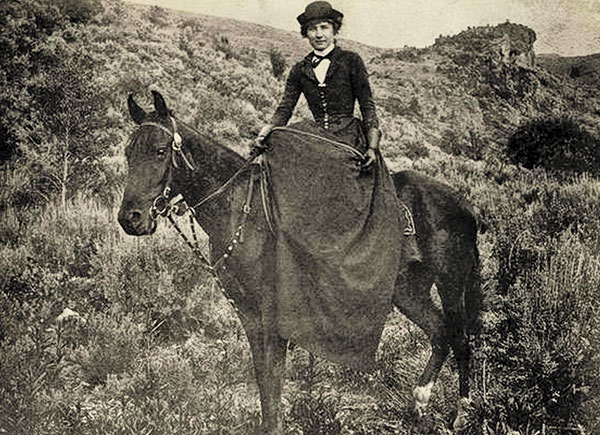

— All images True West Archives unless otherwise noted —

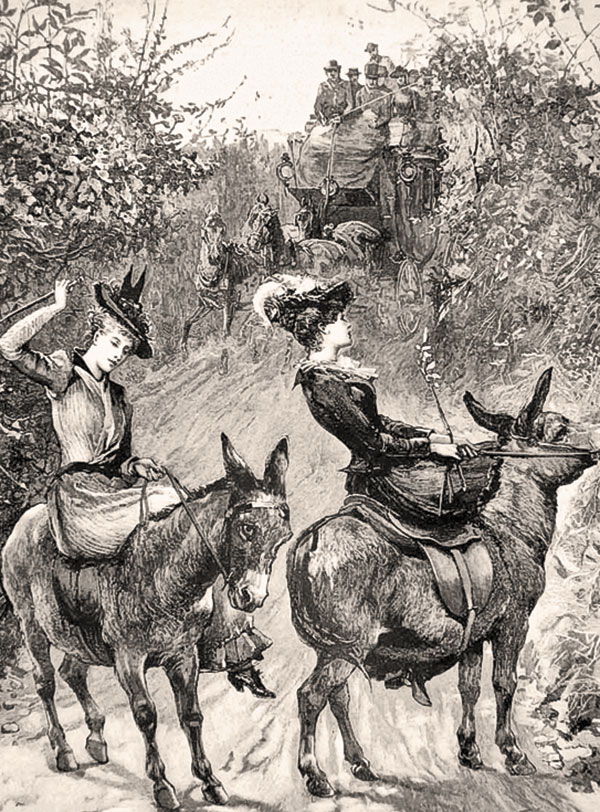

As absurd as this may sound, the sidesaddle took hold in the 14th century to protect the virginity of a teenaged princess traveling across Europe to wed the young King of England.

Surprised? Don’t feel alone. Most assume the sidesaddle was the natural outcome of fashion, demanded by the long, flowing, sometimes over-hooped skirts favored for so many centuries.

But no, protecting the royal hymen was the reason.

For some 500 years, women were told the only way a “proper lady” sat on a horse was sideways, holding on for dear life, a passenger on a 1,500-pound animal she could barely control.

The fate of that princess makes the story even more ludicrous.

Virtuous Virgins

Princess Anne of Bohemia, a predecessor of the modern Czech Republic, was the daughter of the most powerful monarch in Europe in 1382 when she left for England to wed King Richard II. To ensure her virgin marriage, ruling men instructed her to ride aside, rather than astride.

“Good Queen Anne,” as she’d eventually be called, arrived sitting in a large padded chair, holding onto a pommel in front, both feet resting on a wooden plank that hung on the left side of the animal. (Both men and women mount a horse from the left.) Someone led her horse.

She wed a tall, handsome boy she came to love, but who history remembers mainly through William Shakespeare, the playwright who blamed “Richard II” for the Wars of the Roses.

