There was no shortage of ways to go to the “go under” in the Far West during the heyday of the Mountain Men. In 1856 Antoine Robidoux could account for only three out of three hundred who went into the Rockies some thirty years earlier. James Ohio Pattie recalled only sixteen survivors out of one hundred sixty men in only one year on the Gila watershed in Arizona and New Mexico. If the trapper didn’t get his topknot lifted or worse by Indians there were many other ways to go to the “long sleep.”

Grizzly bears were numerous and had no fear of man. Trappers reported seeing as many 220 in a single day and as many as fifty or sixty in a bunch. Taking into account for a trapper’s propensity to exaggerate, half that number would be a daunting experience. Weighing a thousand pounds or more, agile as a cat and able to run at speeds of 35 mph made them a formidable foe. They had a nasty disposition to boot. A grizz could be as much a threat as a whole band of hostile warriors. Other ways of shortening the life expectancy of a trapper included fatal quarrels with fellow trappers, thirst, weather, accident, disease and hunger.

The quest for food was an obsession in a land where one would suppose that game would always be plentiful. A hungry trapper, not knowing where his next meal was coming, might sit down and eat four or five pounds of meat at a sitting or, if he would get a chance to enjoy another meal before something unforeseen would cause him to go under.

Trappers preferred a steady diet of meat but there was also the danger of dysentery, which could be deadly

Trappers reported having to subsist on ants and crickets in the deserts or making stew with the ears of their mules. Others mentioned soaking their rank-smelling moccasins until they were soft enough to eat. So, when he did find a place where game was plentiful a feast was held and he ate until his “meatbag,” or stomach, was filled.

When it was available he used bison dung for fuel declaring it imparted a peppery flavor to the meat. Otherwise, he used dried aspen, which made a good fire without much smoke. Pitch pine was good too and was the most flammable.

Visitors must have been aghast watching the ritual of feasting for the trapper’s put on quite a show. If the meal was to be bison, the hump ribs would be placed over the coals to broil and while waiting for the main course to cook, they would break open a thighbone and dig out the marrow, also known as “trapper’s butter.” Then they scooped blood out of the cavity and added that to a little water, enough to make a soupy substance. Adding to the brew the bone marrow and sprinkling on some salt and pepper, the “mountain cocktail” was ready to drink. This no doubt satisfied some physiological need but it usually turned the stomach of any outsider visiting the camp.

Another delicacy the trappers enjoyed was the tail of the beaver which contained plenty of nourishing fat.

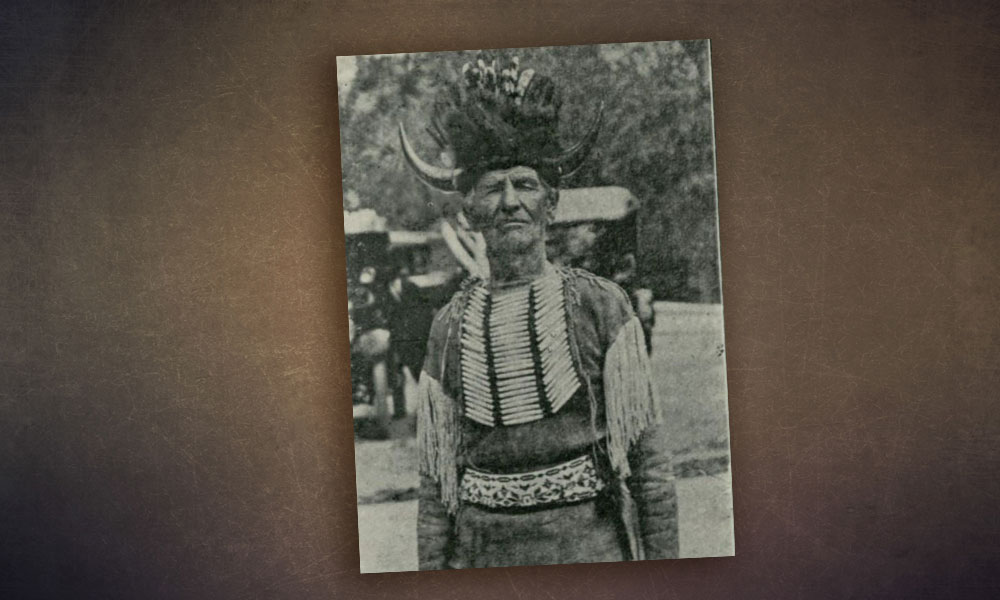

The trapper’s clothes were made of leather as it proved more durable and lasted longer than wool or cotton fabrics. Leather could also be made water-proof by applying generous amounts of animal fat. While eating he rubbed his greasy hands on his clothes. The fringe along the seams provided a nice stylish tough but it also caused the water to run off rather than soak in during wet weather.

Some designed a coat of mail by hardening the tough bison hide much like the leather armor worn by Spanish soldiers in Arizona and New Mexico who were called Soldados de Cuera or “Leather Jacket Soldiers. This increased his chances of survival in battle.

After the season the trapper would “hole-up” for the winter. A hole was a spot protected from the brutal winter winds and game was plentiful.

Spending a long winter alone in the mountains is something few could tolerate. The only solution in the North Country was to take a pretty young Indian girl for a bride. They were sold by their fathers for a horse, gun, powder and ball, jug of whiskey or maybe $2,000 in beaver skins for a chief’s daughter.

A wife was not only a good companion on a cold night but she could cook, sew, and help with the work.

Artist George Catlin wrote of the usual rate of exchange: “Their women are beautiful and modest……and if either Indian or white man wishes to marry the most beautiful girl in the tribe she is valued only equal perhaps to two horses, a gun with powder and ball for a year, five or six pounds of beads, or a couple of gallons of whiskey.

The Native American usually found marriage to a white trapper prestigious for it raised her esteem within her tribe. The mountain men loved to lavish their wives with gifts of jewelry, bangles, “foofaraw” cloth, ribbon, and equally important, modern utensils such as metal cooking utensils like cooking pots. In exchange she made his clothing, cooked gathered firewood. They also took great pleasure in making their husbands clothing “out shine” those of his fellow trappers.