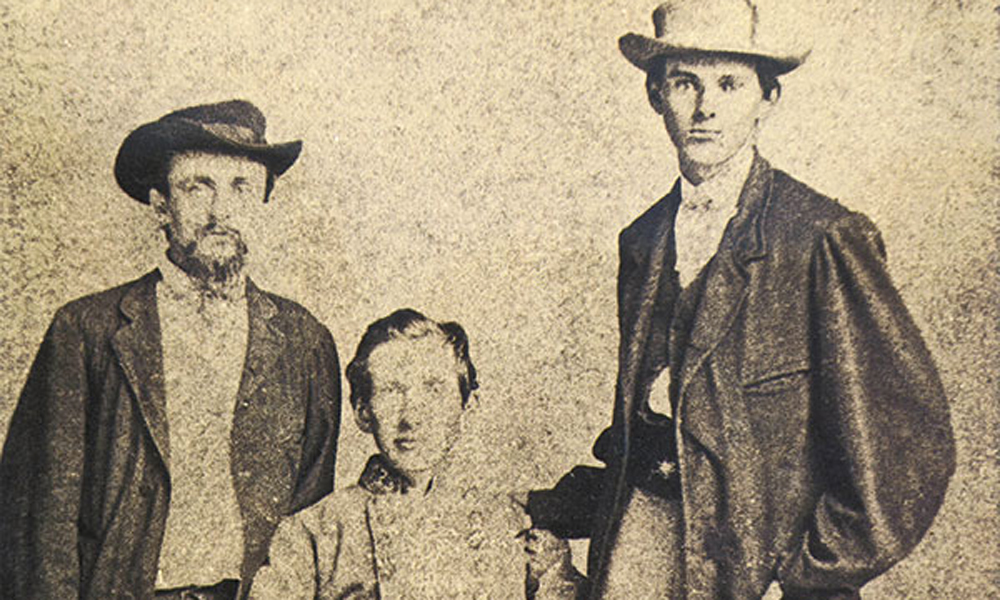

— All photos Wilbur Zink Collection courtesy Heritage Auctions, June 22-23, 2013, unless otherwise noted —

Nobody asks, “Who is Jesse James?”

Books, movies, newspapers, dime novels have all shared his story, from the days when the bank and train robbing outlaw was still walking the frontier to today when only his spirit remains. Yet the single book written about Jesse’s older brother Frank is a fake. The Only True History of the Life of Frank James was not “written by himself,” unless you believe the author of the 1926 book, Joe Vaughn, who claimed he was the real Frank James. Ramon Frederick Adams certainly didn’t approve, writing, “Much trash has been written about the James boys, but both Frank and Jesse would turn over in their graves if they knew about this one.”

The closest historians get to books about Frank is the 1898 tome focused on Frank’s murder trial, followed up by Gerard S. Petrone’s 1998 Judgment at Gallatin, and books focused on the two brothers, starting with the 1987 family history about Frank and Jesse written by Phillip Steele and leading up to Ted P. Yeatman’s Frank and Jesse James in 2003. But even Steele was more attracted to Jesse’s story, than Frank’s, following up his book with The Many Faces of Jesse James. Countless books have Jesse James in the title, with no reference at all to Frank.

