— All photos Courtesy Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas unless otherwise stated —

With cold, unblinking eyes, a well-dressed gentleman stared at J.W. Jarrott as he walked with his wife, Mollie, down the main street of Lubbock, Texas, in August 1902. J.W. said to Mollie: “There’s a man I’d rather not see in this country.”

After the Jarrotts passed, the stranger quietly disappeared.

Settling a Slice of No-Man’s Land

That spring, J.W. had begun settling his family and 24 “nesters” on uninhabited plains southwest of Lubbock—a semiarid, windswept wilderness, without trees or flowing streams.

Before the Santa Fe railroad reached Lubbock in 1909, only 293 hardy pioneers populated the county, the 1900 census reported. Just 44 lived to the west, in Hockley County.

J.W. brought his homesteaders to southern Hockley County; the northern part was largely owned by XIT Ranch. A broke Texas had traded this land after the capitol burned down in Austin. In 1882, the legislature granted a Chicago group 3.05 million acres in exchange for a red granite capitol, a frontier skyscraper that stands to this day.

Cattle barons resented any intrusion on “their” turf—particularly by nesters. And particularly J.W.

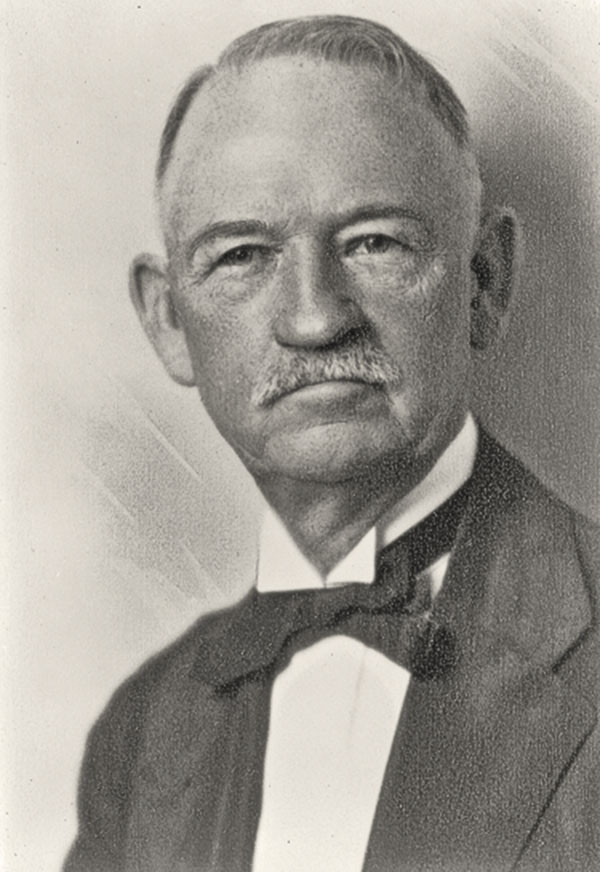

The lawyer had seized an opportunity to settle a slice of no-man’s land, pointed out to him by his friend, the commissioner of the Texas General Land Office, Charles Rogan. A surveyor error left an unfenced vacancy that ranchers utilized as free grasslands. Rogan classified this strip “school land” and placed it on the market to homesteaders, pursuant to Texas’s Four-Sections Act.

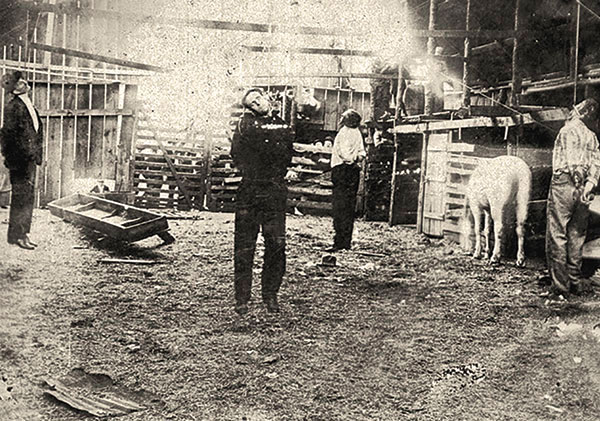

— Courtesy Cushing Memorial Library and Archives, Texas A&M University —

While Rogan waited for the legislature to pay his surveyor’s $3,000 fee, J.W. put up a “good faith” deposit of $500 to kick-start the survey. When Rogan refunded J.W.’s deposit, he gave him a copy of the survey. On April 24, 1902, J.W. filed the first batch of applications at the land office. In May, Mollie packed up the three children and left Stephenville to join J.W. on their four sections, totaling 2,560 acres.

