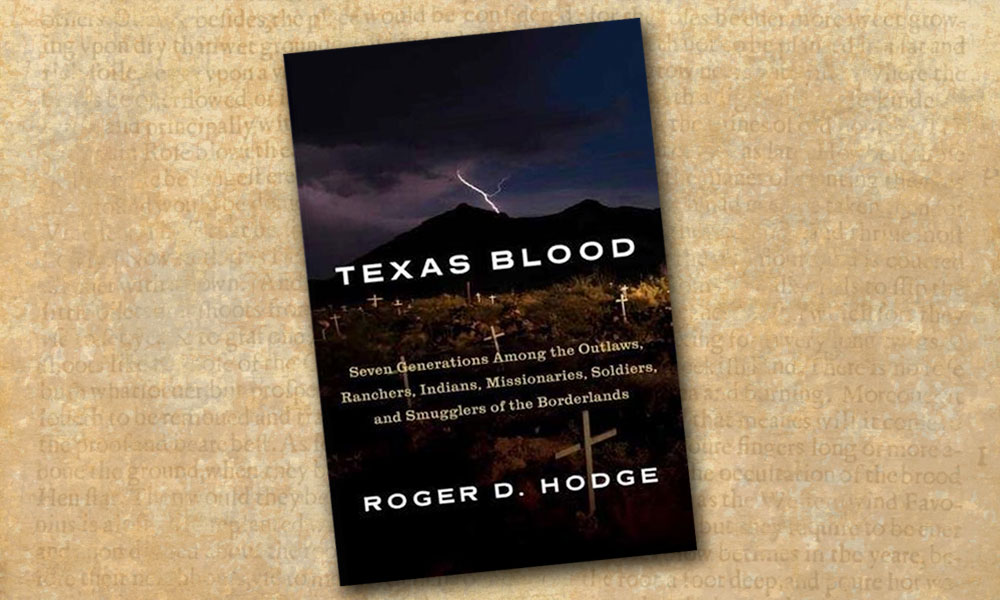

Four years after Philipp Meyer’s multi-generational Texas novel, The Son, was published, and subsequently developed by the best-selling author as a series for AMC television, Brooklyn author and Texas native Roger D. Hodge has done the enigmatic Meyer one better: he has published a generational autobiography of his family’s history: Texas Blood: Seven Generations Among the Outlaws, Ranchers, Indians, Missionaries, Soldiers and Smugglers of the Borderlands (Alfred A. Knopf, $27.95).

Hodge, who grew up a rancher’s son in the hardscrabble and ever-more violent border town of Del Rio, Texas, before leaving for college in Tennessee in 1985 (“unconsciously reversing my family’s long-ago westward migration,” he says), has written the first major sequel to Patricia Nelson Limerick’s two masterly reinterpretations of Western history—The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West and Something in the Soil: Legacies and Reckonings in the New West—and edited, with Clyde A. Milner II and Charles E. Rankin, a book of essays titled Trails: Toward a New Western History. Hodge’s epic saga simultaneously acts as an extension of Limerick’s New Western history philosophy. In her Trails essay titled “What on Earth is New Western History?,” she writes, “…the most fundamental mission of the New Western History is to widen the range and increase the vitality of the search for meaning in the western past.”

