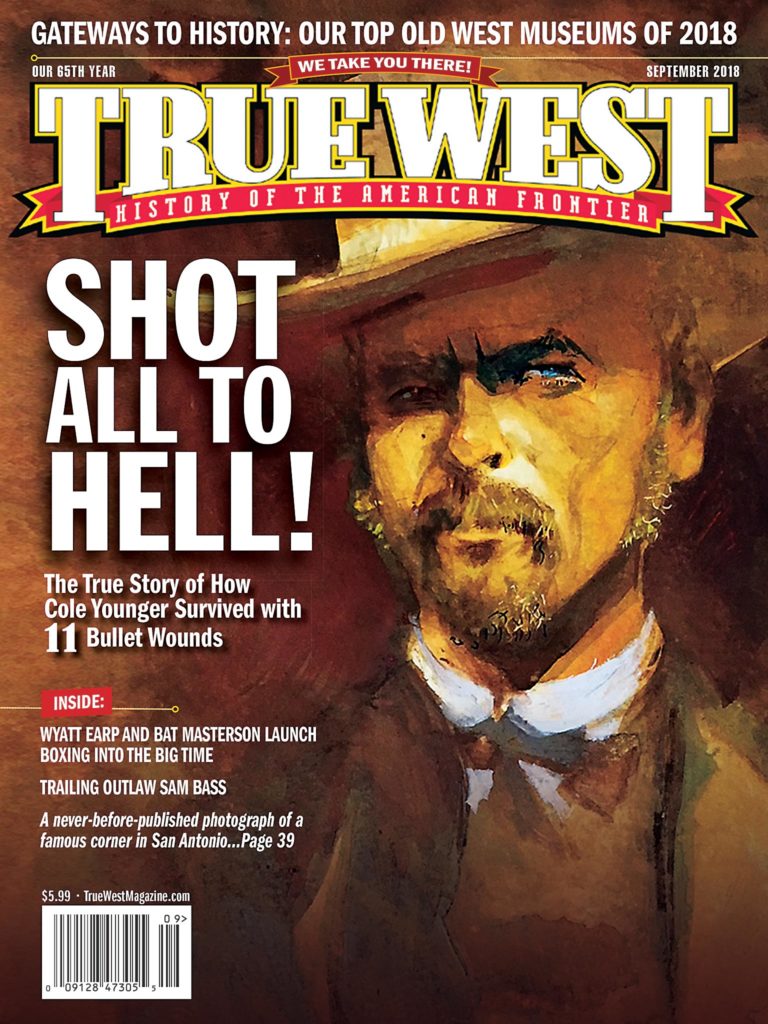

— All Illustrations By Bob Boze Bell —

Tracking the Jamesless-Younger Gang, September 21, 1876

During the two weeks since the botched bank robbery in Northfield, Minnesota, the surviving robbers, believed to be six in number, were pursued through the sloughs and bogs of south-central Minnesota by a series of posses numbering, at times, more than 1,000 men—manhunters every one. A chain of storms washed out the outlaws’ tracks, making it difficult to trail the brigands. The intense pursuit still forced the outlaws

to abandon their mounts near German Lake. A young farm boy named Oscar Sorbel recognized two of the robbers when they passed his father’s farm. After alerting neighbors around Linden Lake, Sorbel made a wild, Paul Revere-style, eight-and-a-half-mile ride to rouse the townspeople of Madelia. Within an hour, two separate posses from Madelia took up the trail and converged on the Watonwan River, south of Lake Hanska.

When the Younger brothers were captured at Hanska Slough on September 21, 1876, after the failed bank robbery in Northfield, Minnesota, a reporter from St. Paul’s Pioneer Press visited the Youngers in Madelia as they recovered from their wounds. Bob Younger told him, “I had tried a desperate game and lost. We are rough boys, used to rough work, and we must abide by the consequences.”

The reporter had first stopped in to see Cole and James, who the doctor would not allow to talk much. Cole managed to say only that he thanked the citizens of Madelia for treating them with kindness.

Cole, the eldest of the Younger brothers, would be portrayed by a newspaperman who knew Frank James, Robertus Love, as a man whose bravado proved bulletproof: “Thomas Coleman Younger, who looked like a bishop and fought like a Bengal tiger, lay upon the ground soaked with rainfall and with his own blood—and smiled as he saw approaching him Colonel Vought of the Flanders House at Madelia, hot rifle in hand.”