Cattlemen were furious. They had spent large sums drilling, equipping and maintaining windmills every four miles across their ranges. Water was for cattle, not settlers.

“We realized that our settling meant an intrusion upon the cowmen’s grazing range,” Mary wrote, “but we had staked our lives here in the midst of their domain without even a fence to mark our own ground, and had no choice but to trespass as we gathered dry cow chips for wood and watered the horses and carried our water from their wells.”

Cattle Barons vs. Nesters

What was a mere 2,560 acres compared to the hundreds of thousands of grassland acres controlled by these cattle kings?

The cattlemen’s long-range fiscal future hinged on obtaining long-term leases on large blocks of land from the state for pennies per acre and then renewing those leases. They did not need squatters fencing off small tracts in their pastures or running up lease fees.

If the 1897 enactment of the Four-Sections Act was a gut punch to the cattle kings, they were in for another.

Whenever a lease terminated on school land, settlers could purchase four-section tracts within that acreage. Otherwise, cattlemen could renew the lease. Ranchers found a loophole. Prior to termination, they failed to pay the bill. When the lease lapsed, the only one who knew the land was available got it—the rancher.

In 1902, the Texas Supreme Court declared the “lapsed-lease” trick an unlawful deprivation of a settler’s opportunity to purchase land within a cattleman’s lease.

That summer, the cattlemen concocted another strategy to eliminate these squatters. They filed lawsuits.

The cowboy plaintiffs contended the land office should not approve the applications because the defendants were not “actual settlers,” but “bonus seekers” who sought to flip the land to others for a profit. J.W. contended they were “actual settlers,” unlike the cowboy plaintiffs, who were puppets of the Lake Tomb Ranch.

— Brownfield inset Courtesy Terry County Historical Commission; texas panhandle cattle photo courtesy USGS —

Death Waits on the Llano Estacado

By August 23, J.W. had secured applications for all his clients. On September 16, he’d have to defend those titles.

With Mollie sick in bed at the Nicolette Hotel in Lubbock, he left the children with her and headed to the homestead.

Outside present-day Ropesville, on August 27, J.W. stopped to water his horses at two windmills, the “Twin Towers.”

Hidden behind a dirt dam, an assassin fired his first round. Wounded, but not fatally, J.W. either jumped off his buggy or was thrown by the horses. The assassin kept firing. The last two struck J.W.’s back as he floundered in the water, desperately attempting to escape. The killer left the unarmed 41 year old in a trail of blood.

When his employer did not return, Jim Doyle rode to Lubbock, taking the northern route, not the southern path by Twin Towers. He reached Mollie by Friday and told her J.W. was missing.

“They’ve killed him!” she said.

On August 30, Doyle and others found J.W.’s body. His wagon was nearby, and somebody had hobbled both horses and hung the harness on the windmill tower.

Like wildfire, news of J.W.’s death swept across the South Plains. Fear invaded every homesteader tent and dugout—particularly among J.W.’s strip settlers. Would they be next on the hit list?

Yet Mollie refused to retreat.

The settlers bonded on mutual support. Mary Blankenship wrote, “The name Jim Jarrott became a legend among us, and his martyrdom served to spur us on. We determined not to pull up stakes and retreat back to the East.”

In 1903, Lake Tomb cowboy Ben Glaser admitted to a grand jury that he rode to Twin Towers, hobbled the horses and hung the harness, but he denied seeing J.W.’s body.

