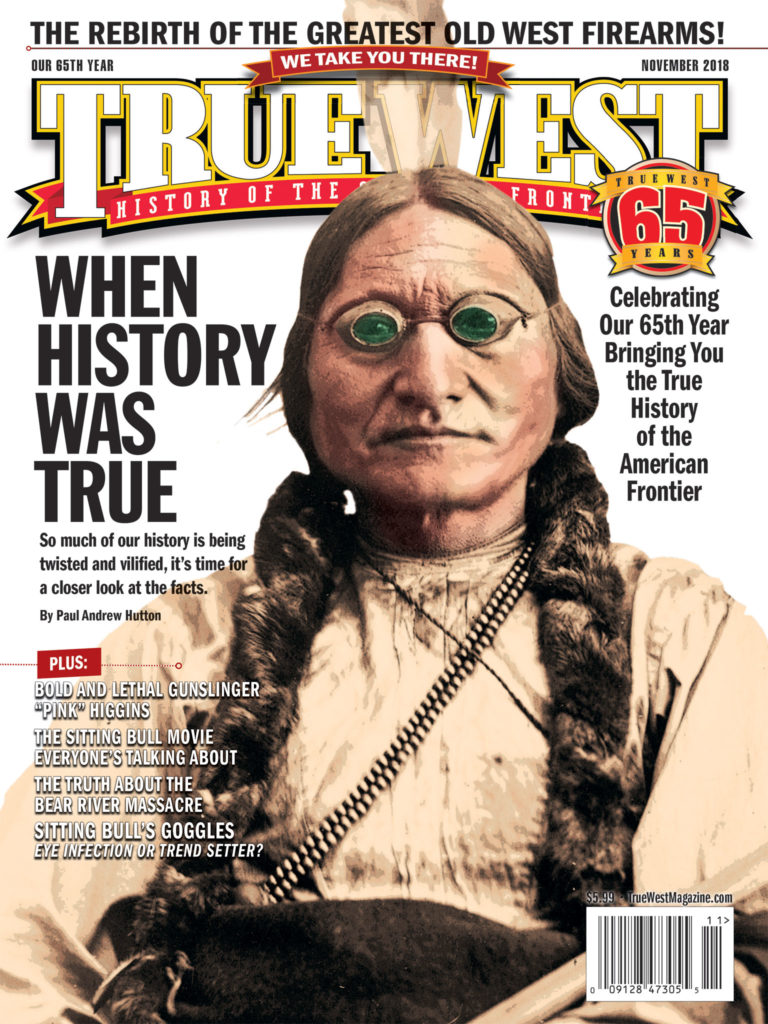

— Courtesy LDS Church Archives —

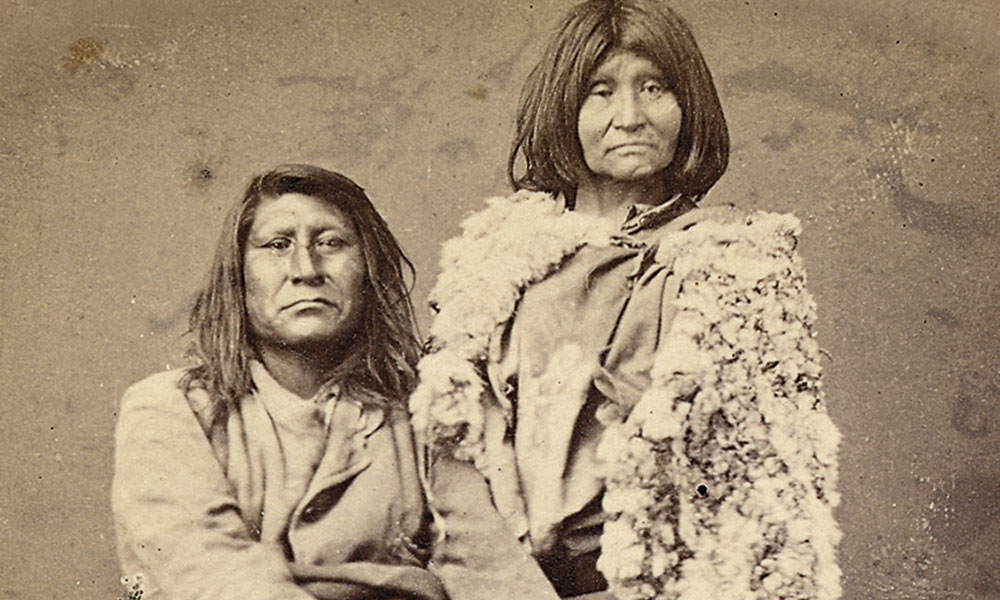

On January 29, 1863, Sagwitch Timbimboo stepped out of his lodge in pre-dawn darkness and sub-zero cold. He stood in the Northwestern Shoshone winter camp along Beaver Creek, where it cut through bluffs lining the Bear River at the northern end of Cache Valley in what is now southeastern Idaho.

Off to the east, perhaps a mile from the village, Sagwitch sensed activity on the face of the steep bluffs. Having heard reports of soldiers coming, he realized the cavalry had arrived and were even now crossing the ice-choked waters of the Bear River.

Before the morning ended, Sagwitch would find himself crossing the same frigid stream with a bullet-shattered hand, seeking escape from the worst massacre of American Indians by the U.S. Army in the history of the West.

Miner Mishap

Sagwitch knew he must warn the roughly 75-lodge village. A few weeks before, hundreds more Shoshones had gathered there to celebrate a Warm Dance to invite spring. On January 8, with the celebration underway, a wandering group of Shoshone braves killed a miner in a group traveling from the Grasshopper mines in Montana Territory to Utah Territory’s Salt Lake City.

Upon reaching the city, the miners went to the law. Chief Justice John F. Kinney handed a warrant to “Marshal Isaac L. Gibbs, for the arrest of Bear-hunter, Sandpitch and Sagwitch, chiefs of a band of several hundred warriors, now inhabiting Cache Valley,” The Deseret News reported.

The attack on the miners likewise upset the Shoshone encampment. Mae Parry, Sagwitch’s great-granddaughter and a Shoshone historian, gathered oral accounts from tribal elders. In 1976, she wrote:

“[T]he Indians were getting restless. They could feel that trouble was going to start soon.”

Then, Parry added, an old man named Tin Dup dreamed “he saw his people being killed by the pony soldiers. He told the Indians of his dream and told them to move out of the area…. Some families believed Tin Dup’s dream and moved, thus sparing their lives.”