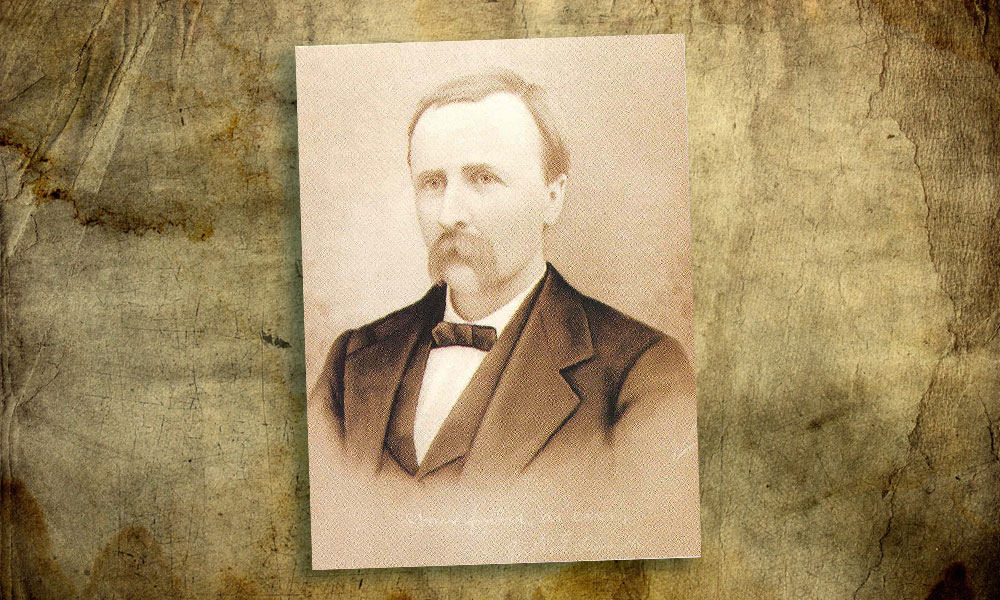

— Wilbur Zink Collection courtesy Roy Young —

Hollywood did release The Return of Frank James, with Henry Fonda back in his role of Frank for the 1940 sequel to the Jesse James film that hit movie theaters the year before. Both films were notorious for their historical inaccuracies. Twentieth Century-Fox may have purchased the rights to the James brothers’ lives, but the Frank James movie distortions included Frank playing a role in the deaths of the Ford brothers (he didn’t).

Yet Frank was the man who brought Jesse to the dance, so to speak. Even so, people flocked to Jesse, which was obvious even during his lifetime. One of Frank and Jesse’s sympathizers, John Newman Edwards, who rode out to the James family farm in Kearney, Missouri, to meet them, best captured the differences between the brothers, in his St. Louis Dispatch article, published on November 22, 1873:

“Jesse laughs at everything—Frank at nothing at all. Jesse is light-hearted, reckless, devil-may-care—Frank sober, sedate, a dangerous man always in ambush in the midst of society. Jesse knows there is a price upon his head and discusses the whys and wherefores of it—Frank knows it too, but it chafes him sorely and arouses all the tiger that is in his heart. Neither will be taken alive. Killed—that may be.”

Edwards was prescient about Jesse, who met his untimely death when one of his own gang members, Robert Ford, turned on him, shooting the 34 year old in the back of his head, while he cleaned the dust off a picture hanging on his living room wall. But Frank was “taken alive.” Later that year, on October 4, 1882, he surrendered to Missouri Gov. Thomas Crittenden. Thus began four years of legal wrangling over the outlaw’s fate.

Who was the real Frank James? Let’s find out.