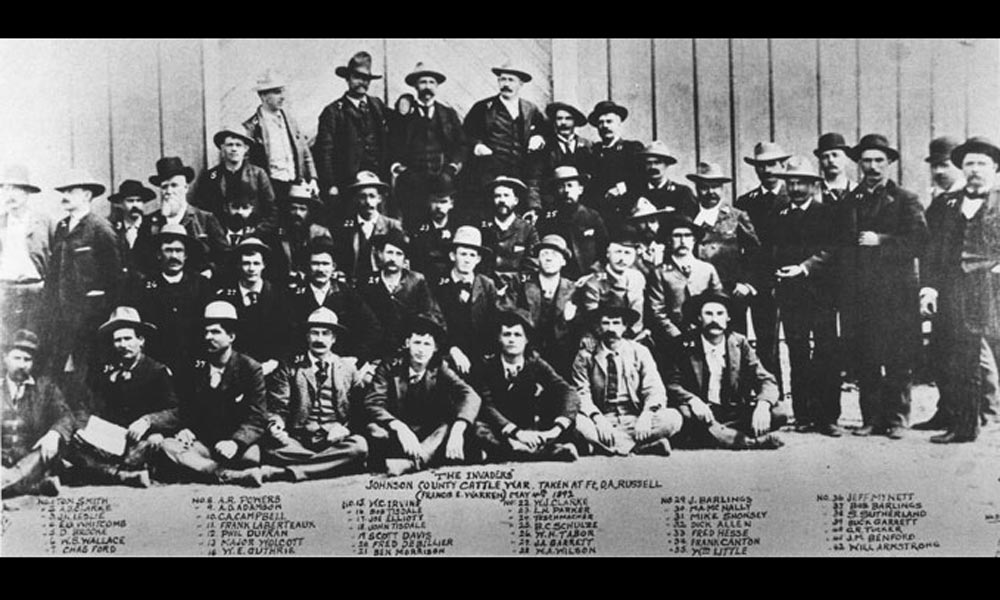

The grand jury returned murder indictments against Lake Tomb cowboys Glaser, Morgan Bellow, B.F. Nix and William Barrington, the latter indicted as the triggerman. He had also filed suit in 1902 to strip a J.W. settler of his homestead.

In 1905, the prosecution dismissed indictments for lack of evidence. The murder became a cold case.

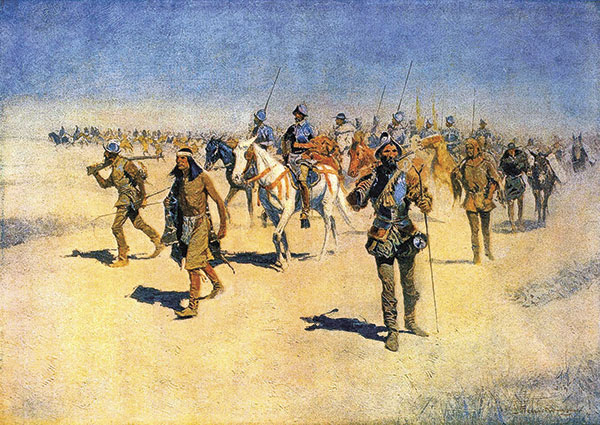

— Remington True West Archives; Marcy courtesy Library of Congress —

A Bizarre Deed-Shuffle

After killing J.W. on August 27, 1902, the assassin headed south on his horse, witnessed by 16-year-old Grace Cowan, the daughter of one of J.W.’s strip settlers.

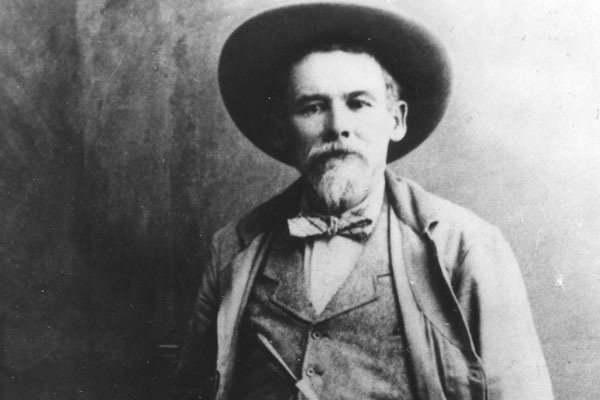

The only logical destination in that direction within riding distance was a ranch 12 miles south of the Cowan homestead. The cattleman who owned it was Marion Virgil “Pap” Brownfield, who also paid the accused triggerman’s bond.

Pap had owned ranches near Fort Worth and Abilene before leasing 52 sections in Terry County in 1894. In February 1903, his lease was expiring on four school sections.

Through tricks and fistfights, Pap secured title. That wasn’t enough of a victory. Pap also wanted four adjacent sections.

On January 23, 1903, nearly a year after D.J. Howard had purchased the land from Z.T. Joiner, a man who witnessed the first land swap paid Howard a $3,900 promissory note for the land.

Intoxicated by the prospect of grabbing a whopping sum for land he bought for $896, Howard found out only too late that the note was bogus.

A bizarre deed-shuffle began on January 30, when the man sold the land to Fort Worth banker W.H. Fisher for $4,100 cash. On March 7, Fisher conveyed the deed to Pap’s son Dick.

Why did the banker buy this land? Fisher was fronting Pap to pay the man’s assassination fee.

So, who shot J.W.?

