— Courtesy Library of Congress —

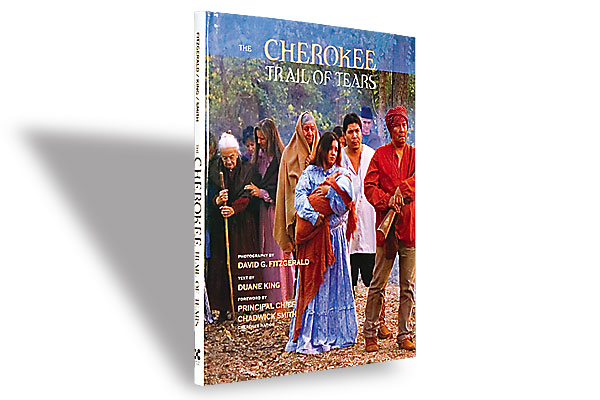

Before the forced removal of Cherokees from their tribal lands between 1836 and 1839—the so-called “Trail of Tears”—another tribe, the Seminoles, bitterly fought relocation.

The Seminole Trail of Tears tracks to 1817, when U.S. troops invaded tribal lands in Spanish-owned Florida, looking for escaped slaves. Troops led by Gen. Andrew Jackson destroyed Seminole villages and crops. The general would be a thorn in the side of the tribe in coming years, especially after Florida became U.S. property in 1819.

The Treaty of Moultrie in 1824 established a Florida reservation for the Seminole, but many lived in their home areas instead. White settlers who wanted the Seminole land pressured the government to remove the tribe.

Settlers gained a strong supporter when Jackson was elected president in 1828. He sought to relocate the tribes to Indian Territory, a largely unoccupied area west of the Mississippi River. The move was part of Congress’s Indian Removal Act in 1830.

The Seminoles initially agreed to move west, approving the Treaty of Payne’s Landing in 1832, but they changed their minds. They just could not get over the idea of living on the same reservation as their longtime enemies, the Creeks. They decided to take their chances and fight for their home in Florida.

Troops moved into Florida to enforce the treaty. By the end of 1835, fighting had broken out. Who started it is still a matter of debate. Over the next seven years, each side claimed victories in battle. But the Seminoles were outnumbered and out-armed. Supported by the Marines and Navy, U.S. troops made headway in sending Seminoles west. Government negotiators sometimes tricked Seminole leaders to meet for talks, only to take them into custody and relocate them.

Some Seminoles took refuge in the swamps and Everglades, challenging areas where whites couldn’t find them. By 1843, the remaining Seminoles were told they could settle on an informal reservation in Florida. Not all moved. The government was tired of fighting and understood the impossibility of relocating all the Seminoles.

The relocation effort was costly. The U.S. spent between $30 million and $40 million during the second Seminole War, estimates John K. Mahon, author of History of the Second Seminole War, 1835-1842.

Of the approximately 40,000 troops who participated, nearly 1,500 died—most from disease. History does not record how many Seminoles perished during the conflict.

All that money and lives to resettle 3,824 Seminoles to Indian Territory. In November 1843, fewer than 3,000 remained on a reservation in southwest Florida. But U.S. pressure to remove the tribe continued, leading to another war in the late 1850s.

After that war, the government paid Seminoles to relocate, and hundreds did. But many others hunkered down in the swamps and marshes, refusing to leave Florida. Some descendants still live there.