The American West has intrigued international audiences since the first European explorers brought back stories, treasures, artifacts and, most important, Native peoples to the 15th- and 16th-century royal courts of Europe. Flash-forward nearly 400 years and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show with his Sioux performrs arrives in Paris with flourish and fanfare, and a captivating love affair between the French people and the American West begins.

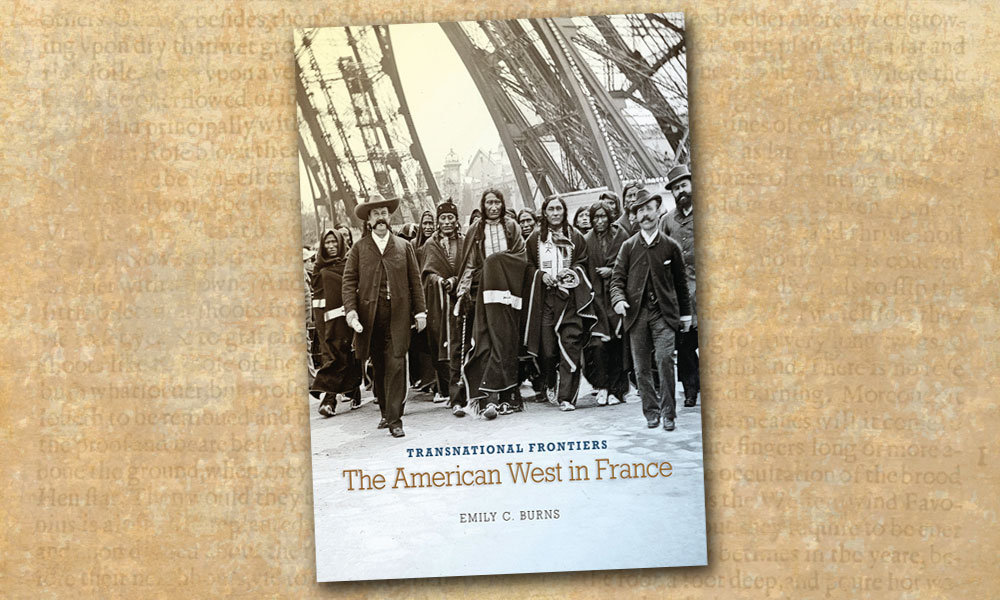

Author Emily C. Burns’ Transnational Frontiers: The American West in France (University of Oklahoma Press, $45) captures the complex relationship between France, the United States and its Indian nations. “Though the United States and France are two central national actors in this international exchange,” Burns says, “this project also treats the Lakota nation as an active participant within constructions of the American West in France.” She adds, “[T]he idea of a multinational American West functions as a lens through which to interpret the political and cultural relationships between the United States, France, and the indigenous communities in their uses of the American West.”

The ethnographic, cultural and historical journey that Burns’ Transnational Frontiers takes from France, Europe and back to the United States will inspire readers to reformulate their understanding of the three-way, international cultural exchange between the United States, France and American indigenous people between the Civil War and World War I. At the heart of Burns’ chronicle is the influence Native peoples—especially the Sioux, who traveled regularly with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West—had on the French intellectual interpretation of American cowboy and Indian culture. She eloquently concludes: “The tripartite international dialogue around ideas of the American West among the United States, France, and American Indian communities did not halt with World War I, but the terms of contact shifted dramatically.

Beyond its beautiful design and ample illustrations, Transnational Frontiers is an invaluable resource for further research on what the author describes as the “French exchange.” Burns’ endnotes and selected bibliography provide significant insight into her interpretation of the primary and secondary sources she used. They trace the Auburn University assistant professor of art history’s path to her conclusions about France’s cultural captivation with the West, and serve as a primer to the researcher interested in pursuing further answers to her list of thoughtful questions about the influence of the French on American culture. These questions include: “What role did French artists who traveled to the United States have in building up mythologies of the American West for audiences on both sides of the Atlantic? What is the relationship between impressionism and representations of the American West? How did American Indian performers touring France with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and other traveling spectacles carry narratives from this experience back to their communities?” I, for one, am eager for Burns to answer these and many other questions in her follow-up to this and enlightening volume.

—Stuart Rosebrook

https://truewestmagazine.com/building-western-library-preston-lewis/