— Published in Weekly Democrat of Ada, Oklahoma, April 23, 1909 —

The Hitman

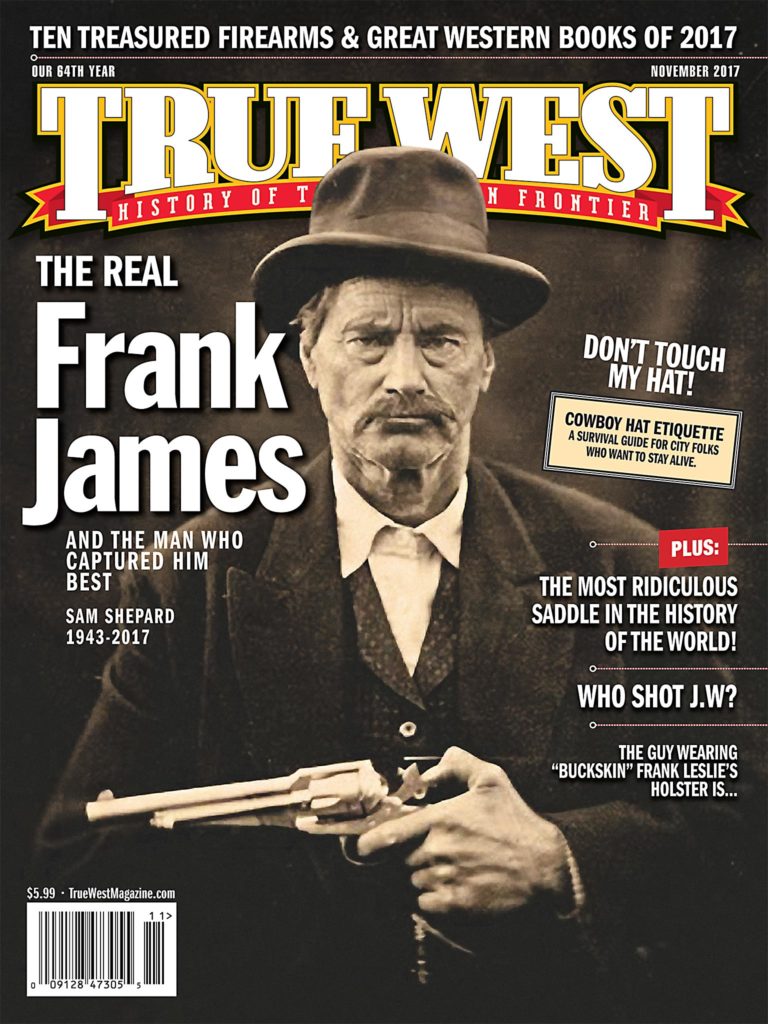

Jim Miller. The hitman was living in Fort Worth at the time of J.W.’s assassination. He was not yet known for his most famous hit, at least, according to some historians—killing Billy the Kid’s killer, former Lincoln County Sheriff Pat Garrett, in 1908.

In 1904, Pap helped Miller beat a charge for murdering former Deputy U.S. Marshal Frank Fore, who a mortgage company had hired to investigate Miller’s forged land titles. Pap testified he saw Miller kill Fore in self-defense. The jury returned a not guilty verdict.

After Miller’s acquittal, evidence pointed to Miller killing Deputy U.S. Marshal Ben Collins. Marshal Jack Abernathy tracked down Miller in August 1906.

Since Miller surrendered peaceably, Abernathy did not shackle his prisoner during the train ride to the jail in Guthrie, Oklahoma. Warming to the marshal, Miller boasted about murder charges he had beaten. Miller refused to elaborate, until Abernathy assured him any admissions would be off the record.

“Who was the hardest man to kill in your experience?” Abernathy asked.

“Jim Jarrott,” Miller replied, adding he shot the unarmed victim five times.

Miller again dodged the hangman’s noose when the court dismissed his murder charge. But not forever.

On February 27, 1909, two days shy of the one-year anniversary of Garrett’s assassination, ex-Deputy U.S. Marshal Gus Bobbitt was killed, near Ada.

The case against Miller was not resolved in court. On April 19, a mob stormed the jail and grabbed the four accused murderers. Although no known published accounts about the lynching quote Miller’s last words, when the noose slipped around Miller’s neck, popular lore claims he said, “Let ’er rip.”

“He Gave His Life for It”

Mollie occupied the homestead for 17 years after J.W.’s assassination, expanding her cattle ranch’s four sections to 16.

In 1933, she learned of Miller’s confession. Abernathy told her after finding out that year his cousin Monroe had married J.W.’s widow, in 1905.

Llano Estacado is vastly different today than it was 115 years ago, when J.W. and his homestead seekers arrived in covered wagons. Before Mollie died in Lubbock in 1960, aged 94, she reflected: “There’s never been anybody who did more for the settlement of this country than Mr. Jarrott, and he gave his life for it.”

This edited excerpt is from Death on the Lonely Llano Estacado, published by University of North Texas Press. Bill Neal practiced criminal law in West Texas for 40 years. He is also the author of Vengeance is Mine: The Scandalous Love Triangle that Triggered the Boyce-Sneed Feud (UNT Press); Getting Away with Murder on the Texas Frontier; and Skullduggery, Secrets, and Murders.