The Younger brothers had stayed there prior to the Northfield Raid.

“How are you, landlord?” Cole asked.

Cole could see only out of his left eye. He had been struck by a rifle ball under his right eye, which destroyed the optic nerve.

The “devotion of the brothers” was cited as the reason why the Youngers had not escaped. “[Jim Younger’s] mouth was so badly shattered and the hemorrhage was so profuse that it left a trail of blood that was easily followed. At last he became so weak that it was necessary for Cole and Bob to ride beside him to support him. By this they were delayed several days and in the meantime the country was swarming with their pursuers.

“Jesse James objected and remarked to Cole that their trail could be followed by a blind man, and as they of course did not want Jim to fall in the hands of their pursuers, they had better dispose of him and end his sufferings as his death was certain anyhow.

“Bob and Cole looked at James and Frank replied, calling him a cold-hearted villain, a monster with whom he could never associate again, and adding that he would stay by his brother until he died and would then carry his body as far as he had strength to make it possible. This was the reason for the separation of the party…the Jameses left and escaped,” The Cincinnati Enquirer reported Bob saying in an earlier interview while reporting on Bob’s death from tuberculosis on September 16, 1889.

Cole would outlive both his brothers. After he and Jim were released from prison in 1901, Jim committed suicide the following year. Cole outlived Jesse James, killed by Bob Ford in 1882, and Frank James, who died in 1915, but, beforehand, in 1903, had lectured with Cole on a tour of the South. Cole died the next year, on March 21, 1916, in his hometown of Lee’s Summit, Missouri.

Hanska Slough Shoot-Out

What had led up to the Youngers’ capture?

The three brothers, along with cohort Charlie Pitts, were fleeing the failed First National Bank robbery in Northfield, Minnesota. They slipped into a slough, on foot, and disappeared in a dense tangle of wild plums and vines.

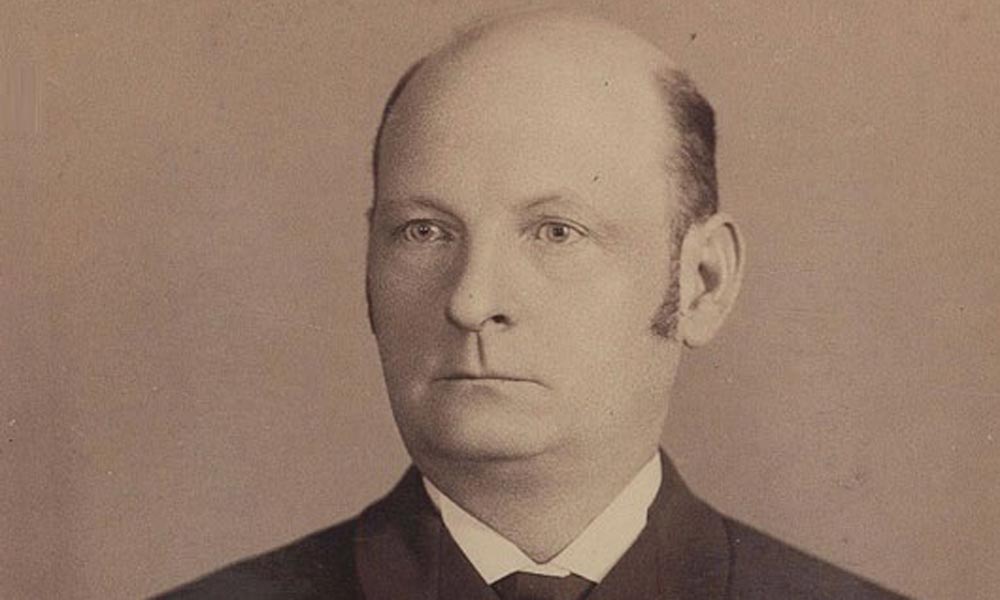

The uproar over the robbery attempt had unleashed anywhere from 40 to 150 citizens on the scene. Surrounding Hanska Slough, Watonwan County Sheriff James Glispin and Capt. William W. Murphy asked for volunteers to help them flush out the desperados. Five men stepped forward—Col. T.L. Vought, Ben M. Rice, George A. Bradford, C.A. Pomeroy and S.J. Severson.

