brawling to a pay-per-view mega attraction can be traced back to two legendary lawmen from the Old West: Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson.

The seed that launched the career of the greatest showman boxing promoter in American history was planted during Wyatt’s years in Alaska.

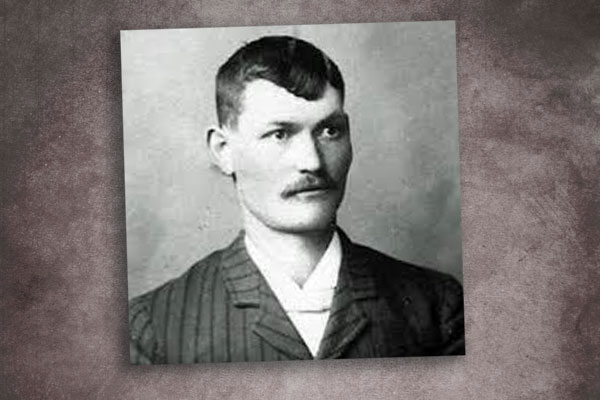

Wyatt “Referee” Earp

Wyatt arrived in Nome in the summer of 1899. By then, Wyatt had gained some fame in the boxing world—not all good.

Wyatt, in his early 20s, began officiating boxing matches across Wyoming Territory for rail crews and buffalo hunters. Before Wyatt got linked with heavyweight champion Bob Fitzsimmons, a pal of Wyatt’s, Bat Masterson, helped Judge Roy Bean promote a bout between Fitzsimmons and Peter Maher.

With boxing outlawed in Texas, the bout was fought in a makeshift ring on Mexican soil, in the town of Coahuila, with spectators viewing the fight from a hillside overlooking the Rio Grande.

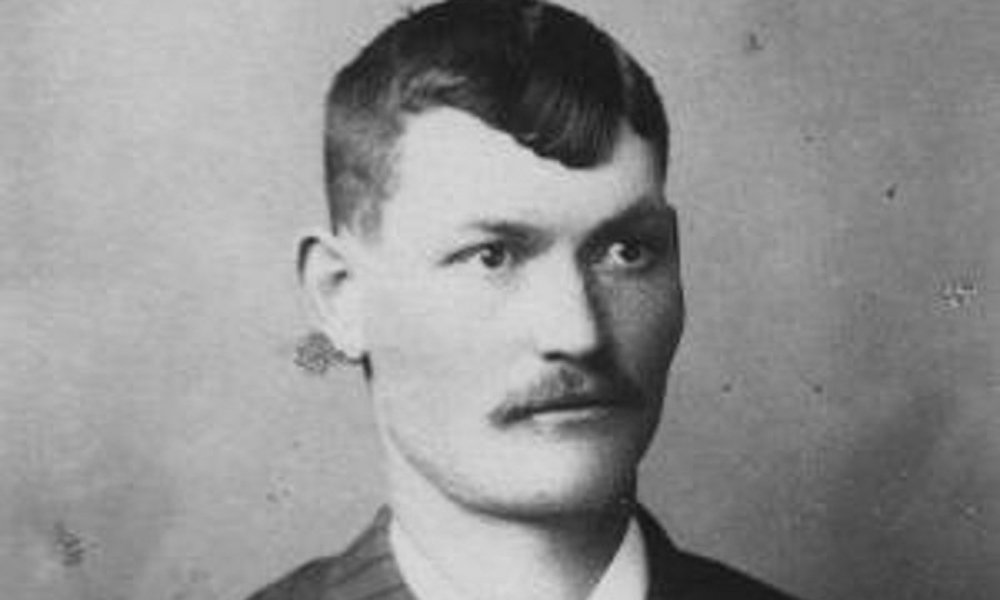

A former lawman in Dodge City, Kansas, Masterson secured the ticket handling and fight purse. He also covered the sport in his Denver, Colorado, newspaper column for George’s Weekly and promoted prizefights at his Olympic Athletic Club.

Masterson’s history in the boxing arena included serving as the timekeeper at the first World Heavyweight Championship, under the Queensberry Rules. In the 1892 battle, “Gentleman Jim” Corbett defeated “Boston Strong Boy” John L. Sullivan by knockout in the 21st round.

In the 1896 bout in Mexico, Fitzsimmons scored a knockout win in 95 seconds. Masterson moved on along the boxing circuit.

Later that year, a scandal erupted.