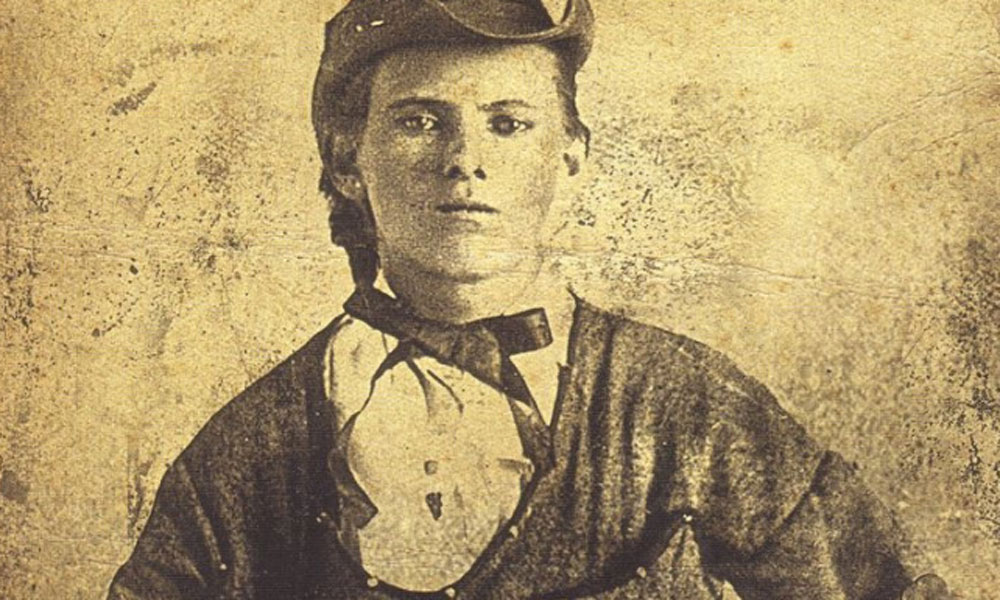

— Photo courtesy Jesse James Birthplace in Kearney, Missouri —

Fuel for Criminals

The year of Frank’s birth, 1843, marked a turning point for his impoverished parents, Robert and Zerelda James. The first large wagon train to Oregon departed that spring, and Robert took advantage of a necessary tool for these journeys—rope—by farming hemp as his crop. After Alexander Franklin James was born on January 10, 1843, he and his parents moved into a three-room cabin by a creek in Clay County, which would be the James family home for the rest of their lives.

Frank’s brother, Jesse, was born on September 5, 1847, followed by Susan Lavenia, on November 25, 1849. The next year, their father died of cholera while prospecting for gold and preaching to miners in California. Zerelda remarried twice, first to Benjamin Simms in 1852 and then to Dr. Reuben Samuel in 1855. With Samuel, she would give her brood four step siblings: Sarah Louisa, John Thomas, Fannie Quantrell and Archie Peyton.

Frank, who was seven or eight when his father died, clung to his papa through the words he loved, reading his father’s sizable library, especially the works of William Shakespeare. Frank’s propensity for quoting Shakespeare would come up in his trial in 1883, when the Rev. Jamin Machette testified that the day before an 1881 train robbery in Winston, a man named Willard (alias for Frank) and a man named Scott (alias for Jesse) ate a meal at Machette’s home, and that the man named Willard had recited long passages from Shakespeare’s works.

The James family were slaveholders, so when abolitionists spilled blood from Kansas into Missouri, Frank joined the Confederate cause, helping to defeat Union forces at the Battle of Wilson Creek in August 1861. Six months later, Frank was captured. He lied through his teeth that he would not take up arms against the Union, then returned home and joined William Clarke Quantrill’s guerrillas. This gang of men is where Frank met bushwhacker Cole Younger.

— True West Archives —

In January 1866, Cole rode over to Kearney to visit Frank and, for the first time, met Frank’s brother, Jesse, recalled Homer Croy, an author and screenwriter who grew up near the James family farm. “He’s kind of poorly,” Frank described Jesse to his comrade. “He picked up a couple of lung shots April 23, 1865, when he was coming into the Burns schoolhouse to surrender.”

Jesse joined “Bloody Bill” Anderson’s nexus of Quantrill men around 1863 or 1864. Frank would place Jesse with him at a battle near Centralia, boasting to the St. Louis Republic in 1900, “The only battles in the world’s history to surpass Centralia are Thermopylae and the Alamo.” He credited Jesse for killing the commander, 39th Missouri Infantry Maj. A.V.E. Johnson. After Jesse recovered from a severe chest wound he got while fighting in 1865, Jesse and Frank moved back to their Missouri farm.

That momentous meeting in 1866, though, is where Cole and Frank first hatched the plot to rob a bank, in the name of the Confederate cause, Croy reported, writing, “The idea was breathtaking. Everybody hated banks. They charged usury; they cheated farmers.”

This was a time, remember, when the Federal Deposit did not yet insure bank funds; money stolen was lost forever.

The day before Valentine’s Day, in February 1866, Cole, Frank and 10 other ex-guerrillas showed one bank in Liberty little love, reportedly stealing roughly $57,000, equal to about $890,000 today. “After things cooled down, Frank James came home and told Jesse about it. It made Jesse’s tongue hang out,” Croy wrote.