The posse made its way into the river bottom, spread out at 15-foot intervals and scanned the soggy ground ahead of them. They wanted the culprits to surrender and were only to shoot if shot at.

As the manhunters approached where Pitts and the Younger brothers had hunkered down, Pitts said, “We are surrounded. We had better surrender.”

Cole replied, “Charlie, this is where Cole Younger dies.”

“All right, Captain. I can die just as game as you can,” Pitts responded. “Let’s get

it done.”

With those words, Pitts stood and fired.

Sheriff Glispin dropped to one knee and fired back, hitting Pitts in the chest. The posse lit up the thicket with smoke from their blackpowder rifles.

The Youngers struck back, hitting a couple of the possemen.

When the sheriff yelled out, “Hold the line!” the smoke cleared and gunfire paused.

“I surrender. They’re all down but me!” said a voice from the thicket.

Glispin yelled out to his men to hold their fire and ordered the outlaw to step out with his hands high. When the voice responded he couldn’t because his arm was broken, the sheriff told him to raise what he got.

Bob Younger hobbled out, waving a bloody white handkerchief in his left hand. A shot from the bluff above, where others had stayed behind as the seven-man posse crashed through the brush, ripped through the trees, hitting the youngest Younger.

“I was surrendering,” Bob moaned, “and you shot me.”

The pissed-off sheriff yelled out, “I told you to hold your fire! I’ll kill the next man who shoots!”

Hanska Slough fell deadly silent. Glispin and Murphy, followed by the five possemen, passed into the thicket and found the outlaws in contorted poses.

The manhunters kicked away pistols from the robbers’ hands. One of the robbers stared up at nothing; Charlie Pitts had died game.

Cole sat up on one elbow, belligerent and woozy, like a bear awakened from a long hibernation. “Come on,” he sputtered, “I’ll fight any two of you sons of bitches.”

He tried to stand, but he couldn’t. With his one good eye, he leered at the manhunters and said, “I’ll take on any two of you bastards in a fair fight!”

Bob moaned, “Give it up, Cole, or they’ll hang us for sure.”

“What’s the difference if we hang tomorrow or today?” the big bear of a man bellowed. “Let’s get it done.”

Just then, a lumber wagon crashed through the underbrush, to transport the outlaws, defusing the situation.

As the wagon lurched onto the road, spitting mud from its laden wheels like an overloaded manure spreader, the clear light showed the manhunters just how badly their game was shot up.

Sheriff Glispin put his hand on Jim’s shoulder and said, “Boys, this is horrible, but you see what lawlessness has brought to you?”

Cole may have shuddered internally at hearing that, looking at Jim, who appeared to be at death’s door. Jim had been returning home from visiting an uncle in California when he just happened to run into his brothers on a train in Council Bluffs, Iowa. Cole had urged him to join them and, thus, Jim ended up as part of the Northfield and Madelia fiascos.

Patriotic Musings

Cole, of course, did not die that day. After serving 25 years in prison, Cole returned to his native Missouri in February 1903 and shed his outlaw ways.

Within a month, Cole had written up his autobiography. Since book sales were poor, he decided to start up a Wild West show with a surprising partner, Frank James, who, with his brother Jesse, had left the Younger brothers behind to meet their downfall.

The show ended up being a disaster, and, in November, Cole had to pull his pistol on one of the show owners to get the two of them released from the tour.

Frank returned to the family homestead where he grew up, and Cole took on a few gigs before he began the life he always had said he was meant to live: preacher.

Cole had revealed as much while he was in prison, in 1880, when author J.W. Buel asked him about his prison duties. “I occupy much of my time in theological studies for which I have a natural inclination,” Cole said. “It was the earliest desire of my parents to prepare me for the ministry, but the horrors of war, the murder of my father, and the outrages perpetrated upon my poor old mother, my sisters and brothers, destroyed our hopes so effectually that none of us could be prepared for any duty in life except revenge.”

Cole’s affiliation now was the church of life, and he embarked in 1909 on a lecture tour to share “What My Life has Taught Me.” Patriotism was a major feature of his speech.