In a San Francisco, California, heavyweight contest, Fitzsimmons landed a three-punch combination on “Sailor Tom” Sharkey, with the last punch hitting below the belt. Wyatt ruled the final blow a foul and awarded the fight—and its $10,000 purse—to Sharkey.

A friend of Sharkey’s manager Danny Lynch, Wyatt was accused of fixing the fight, a claim he denied. He dissuaded the embittered Fitzsimmons and the angry crowd from seeking revenge by exiting Mechanics’ Pavilion with his trusty Colt .45 in his hand.

— Courtesy Jeff Morey —

The Dawson Seed

Hoping to find some of the gold glittering on the shores of Nome, Alaska, Wyatt arrived there with his wife, Josie. He had been invited by a friend, George Lewis “Tex” Rickard.

Born in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1870 and reared in north Texas, where he worked as a city marshal in Henrietta, Rickard had rushed to Alaska during the gold strike of 1895. He staked claims for two, hapless years until the Klondike discovery of 1897 pulled him into the greatest stampede in American history.

A move to Dawson marked the beginning of Rickard’s “golden touch.” Within a year, his claims had paid close to $60,000. He parlayed his prospecting success into purchasing a thriving saloon, the Northern. Yet his eagerness to multiply his fortunes got the best of Rickard. He gambled away his business in Dawson’s “emporiums of chance.”

When Rickard struck pay dirt yet again, he poured his earnings into a newer Northern, the largest saloon in Nome.

Wyatt and Josie had previously tried their luck in the Yukon in 1897. They made it as far as Juneau, Alaska, before turning back, reportedly because Josie was pregnant (she later miscarried).

The next year, they made it to Wrangell, where bad weather forced them to hold up until the spring thaw. By the time they moved on to Rampart, the Klondike Rush was all but over.

After arriving in Nome in 1899, Wyatt introduced Rickard to the lucrative enterprise of live boxing shows, thus launching the career of one of America’s greatest sports promoters

and ballyhoo artists.

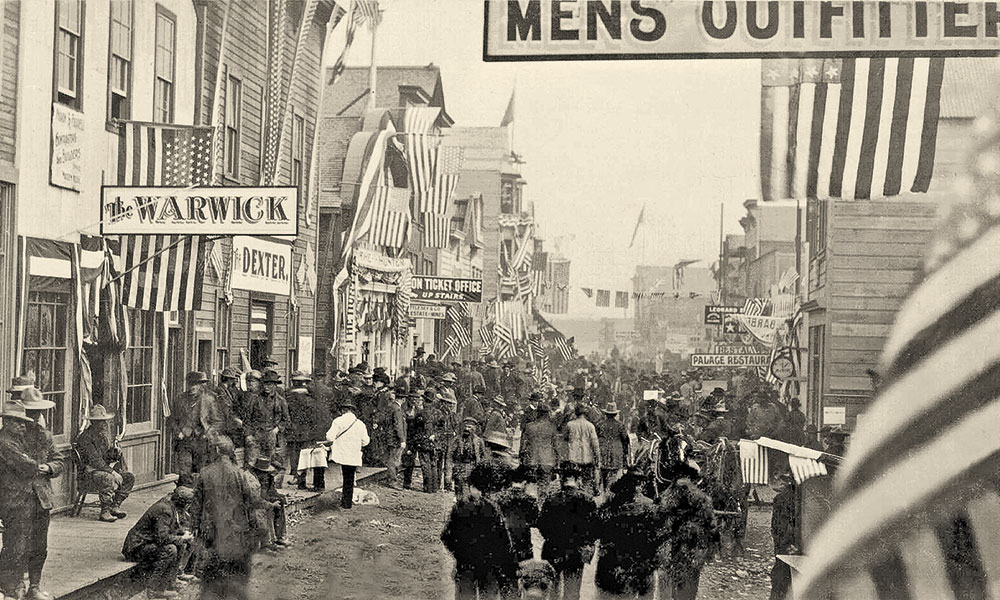

Like his pal, Wyatt gambled on the saloon business, building the Dexter Saloon with C.E. Hoxie (also spelled Hoxsie), which opened in September. Wyatt’s fame as a gunslinger drew business. After two years, he sold his interest in the Dexter to Hoxie and transferred his mining claims to Josie’s brother, Nathan.

Wyatt and Josie boarded the SS Roanoke for Seattle, Washington, with $80,000 (more than $2 million today). They moved to Tonopah, Nevada, where Wyatt ran a saloon and worked as a deputy U.S. marshal.