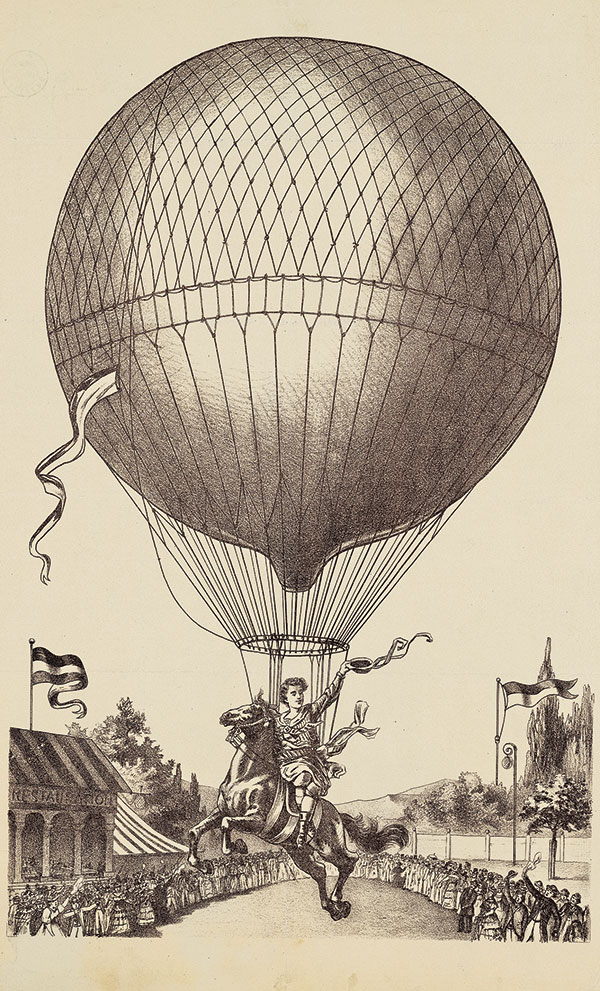

— Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection —

Women hadn’t always ridden so askew.

Although ancient Greek sculptures depict women riding aside, it was an option, not a demand. Joan of Arc didn’t ride into battle in the 1400s as a dainty maid. Geoffrey Chaucer depicted his “Wife of Bath” riding astride in the 1300s. Central Asian women mounted horses like their brothers did, and Amazon women were famous for both their trousers and riding astride.

But then came Anne and the fixation on “virtuous virgins.” Folks like to mimic royals, so the idea of a sidesaddle spread.

By 1600, riding aside was the only way a “decent” woman could ride a horse without scorn. Most women went willingly along—except for Catherine the Great, of course, who was so powerful, she decreed her court would all ride astride.

“The reins, both of personal power and individual equestrian control, had been taken away by men who now restricted a woman’s political and equestrian destinies,” CuChullaine O’Reilly wrote for the Long Riders Guild Academic Foundation.

Sidesaddle Designs

The earliest sidesaddle design was little more than a pillow and a piece of wood that faced the woman off to the scenery on the left side of the horse. This replaced the pillion—a small padded seat where the woman rode behind a male rider. The newer saddle allowed the lady to ride alone, but still gave her no control over the animal—she sat so precariously, it’s a wonder all rides didn’t end in injury. Another rider held the reins and led her horse along; she could do little but cling to the pommel and hope she didn’t fall off. The woman was not exactly “riding” the horse; she was just sitting on it as it moved.

In the 16th century, Catherine de’ Medici is credited with inspiring a saddle that allowed the woman to face forward. In this saddle, she hooked her right leg around a pommel on the saddle and placed her left foot in a stirrup. This gave her a fighting chance to stay in the saddle and handle the reins herself. But even this saddle only allowed her to proceed slowly—any speed was dangerous.

The sidesaddle we still know today was invented in the 1830s by Jules Pellier. It had a fixed pommel to support the rider’s right thigh and a revolutionary second pommel for the left leg. This allowed more security and control, giving the woman the freedom to stay on top at a gallop and to jump fences.

By now, the sidesaddle was a permanent fixture for women and any suggestion to the contrary was met with harsh words. Like the Los Angeles Times male columnist in 1905: “The woman does not live who can throw her leg over the back of a horse without profaning the grace of femininity; or grasp with her separated knees the shoulders of her mount without violating the laws of good taste; or appear in the cross-saddle with any semblance of dignity, elegance or poise.”