“A man may be an outlaw, and yet a patriot,” he said. “There is the outlaw with a heart of velvet and a hand of steel; there is the outlaw who never molested the sacred sanctity of any man’s home; there is the outlaw who never dethroned a woman’s honor or assailed her heritage; and there is the outlaw who has never robbed the honest poor.”

Touching on his notorious robberies and capture, he said, “I am not exactly a lead man, but it may surprise you to know that I have been shot between 20 and 30 times and am now carrying over a dozen bullets which have never been extracted. How proud I should have been had I been scarred battling for the honor and glory of my country. Those wounds I received while wearing the gray, I’ve ever been proud of, and my regret is that I did not receive the rest of them during the war with Spain, for the freedom of Cuba and the honor and glory of this great and glorious republic…. Yes, I was in prison then, and let me tell you dear friends, I do not hesitate to say that God permits few men to suffer as I did, when I awoke to the full realization that I was wearing the stripes instead of a uniform of my country.”

He spoke on how prison could redeem a man: “For a man who has lived close to the heart of nature, in the forest, in the saddle, to imprison him is like caging a wild bird. And yet imprisonment has brought out the excellencies of many men. I have learned many things in the lonely hours there. I have learned that hope is a divinity; I have learned that a surplus of determination conquers every weakness; I have learned that you cannot mate a white dove to a blackbird; I have learned that vengeance is for God and not for man. . . . I have learned that the honor of the republic is put upon the plains and battled for.”

He encouraged patriotism in times of peace: “There are times when I think the American people are not patriotic enough. Some think patriotism is necessary only in time of war, but I say to you it is more necessary in time of peace.

“When the safety of the country is threatened, and the flag insulted, we are urged on by national pride to repel the enemy, but in time of peace selfish interests take the greater hold of us, and retard us in our duty to country.

“It may be presumptuous of me to proffer so many suggestions to you who have been living in a world from which I have been exiled for 25 years….

“I hope to be of some assistance to mankind and will dedicate my future life to unmask every wrong in my power and aid civilization to rise against further persecution. I want to be the drum-major of a peace brigade, who would rather have the good will of his fellow creatures than shoulder straps from any corporate power.”

Most important, he wanted to make sure others did not follow his path: “There is no heroism in outlawry, and the fate of each outlaw in his turn should be an everlasting lesson to the young of the land.”

When Cole shared why he had written his autobiography, which featured material he used in his lectures, he stated, “In this account I propose to set out the little good that was in my life, at the same time not withholding in any way the bad, with the hope of setting right before the world a family name once honored, but which has suffered disgrace by being charged with more evil deeds than were ever its rightful share.”

Had Cole died on September 21, 1876, he never would have had the chance to tell his side of the story.

Seven Uncommon Men

These members of the Madelia posse shot it out with the robbers at Hanska Slough. Each man received $246 for their efforts. (From left) Sheriff James Glispin, Capt. William W. Murphy, George A. Bradford, Ben M. Rice, Col. T.L. Vought, C.A. Pomeroy and S.J. Severson.