— Courtesy F. Daniel Somrack —

Goldfield’s World Title Fight

Rickard followed the Earps a few years later, landing south, in Goldfield, when the Silver State’s boomtown was in full swing. With the 1902 strike, the mining camp’s population soared from a few scrub prospectors to 20,000 souls, making it Nevada’s largest town.

Rickard opened the last and largest of his Northern saloons.

Goldfield is also where Wyatt’s brother, Virgil, lived out his last days. After arriving in 1904, he was sworn in as deputy sheriff of Esmeralda County. With his left arm maimed and rendered useless by the O.K Corral shoot-out in Tombstone, Arizona Territory, Virgil took a job as a security officer at the National Club saloon. Struck by pneumonia, he died on October 19, 1905.

Rickard found a distraction for Wyatt as he grieved his older brother’s death. Rickard announced on the news wire that Goldfield wanted to host a world title fight. The first boxer to accept Rickard’s challenge was the number-one contender for the lightweight crown, Oscar “Battling” Nelson.

Rickard needed to raise $30,000, so he could sign Joe Gans, the country’s first black lightweight champion. With the help of con artist and criminal stock trader George Graham Rice, Rickard secured the funds within days.

Rickard stacked the purse’s $10 and $20 gold pieces in the window of the local bank. A staggering sum at the time, the trick put Goldfield in headlines nationwide.

Held on September 3, 1906, the mixed-race match-up became the longest bout of the century. Gans outfought the “Durable Dane,” winning on a foul in the 42nd round. The sold-out, 20,000-seat event paid $69,715 ($1.92 million today).