Even some female writers agreed. As the 20th century dawned and balked, British author Alice Hayes saw the first rumblings against a sidesaddle, denouncing these “feminine desperadoes.” Although she vehemently argued women should ride sidesaddle, she did admit that the sidesaddle’s impractical design placed women in harm’s way.

“The fact of a lady having to ride in a side saddle, subjects her to three disadvantages: she is unable, without assistance, to mount as readily as a man; she cannot apply the pressure of the leg to the right side of the horse; and she cannot ‘drop her hands’ in order to pull her horse together to the same extent as he can,” wrote Hayes, in her 1893 book, The Horsewoman: A Practical Guide to Side-Saddle Riding.

By 1900, American women were split on the issue—along geographic lines. Women in the East clung to the sidesaddle as proper and necessary, while Western women saw them as impractical and dangerous. Western women were far more likely to use a horse for farm and ranch labor than their Eastern sisters, who saw the horse as a weekend entertainment.

“Not one of us would tolerate the old-fashioned sidesaddle,” said one of the record 25 women inducted into the Vaquero Riding Club, composed of expert horsemen of Spanish heritage, during the early 1900s.

Her proud statement to the Los Angeles Times was just the beginning.

Meet “Two-Gun” Nan Aspinwall

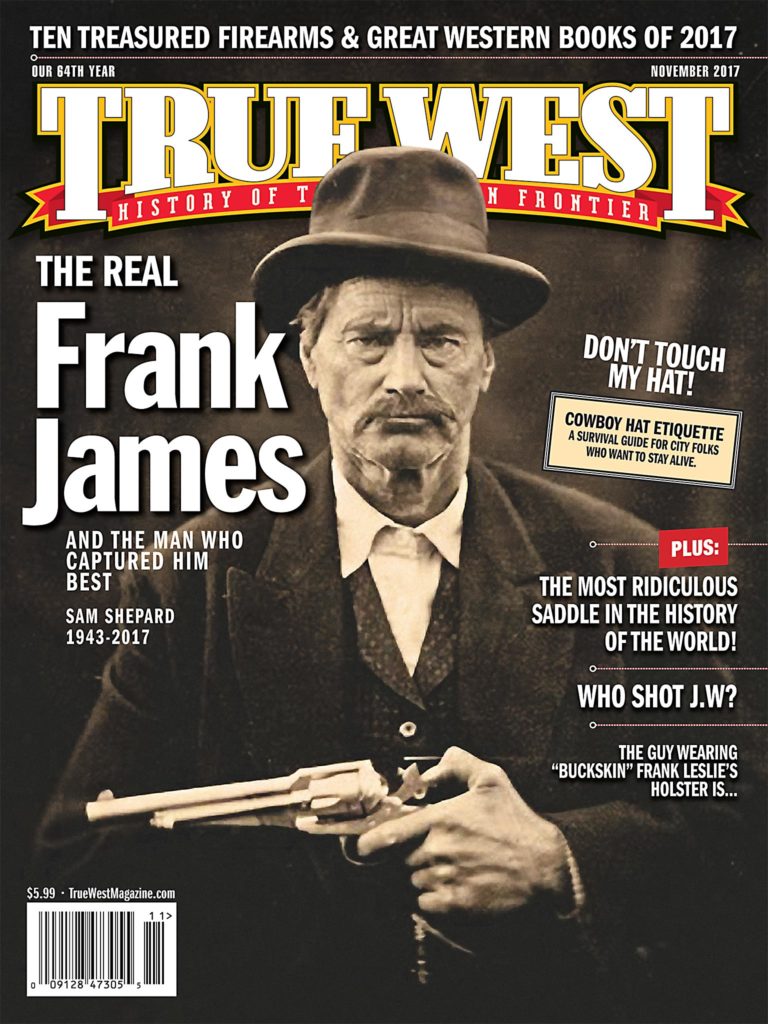

“Two-Gun” Nan Aspinwall began calling herself “Montana Girl” in 1906, two years before she started performing with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Great Far East troupe, where she became a hit.