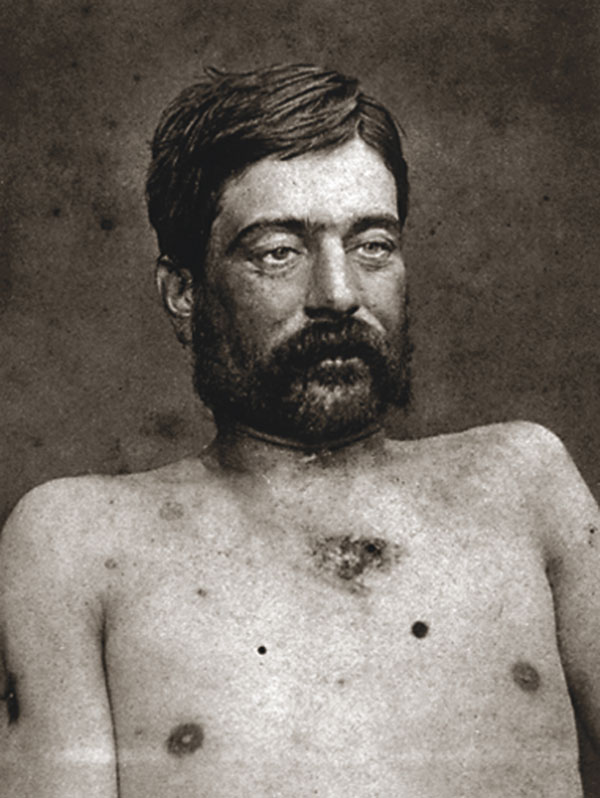

Cole Younger’s Wounds

At Hanska Slough, a ball entered just behind the angle of the right side of Cole’s jaw, passing over the palate arch and lodging in the left side of the upper jaw. He also had four bullet wounds in the back, whether they were received at Northfield or Hanska Slough is unknown. Buckshot penetrated his left shoulder blade, another two inches below, both lodging in fleshy parts and two inches deep. Another entered the middle third of his arm, passing upwards two inches; still another passed behind the armpit. His feet were painful to the touch, and his toenails came off when his boots were removed.