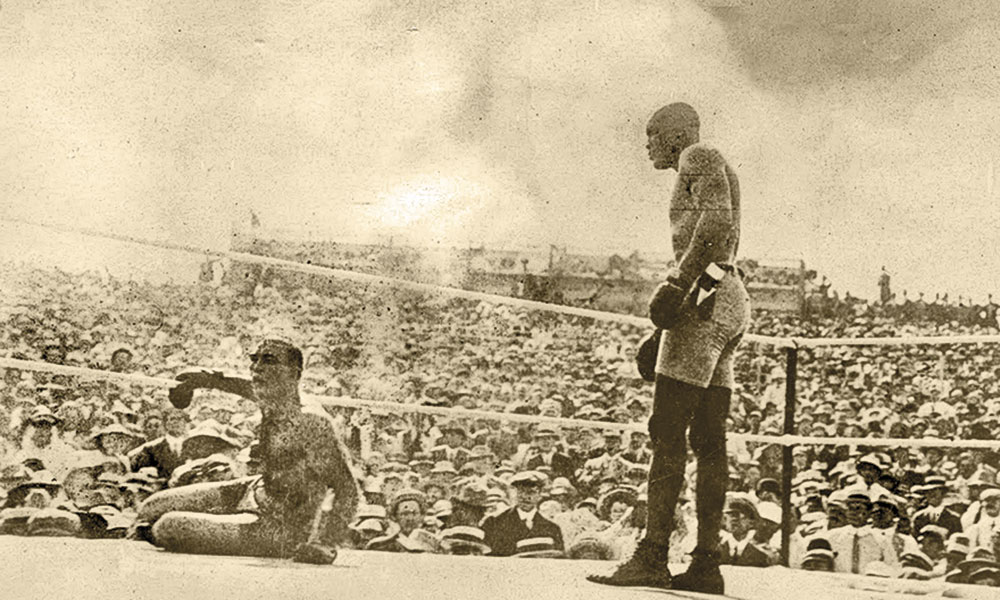

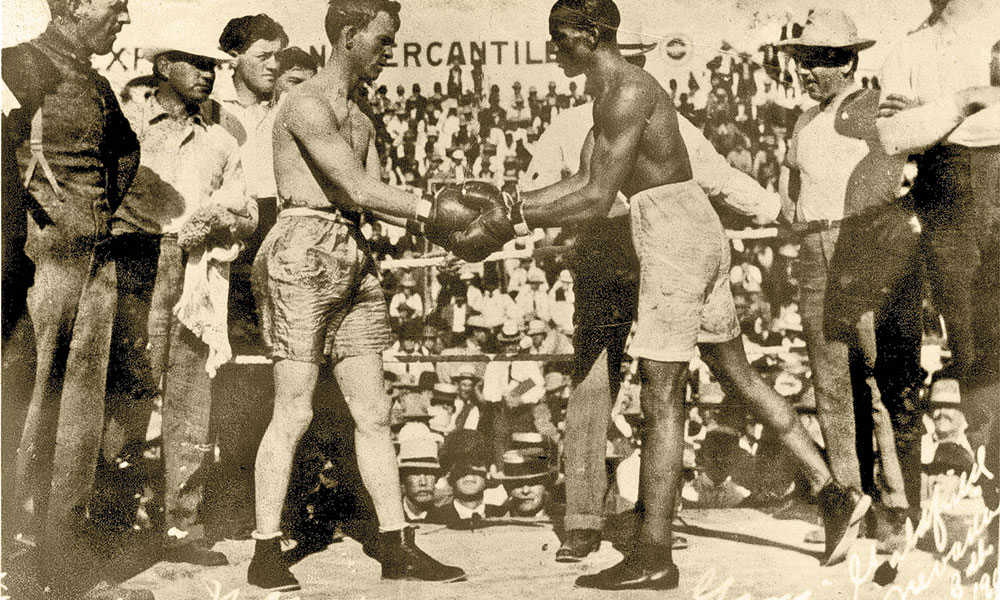

Rickard’s next “main event” was Jack Johnson versus James J. Jeffries in Reno. Billed as the “Fight of the Century,” this July 4, 1910, heavyweight contest paid out an unheard of sum of $120,000 ($3.13 million today) to Johnson so he would defend his title against the undefeated Jeffries. Lured out of his six-year retirement with a guaranteed payout for $60,000 ($1.56 million today), Jeffries got knocked out in round 15.

When Johnson was defeated by Jess Willard in Havana, Cuba, on April 5, 1915, Masterson reported on the fight for the New York Morning Telegraph.

Willard wore the crown until 1919, when he was crushed in three rounds by “Manassa Mauler” Jack Dempsey. The Rickard-promoted event launched the Roaring Twenties and the Golden Age of boxing in America.

— Saloon photo Courtesy Carrie M. McLain Museum collection —

Boxing for the Bluebloods

When New York legalized boxing in 1920, Rickard moved his promotional operations to Manhattan. By then, Rickard and Masterson were respected members of New York’s high society and friends of the Astors, Rockefellers and Roosevelts. They strolled the sidewalks of New York with their trademark Fedora and Stetson hats and gold-handled walking sticks.

Rickard’s first “million-dollar gate” took place on July 2, 1921—the bout between Dempsey and Georges Carpentier. More than 90,000 hysterical fans paid $1,789,238 to watch Dempsey demolish the Frenchman in four rounds. The fight was the first major radio broadcast of a sporting event.

Dempsey’s was also Masterson’s last heavyweight championship fight. He died, on October 25, of a heart attack, after writing a column for the New York Morning Telegraph. Roughly 500 people attended Masterson’s funeral; Rickard served as a pallbearer.

The sport of boxing kept punching on. Rickard assembled financial backers he called the “600 millionaires” and constructed a third edition of New York’s Madison Square Garden. The “house that Tex built” opened on Eighth Avenue in December 1925. The modern setting made it fashionable for ladies and bluebloods to attend boxing matches.

The boxing impresario also expanded his sports empire; he bought a NHL hockey team for the 1926–27 season. His Rangers, later the New York Rangers, won the division title in their debut season and the Stanley Cup in their second year.

Throughout the 1920s, Rickard’s adept manipulation of the press continued to produce million-dollar gates at the box office. The Jack Dempsey-Gene Tunney championship rematch at Chicago’s Soldier Field generated a record $2,658,660 ($37.5 million today).

— Courtesy Chapman University Digital Commons —

Boxing’s First Champion

Recognizing the profit potential in a year-round resort community like Miami Beach, Rickard went to Florida on January 1, 1929, to evaluate opportunities. After a bout of appendicitis, he died one week later, at age 59.

Before hearing the news of his pal’s death, Wyatt got out of his sick bed to send Rickard a get-well telegram, caught a chill and relapsed into chronic cystitis. The frontier lawman died one week later, on January 13, at age 80.

Rickard’s body was brought to New York’s Madison Square Garden to lie in state in a $15,000 bronze casket. Thousands of mourners said their goodbyes to the man who had risen from a humble Texas lawman into an empire builder. One of the last links to the great American heroes of the Old West, the trailblazing visionary had made boxing the mega sport it is today.

F. Daniel Somrack is a filmmaker and boxing historian who produced the sports documentary, Champions Forever, featuring Muhammad Ali, Joe Frazier and George Foreman. He is also the author of Boxing in San Francisco. Head to BoxingScribe.com to read his blogs.

https://truewestmagazine.com/boxing-impresario-nonpareil/