That first daylight bank robbery in post-Civil War America would fuel robbery after robbery for the James brothers until one disastrous raid, on September 7, 1876, in Northfield, Minnesota. Two weeks later, following a gunfight near Madelia, gang member Charlie Pitts died. The Younger brothers—Cole, Bob and Jim—were caught and sent to prison. The James boys had already split off from the gang.

Cole would outlive Frank by one year; he had already outlived his brothers, Bob, who died in prison of tuberculosis in 1889, and Jim, who committed suicide in 1902. But Cole never implicated the James brothers in the Northfield disaster.

The year before Northfield, the James family had suffered a tragedy. The Chicago-based Pinkerton Detective Agency, hired by railroad companies, had been pursuing Frank and Jesse’s gang since 1874. On January 26, 1875, a gang of Pinkerton men surrounded the James family farm and threw flaming pots inside the house, to flush out the brothers, mistakenly believing them to be home. A flare exploded and killed eight-year-old half-brother Archie and blew off mother Zerelda’s right arm.

Allan Pinkerton admitted the agency’s involvement in the raid on “Castle James,” as the detectives called the James family farm, writing, “I hear that the Jameses and Youngers are desperate men and that when we meet it must be the death of one or both of us…. There is no use talking, they must die.”

Before the attack, Allan gave his men these instructions, “Above everything, destroy the house to the fringe of the ground…. Let the men take no risk, burn the house down.”

If Frank and Jesse had been home and killed in that attack, the Pinkertons probably would have been heralded for ridding America of these criminal robbers. But killing a child and wounding a mother earned sympathy for the James family.

At the same time, when nearly six years later, Jesse was killed, a collective sigh was heard across the nation. A year after Jesse’s murder, one man wrote to his brother back East, “I think the days of lawlessness & train robbing in Missouri are about over….”

The assassination of Jesse James by the coward Robert Ford, as one critically-acclaimed book-turned-movie is titled, had severed a criminal bond between brothers.

Seeking Peace

Frank officially ended his outlaw career with a dash of chivalry, presenting his gun belt to the governor with these words, “I want to hand over to you that which no living man except myself has been permitted to touch since 1861, and to say that I am your prisoner.”

Why would Frank take such a risk to turn himself in to face his outstanding warrants in Missouri and Alabama?

Frank was no longer a solitary man. He was no longer the young man from 17 to 21, willing to “do desperate work or to lead a forlorn hope,” one of those boys who “will go anywhere in the world you will lead them,” as he told the St. Louis Republic on August 5, 1900. “As men grow older they grow more cautious, but at that age, they are regular daredevils.”

Frank was a family man. He had married Annie Ralston in Omaha, Nebraska, on June 6, 1874, just six weeks after Jesse married his first cousin, Zerelda or Zee. Annie gave birth to their only child, a son, Robert Franklin James, on February 6, 1878. When Jesse was killed in 1882, Frank must have looked at three-year-old Robert and said, “I have to get out of this life.”

— Zerelda with tourists photo Courtesy Heritage Auctions, June 13, 2008 —

The letters that Frank wrote during his prison stay as he awaited his trials convey the deep love he felt for his wife and child, and they for him. On Valentine’s Day in 1884, while he sat in a jail in Huntsville, Alabama, having been acquitted of the Missouri charges, but still waiting for his trial over the Muscle Shoals payroll robbery in 1881, Frank concluded his letter to Annie with, “Kiss Rob and remember me to Ma and all the family. Hoping to hear from you soon. will say good night.”

When Frank was still in Missouri, in Gallatin, awaiting his trial, on March 24, 1883, he sent a drawing of a bird to his son Robert, printing on the reverse, “God Bless My Little Man From Papa.”

When Frank sent Annie a pen and ink sketch he made of him kissing her through the jail bars, his dear wife he so desperately missed and wished to hold once more, she added a Maggie May Danehy poem to his drawing and wrote, on the reverse side, “Still my griefs are mine.”

Annie was the one who had corresponded with Missouri Gov. Crittenden to feel him out over her husband Frank surrendering to him. Crittenden’s response on June 2, 1882, by way of his secretary F.C. Carr, stated that the governor “can take no action upon your bare suggestion,” yet “desires to see you in person, and hear you freely, as to your proposals etc.”