Did the Two Bills challenge her to ride solo across the nation in 1909, to promote the troupe? No woman had ever undertaken such a ride—and of course, she wouldn’t ride aside. She also wouldn’t be wearing a flowing skirt, but a split skirt that some still considered scandalous.

In September 1910, “Two-Gun” Nan accepted the challenge and took off from San Francisco to New York City on a mare named Lady Ellen. She carried a letter to New York City Mayor William Jay Gaynor from San Francisco Mayor Patrick Henry McCarthy.

Her horse went through 14 pairs of horseshoes. Nan insisted on doing all the shodding herself, just as she took care of anything else her horse required.

In all, “Two-Gun” Nan and Lady Ellen traveled 4,496 miles in 180 days, arriving in New York City on July 9, 1911. One New York newspaper announced her arrival with a picture and the headline, “Snappy Western Girl Who Rode Horse Clear Across Continent.”

Another reported, “A travel-stained woman attired in a red shirt and divided skirt and seated on a bay horse drew a crowd to City Hall yesterday afternoon.”

Her historic ride was retold on radio and television during the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s, and she served as a technical adviser when her ride was showcased on an episode of Death Valley Days.

“Two-Gun” Nan died in 1964 at the age of 84, living out her last years quietly in California.

Sisters in the Saddle

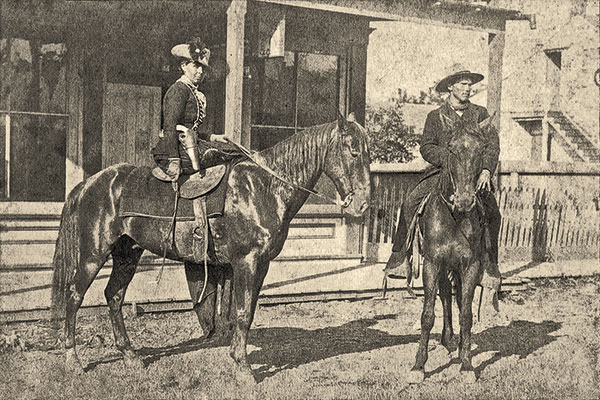

In 1912, Alberta Claire made her 8,000-mile solo trip from Wyoming to Oregon, down through California, across the Arizona desert and into New York City. Along the way, she declared to anyone who’d listen that she had both the right to ride astride and the right to vote.

History does not record whether or not Claire ever met New York’s Inez Milholland, though they were contemporaries. Nevertheless, these two women were sisters in the saddle.

Nobody tied politics and riding astride as did Milholland, the beautiful face of the suffrage movement.

Milholland was born into a liberal family of means in Brooklyn in 1886. She became a lawyer—turned down by Yale and Harvard because of her sex—and gave lectures throughout the nation to support women’s rights. She led suffrage marches in 1911, 1912 and 1913, while astride a white horse named Gray Dawn.

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

While all dressed in white, Milholland appeared in her most memorable suffrage march, on March 3, 1913, on the eve of President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Riding Gray Dawn, the 26 year old was leading the Women Suffrage Procession of 9,000 marchers in Washington, D.C. when thugs attacked. “Women were jeered, tripped, grabbed, shoved and many heard ‘indecent epithets’ and ‘barnyard conversation,’” the Library of Congress reports.

Milholland drove off the attackers, at least temporarily, but as police stood by—some of them jeering themselves—more than 300 women were hurt and required medical attention. Deaf and blind Helen Keller was so unnerved by the attacks that she couldn’t give her speech.

Seeing these women being blooded and broken during a peaceful march turned the public’s stomach. History records this as a turning point for the women’s right to vote. Milholland emerged as a heroine of the movement.

While on a speaking tour of the west in Los Angeles, she collapsed and died of pernicious anemia in 1916.