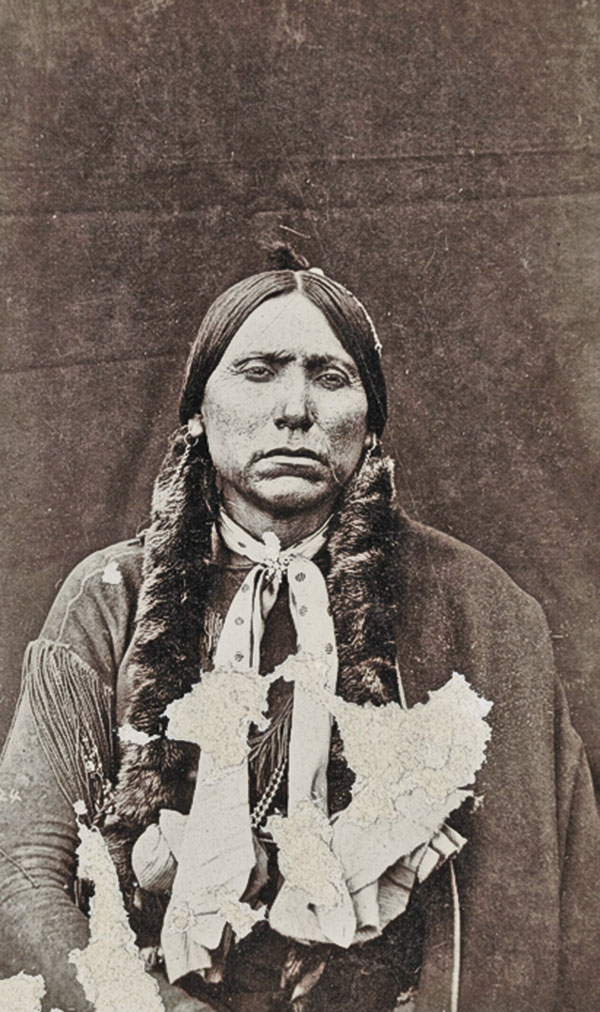

In Texas Blood, Hodge effortlessly blends his personal life-experiences, family genealogy and American history into the perfect synthesis of Old West and New Western history: “Before the late nineteenth century, when the Plains Indians were finally pacified—that is, conquered and exiled to reservations in Oklahoma—west of the Balcones was the Comanche empire; east toward the gulf lay the Anglo settlement in thin bands along the rivers. And as I was eventually to discover, that fault zone also happened to trace, with uncanny accuracy, a partial map of my ancestors’ nineteenth-century peregrinations.”

— Courtesy Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library —

Will Roger Hodge’s blend of history, family legacy and personal musings and criticisms on the current state of the American West effectively change a reader’s mind about what the West was, is and might be? I cannot make any assumptions, but if the buyer is not philosophically inspired to self-contemplation and reckoning of one’s own personal—and familial—history in the West, then Hodge’s passionate eulogy of Steinbeckian proportion is beyond the reader’s comprehension. And, like authors Cormac McCarthy, Max Evans, Larry McMurtry, William Least Heat Moon, Edward Abbey, Colin Fletcher, John Steinbeck and J. Frank Dobie, who have found inspiration in the past and present to muse on the West before them, Hodge shares his observations with a keen sense of place. “Like all American landscapes, that of West Texas is a palimpsest of lost and vanishing lifeways. Yet the aura of a potent mythology lies heavily upon the land and exerts a fascination that defies easy analysis; it draws new blood, new life, to refresh the thorny countryside.”

The former editor of Oxford American and Harper’s Magazine, Hodge’s extended family saga of Texas and the West follows a tradition of American travel writing that has its roots as far back as Alexis de Tocqueville’s On Democracy in America and as recent as Rinker Buck’s The Oregon Trail: A New American Journey. Texas Blood should inspire readers to read or reread recent and past classics of the West that bridge eras and genres, including Paul Andrew Hutton’s The Apache Wars, John Boessnecker’s Texas Ranger: The Epic Life of Frank Hamer, the Man Who Killed Bonnie and Clyde, S.C. Gwynne’s Empire of the Summer Moon, Alan Weisman and Jay Dusard’s La Frontera: The United States Border with Mexico, Tom Miller’s On the Border, William Least Heat Moon’s Blue Highways and J. Frank Dobie’s A Vaquero of the Brush Country: The Life and Times of John D. Young. While Hodge’s writings will never be equated with the literary lyricism of Laura Ingalls Wilder, Wallace Stegner or Mari Sandoz, his honest and self-reflective tale of his family’s legacy in the West will endure and inspire awe, just like his beloved—and bedeviled—Big Bend of the Rio Grande.

—Stuart Rosebrook