Frank surrendered on October 4, 1882, and four years later, he walked out a free man. “The issue of Frank James being allowed to go free after so public a life of crime is still hotly contested today,” Marley Brant wrote in The Outlaw Youngers.

She added, “Edwards used every personal political connection, favor, and influence at his disposal to see that Frank James went free. Those who were selected to represent Frank, most of them without fee, later went on to become members of congress and to hold various judicial offices. A Democratic jury was permitted, and people such as Gen. JO Shelby and the maimed Zerelda James Samuel were allowed to witness, characterizing Frank as a Southern hero and Jesse James as one who was methodically hunted down and murdered by the state of Missouri for little cause other than the fact that he was a former Confederate. The surrender and terms of trial were so well planned that there was never really any doubt as to their favorable (to Frank) outcome.”

When John S. Marmaduke took on the role of governor in Missouri in 1885, Edwards convinced him not to extradite Frank to Minnesota for any charges that dealt with crimes committed in that state. Minnesota, of course, was home to the Northfield raid, where citizens armed themselves and courageously fought back, yet lost two of their men in the bloodshed.

Frank left behind his life of crime and found work in various jobs, as a shoe salesman, a Burlesque ticket taker (the theatre promoted, “Come get your ticket punched by the legendary Frank James”), an AT&T telegraph operator, the betting commissioner for a horse racetrack and a berry picker at a Washington ranch. He even joined up with his old comrade, Cole Younger, on a Wild West show tour through the South, and gave lectures on how crime does not pay.

Frank lived in Nashville, Tennessee, in various places in Missouri (including St. Louis during the 1890s) and in Oklahoma from 1907 to 1912, says Roy B. Young, the first vice president of the Wild West History Association. In his groundbreaking article about Frank James’s Oklahoma years, published in the March 2017 issue of the WWHA Journal, Young revealed why Frank moved with Annie to Oklahoma, where their son Robert lived, from his home state of Missouri, sharing a speech Frank gave at the August 1904 reunion of Quantrill’s men in Independence, Missouri.

“I have been in Ohio, Pennsylvania and other states we learned to hate because they gave birth to the federal troops we hated so well, and their people have treated me like a man,” Frank told the war-scarred veterans. “But here in Missouri, among my own people, I am unhonored and unsung, then why should I not turn to the belief of the people who have, in my declining years, proved my friends?”

His mother’s death brought Frank back to the James family farm in Kearney, where his story had begun all those years ago. After his mother died on February 10, 1911, on her way home from visiting him in Oklahoma, Frank planned to summer in Missouri and winter in Oklahoma, which he did, until 1913, whereafter he stayed in Missouri permanently.

At the James family farm, Frank gave 25-cent tours and sold souvenir pebbles to folks who stopped by to visit the grave of Jesse James and his childhood home. A man perpetually outshone by his younger brother in the annals of history, Frank left behind his wife, Annie, and their son, Robert, dying from a stroke, at the age of 72, on February 18, 1915.

The Outlaw Glorified

Frank had long ago shed the outlaw persona that froze his brother in the limelight. Would Jesse have done the same, if Frank had been killed all those years ago, instead of him?

Perhaps we all grow up into those crotchety old men yelling, “Get off my front lawn,” and into those wretched old women who over worry about imagined terrors. In 1902, a nearly 60-year-old Frank sought a court order to prevent the play, The James Boys in Missouri, from being shown on stage in Kansas City, Missouri. He voiced his concern:

“The dad-binged play glorifies these outlaws and makes heroes of them…. I am told the Gilliss Theatre was packed to the doors last night, and that most of those there were boys and men. What will be the effect on these young men to see the acts of a train robber and outlaw glorified?”

Meghan Saar is the editor of True West Magazine. She wishes to thank Roy B. Young, Eric James and Mark Lee Gardner for their research assistance. Wilbur Zink passed on to the great beyond before he could finish his Frank James book, but you can learn more about the researcher in the magazine’s profile of him, published on TWMag.com, “Collecting American Outlaws.”