From Sidesaddle Skirt to Pants

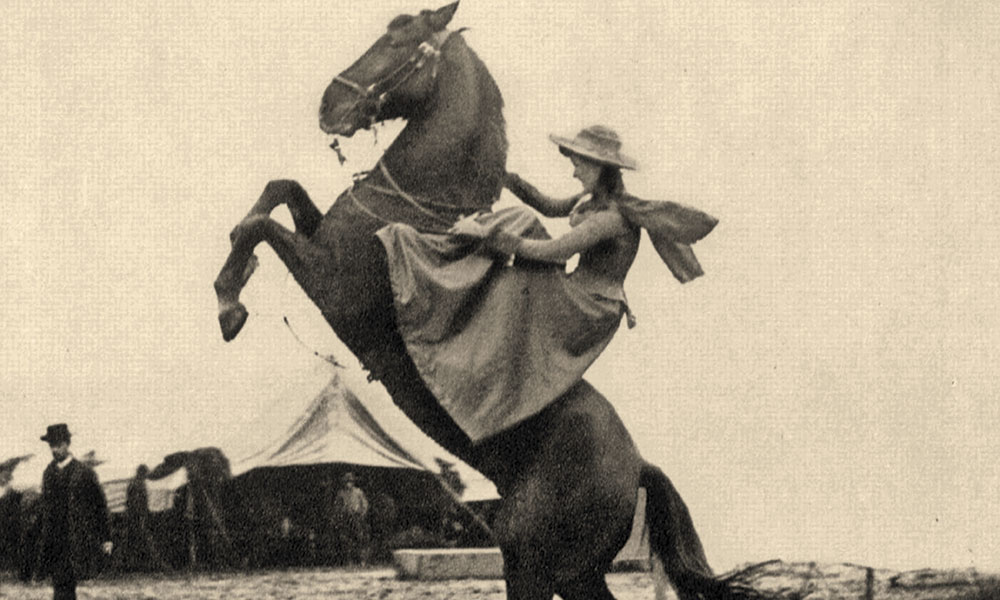

Western women were also making their mark as North America’s first professional female athletes—in rodeos. Not one of them considered riding sidesaddle as they put their lives on the line to entertain while on horseback.

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

Strangely enough, though, one of the greatest rodeo queens got her start riding sidesaddle. In her first rodeo event, at a county fair in 1906, 13-year-old Vera McGinnis was the only rider who rode sidesaddle, in a dress, competing against much older girls. “It so happened that the horse show judge was a bit old fashioned and frowned upon such things as girls riding clothespin-style so Vera won first prize, a gold-handled umbrella,” True West reported in 1991.

McGinnis went on to become famous for putting pants on women in the ring and for her daring stunts, which included circling a horse’s belly at full gallop.

Fall of the Sidesaddle

When the end came, it came quickly. Less than a generation passed before the sidesaddle became a quaint anachronism, noted O’Reilly, in her article, “Sidesaddles and Suffragettes, the Fight to Ride and Vote.”

“The fall of the sidesaddle is linked to the rise of female liberty, for it was the dawning of political freedom which brought about the overdue death of this repressive equine invention,” she wrote.

Once women were offered the option, she noted, “they abandoned the sidesaddle in droves in favor of riding astride.”

Nobody blinked when that beautiful child, Elizabeth Taylor, rode astride in 1944’s National Velvet—a girl not hankering to be a helpless passenger on a horse, but racing in the Grand National steeplechase.

Just look in The Book of the Horse—a nearly 900-page masterpiece by Brian Vesey-Fitzgerald—and note he didn’t cite a single reference to the sidesaddle. He didn’t recognize the political straightjacket the sidesaddle had been for centuries to women, but modern writers make the connection clear.

What became of dear Anne of Bohemia, our sidesaddle star, whose royal virginity would impact millions of women over 500 years?

She died after 12 years of marriage. Childless.

Jana Bommersbach has earned recognition as Arizona’s Journalist of the Year and won an Emmy and two Lifetime Achievement Awards. She cowrote the Emmy-winning Outrageous Arizona and has written two true crime books, a children’s book and the historical novel Cattle Kate.