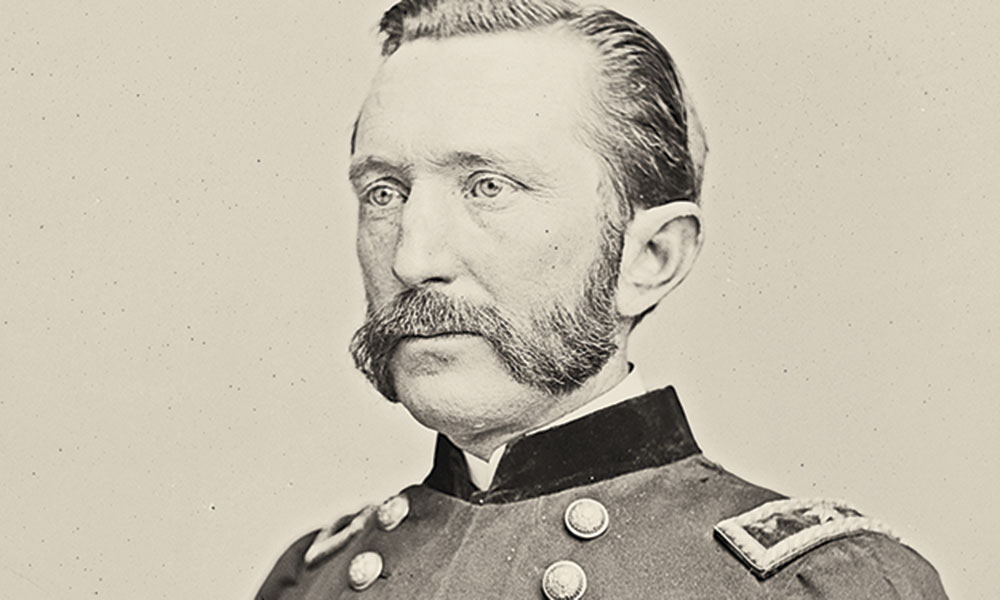

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

Take No Prisoners

Back in Salt Lake City, Gibbs turned for help from Col. Patrick Edward Connor, commander at Camp Douglas. Connor, bristling for a fight, wrote to the Army’s Department of the Pacific:

“Chief Justice Kinney, of Great Salt Lake City, made a requisition for troops for the purpose of arresting the Indian chiefs Bear Hunter, San Pitch, and Sagwitch. I informed the marshal that my arrangements for our expedition against the Indians were made, and that it was not my intention to take any prisoners, but that he could accompany me.”

On January 22, Connor sent some 70 infantry troops and 15 supply wagons north, under the guise of escorting a wagon train of grain back from Cache Valley. Late in the evening of January 24, Connor led 275 cavalry troops and officers head-on into withering north winds. He drove the column hard, making 68 miles before stopping in Brigham City. Some 75 frostbitten men could not go on when the expedition pushed through the snowbound mountains and into the south end of Cache Valley.

Connor sent the foot soldiers and wagons on a night march north to Franklin, the last of the Mormon settlements in the valley, just beyond Utah Territory’s indistinct border. The Shoshone winter camp lay some 12 miles farther.

Between Franklin and the Bear River bottoms, Connor and the cavalry overtook the wagons, mired in deep snow. Fearing the loss of surprise, Connor sent Maj. Edward McGarry and the cavalry to surround the camp and wait. Crossing the icy Bear River left some troopers unhorsed and drenched, and all cold and soaked.

Sagwitch, with Bear Hunter and other chiefs, readied the Shoshones for battle, but Sagwitch urged caution. He assumed the soldiers would demand the surrender of the men who had attacked the miners. But others would not wait. A few mounted warriors paraded across the snowy flatland between the river and the village, taunting the soldiers.

McGarry, infamous for his hot temper, ordered a charge rather than following orders. Most of the 14 soldiers killed, and 46 soldiers and four officers wounded, likely fell in the initial attack on a Shoshone position protected by the banks of the ravine and thick willows. When Connor arrived, he sent troops to flanking positions, eventually surrounding the village. Then the fighting, and the slaughter, started in earnest.

Connor congratulated his troops upon their return to Camp Douglas, as recorded in The Deseret News: “At daylight on the 29th of January, 1863 you encountered the enemy greatly your superior in numbers, and in a desperate battle, continued with unflinching courage for over four hours, you completely cut him to pieces, captured his property and arms, destroyed his stronghold, and burned his lodges.”

Fighting did continue for four hours as Connor claimed, but the “desperate battle” ended quickly. Only by including noncombatants could the Shoshones be considered “superior in numbers.”

The Butcher & His Volunteers

The Indians had few firearms and little ammunition. “[W]hat was an arrow compared to the muskets of the army,” Parry wrote. “The Indians were being slaughtered like wild rabbits, Indian men, women, children and babies were being slaughtered left and right. No butcher could have murdered any better than Colonel Connor and his vicious California Volunteers.”

Sixteen days after the fight, while recovering from frostbitten feet at Camp Douglas, Sgt. William L. Beach set down an account and detailed map, outlining the battle that became a massacre.