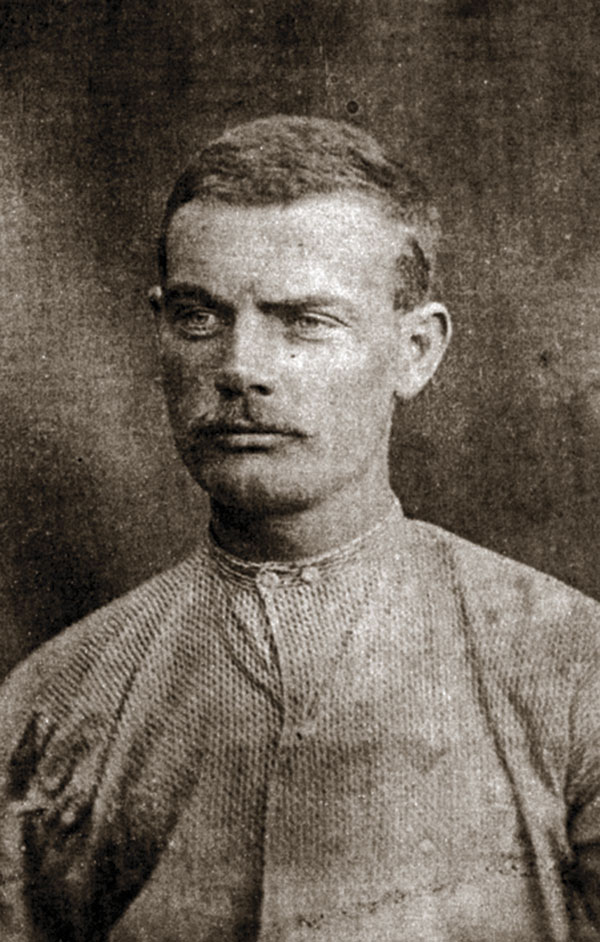

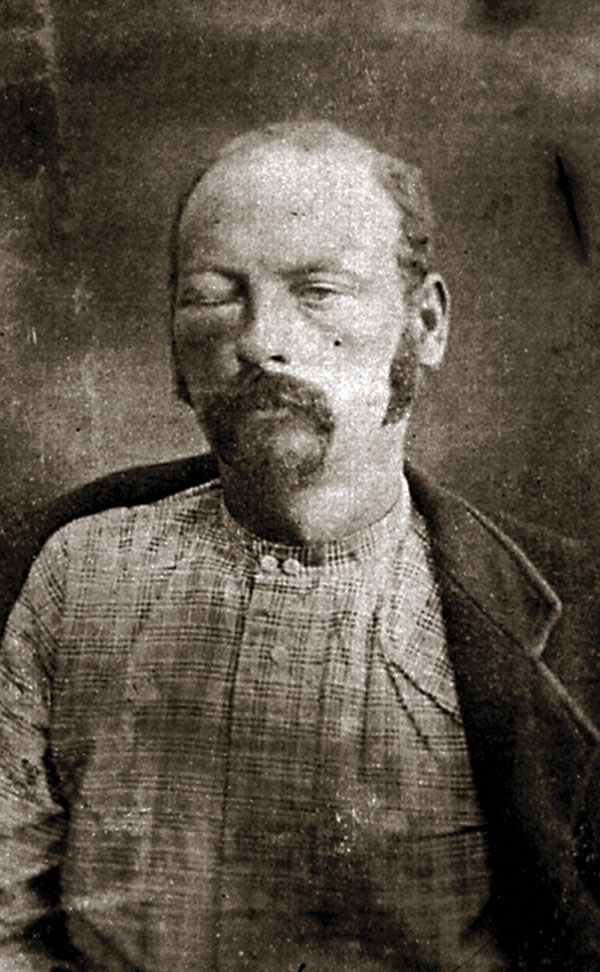

Jim Younger’s Wounds

A ball entered the center of Jim’s upper jaw, destroying nearly half of the upper jawbone. Witnesses later saw pieces of his jawbone removed showing two or three double teeth. His upper lip was swollen and the inside of his mouth was sore, making it difficult for him to speak. Jim was also hit by buckshot in the fleshy part of his middle thigh. A doctor gave him and the other Youngers opiates to help them sleep.

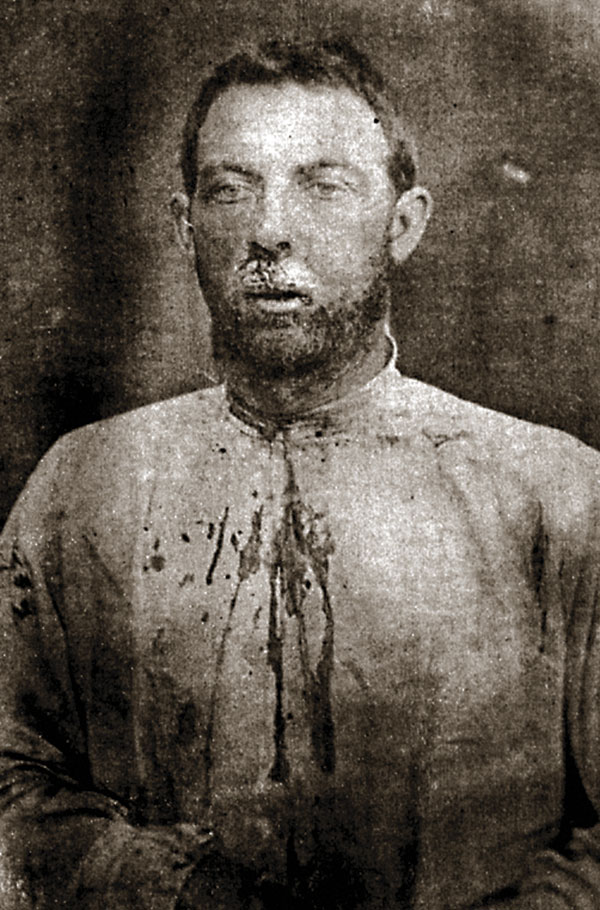

Bob Younger’s Wounds

In Hanska Slough, Bob was hit by a ball that entered just below the right side of his shoulder blade, passed around the body and exited near the nipple. His broken arm, which he sustained in Northfield, was nearly healed by the time the doctor examined him. A large man, light complexioned, no beard and, at his capture, his face recently shaved, Bob was intelligent, shrewd and not as communicative as either of his two brothers.

— Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin —

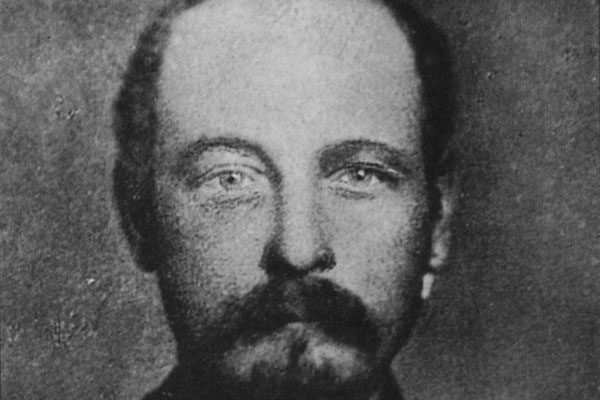

Charlie Pitts’s Wounds

Charlie was six feet tall, 175 pounds, with thick black hair and a heavy moustache and goatee. The fatal bullet entered his left breast, one inch from the center of the breastbone and approximately three inches from the neck. Pitts’s corpse was shipped to St. Paul and displayed in the west wing of the capitol. Over 2,000 of the curious paid 10 cents each to file past the dead robber.

https://truewestmagazine.com/the-battle-of-northfield/