After orders to attack, the men kept up the fight on their own, as Beach wrote: “no officer was heeded or needed[.] The boys were fighting Indians and intended to whip them. It was a free fight every man on his own hook.”

Soldiers rushed “into their very midst when the work of death commenced in real earnest. Midst the roar of guns and sharp report of Pistols could be herd [sic] the cry for quarters but their [sic] was no quarters that day…. The fight lasted four hours and appeared more like a frolick [sic] than a fight….”

The most reliable estimates of Shoshone deaths range from 250 to 350. Soldiers raped, tortured and mutilated women and children. Some of them escaped.

“The Northwestern Shoshones were jumping into the river and trying to escape by swimming across the river,” Parry wrote, including women who “swam with babies upon their backs. Most of them died.”

Chief Bear Hunter was killed by the thrust of a red-hot bayonet through his head. At the urging of his people, “Chief Sagwitch escaped with a wound in his hand, after having two horses shot from under him,” Parry wrote.

Sagwitch’s oldest son, Soquitch, escaped. His youngest, two-year-old Beshup, survived seven gunshot wounds. A 12-year-old son, Yeager, escaped death by playing dead among the corpses. Sagwitch’s wife and at least two of his children died.

Surviving Shoshones—some 160 of them, Connor reported—were left to fend for themselves without food or shelter when the military quit the field with their plunder, including about 175 horses.

— Courtesy LDS Church Archives —

Declaring Peace

In the months following the massacre, Sagwitch and as many of the scattered Northwestern Shoshones as he could gather raided throughout northern Utah Territory, stealing stock and killing several settlers.

Seeking an end to hostilities, James Doty, Utah territorial governor and superintendent of Indian affairs, sought out Sagwitch and other Shoshone leaders.

On July 30, Doty informed the Army: “A treaty of peace was this day concluded…with the bands of the Shoshones, of which Pocatello, San Pitch, and Sagwich [sic] are the principal chiefs. This information is given that these Shoshones may not be injured when met by troops, if they are at the time behaving themselves well.”

While agreeing to the treaty’s terms, Sagwitch did not sign the agreement, as he was recovering from a bullet wound. Army troops had shot him while he was held captive and on his way to finalizing the treaty.

— Jackson photo courtesy National Archives and Records Administration —

Connor—since promoted to general, in recognition of his “gallantry” during the Bear River fight—informed his commander on July 31: “Made treaty with remaining bands of Snake Indians yesterday.”

Over the next decade, Sagwitch’s people struggled, as promised annuities proved insufficient or absent. Mormons continued to settle on traditional tribal lands, the Transcontinental Railroad bisected the Northwestern Shoshone homeland and confusion between Indian agencies in Utah and Idaho Territories complicated life for the wandering bands.

Sagwitch determined that the Mormons, while destroying the Shoshones’ traditional way of life, offered the only hope for a future. Spring of 1873 saw hundreds of Northwestern Shoshones join the Mormons in mass baptismal ceremonies. Most assimilated into Mormon society.

The cultural identity of the band waned. For decades, the only land the Northwestern Shoshones owned was a cemetery. The first grave there was reportedly Sagwitch’s. His headstone claims he died in 1884, but the few surviving records suggest 1886 or 1887.

— Muybridge photo True West Archives —

His People Survive Still

Sagwitch’s descendants have been pivotal in the Northwestern Shoshones’ struggle to retain tribal cohesion; they still occupy leadership positions in the band. Today, the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation has achieved federal recognition, operates several programs to assist its members and is involved in business, cultural and historical initiatives, including acquiring the site of the Bear River Massacre.

Each year, the morning of January 29 finds members of the band and scores of supporters congregating at Bear River to honor Shoshone ancestors who had gathered there for centuries—until the slaughter of 1863 bloodied the ground and nearly eliminated the tribe.

But Sagwitch survived the massacre, and his people survive still.

Rod Miller writes history, fiction and poetry about the West. He is a four-time winner of the Western Writers of America Spur Award.