We live in a time of national discord. Americans find themselves adrift in a cultural malaise highlighted by overheated political rhetoric from all sides; a sad resurgence of racial tensions; unrelenting foreign conflict; a distrust of national institutions; and a callous rejection of a once-cherished American past. We see this in the current dismissal by many (most notably in colleges and universities) of the Anglo-Protestant heritage from the American Revolution and early republic eras; of the once seemingly universal, but now historically bankrupt, “lost cause” nostalgia following the Civil War; and of the grand unifying story of Western expansion.

Jefferson crafted the Louisiana Purchase and extended his ambitions to Spanish possessions in the Southwest as well as British Canada in the north, for he envisioned the West as a refuge for oppressed peoples of the corrupt Old World. Yet the author of the Declaration of Independence has recently been roundly condemned for his unenlightened attitude on race.

The public’s general acceptance of the “winning of the West” has changed considerably since the park was envisioned in 1933 and opened in 1967. The original Gateway Arch museum celebrated the pioneer spirit that conquered a wilderness and built America into a world power; the new museum questions these achievements. Visitors learn that Europeans murdered innocent natives and illegally seized their lands; that women and minorities suffered when the supposedly more enlightened rule of colonial France and Spain was replaced by American rule; and that territorial acquisition by warfare was both illegal and immoral.

Removed from the story is the glory of Westward Expansion, which gave rise to a new world power that destroyed the twin evils of Nazi fascism and Soviet communism in the next century.

Attacks on Frontier Heritage

The Gateway Arch changes are part of a systematic attack on our frontier heritage that has been ongoing for several years.

In 1991, Congress renamed Montana’s Custer Battlefield National Monument as Little Bighorn National Monument. In 2016, South Dakota’s Harney Peak, named for Mexican War hero William S. Harney, was renamed Black Elk Peak, in honor of the Sioux warrior.

You can find a quote by Black Elk at the Little Bighorn battlefield visitor’s center: “Know the power that is peace.” Would a quote from Tojo be fitting on the

monument at Pearl Harbor, historian John Carroll asked. A bit extreme, but Black Elk did participate in the 1876 slaughter of Custer’s command.

Kit Carson remains controversial in New Mexico for his 1863 campaign against the Navajos that led to their tragic removal to Bosque Redondo. To defend Carson is “like trying to rehabilitate Adolf Hitler,” a historian at Navajo Community College declared. Carson’s tombstone in Taos was spray-painted with swastikas and “Nazi” in 1990. Residents recently campaigned to strip his name from the city park where he is buried.

The Arcata, California, city council voted to remove a William McKinley statue because he was a proponent of “settler colonialism.” The 25th U.S. President, who was assassinated in 1901, also had his name stripped from the highest peak in North America (now Denali) in 2015. McKinley had served in the Union army during the Civil War, was an advocate of black rights as both governor of Ohio and U.S. President, and is credited with initiating America’s rise to world power.

Texas joined the battle to eradicate Confederate commemorations to the point of an Austin committee suggesting the city should not be named after Stephen F. Austin because he supported slavery. In San Antonio, the city council and heritage advocates are in a heated tussle over an Alamo grounds redesign that includes removing a 1936 Cenotaph monument that fronts the “Shrine of Texas Liberty.” Academics have denounced the Alamo as a monument for slavery and racism, not liberty.

In June 2018, the American Library Association stripped Laura Ingalls Wilder’s name from the title of its prestigious children’s book award because her books reflect “dated cultural attitudes toward indigenous people and people of color that contradict modern acceptance, celebration, and understanding of diverse communities.”

In July, New Mexico’s Fiesta de Santa Fe caved in to Indian protests and dropped the century-old “Entrada” re-enactment of Don Diego de Vargas’s 1692 reentry into Santa Fe after the 1680 Pueblo Revolt had expelled the Spanish.

An Ancient Prejudice

The dismissal of the West by the East is an ancient prejudice. During colonial times, frontier folks were disdained as dangerous characters of low breeding, prone to democratic anarchy and fits of violence. Politics were controlled by New England and Virginia elites who were still rather similar to their English forbearers.

During the 1820s, Americans began to search for an identity separate from their European ancestors. The powerfully symbolic deaths of Thomas Jefferson and John Adams on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence provided a major impetus; the new generation felt keenly the passing of the revolutionary generation, not unlike the present uneasiness at the passing of the WWII generation. Americans turned to the West in search of new figures to lead the country forward—men who were masters of both a hostile environment and their own destiny.

The 1828 election of Andrew Jackson as U.S. President marked a shift in political power to the new West, ushering in the so-called “Age of the Common Man.” The martyrdom of Davy Crockett at the Alamo and the celebrated explorations of Kit Carson and John Frémont all served to mark bold frontiersmen as ideal Americans.

Jackson’s protégé, James K. Polk, fulfilled Jefferson’s “Empire of Liberty” dream by seizing the American Southwest and California from Mexico, acquiring the Oregon country and achieving the nation’s continental “Manifest Destiny.”

A ghastly Civil War rendered the dream asunder until Abraham Lincoln redeemed it, restored the Union and again turned the nation westward. His Homestead Act and Transcontinental Railroad authorization shaped the new trans-Mississippi West.

Out of this story arose a new epic that united a divided nation and gave a fresh national identity to millions of wildly diverse people coming in from many lands. Dime novels celebrated frontier adventures lived by the first gunfighter “Wild Bill” Hickok, the outlaw James brothers, the frontier Amazon Calamity Jane and Indian fighter “Buffalo Bill” Cody, who took the story on the road in 1883 as a grand Wild West extravaganza that enthralled two generations of Americans and global audiences.

Theodore Roosevelt, author of the magnificent The Winning of the West, kept the West front and center as our first cowboy President. The one-time rancher and famed Rough Rider heralded in bold conservation efforts that reflected a growing awareness that, even at a moment of crowning achievement, something important was also being lost.

The West was won—now what?

Frederick Jackson Turner addressed that question with his 1893 essay “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” He refuted the then-prevailing theory that American institutions had evolved from European “germ cells” without regard to environmental factors. Characterizing the frontier as the “meeting point between savagery and civilization,” he explained the unique American character as a rejection of class and aristocracy, of established religion, standing armies and other European trappings in favor of adaptation, invention, individualism and a rough-hewn democracy. The frontier was not only a process, but also a state of mind.

Turner revolutionized the teaching of American history. By the time of his death in 1932, some 60 percent of history departments in the country’s major universities and colleges taught Western history.

During the 1960s, a new historiography focused on race, class and gender, and obsessed with victimization, came to dominate the academic world and the field of Western history. To these academics, Turner’s West is blind to the horrors of colonialism, hopelessly nationalistic and inherently racist.

What Divides Us

Some of the dismissal of Western history is a result of the glossy froth about the frontier produced after 1900, for Buffalo Bill had seemingly made it all show business.

In 1903, Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery became the first American film to tell a complete story, and the first cinematic Western. By the 1920s, a powerful film industry had emerged, with fully a third of stories devoted to Westerns. By the postwar years, Westerns continued to thrive, adding to movies and literature the new medium of television. It all came crashing down during the 1960s.

The Vietnam War, Watergate and rising environmental and civil rights movements led many Americans to question assumptions that made up our national story. While the decade opened with a burst of optimism heralded by President John Kennedy’s “New Frontier,” it ended with assassinations, racial violence, domestic upheaval, foreign war, bitter political divisions and national despair.

We find ourselves in a similar position today. Emphasizing what divides us allows little room in some circles for a Western story that provides the glue that unites us. That story of struggle, sacrifice and triumph was overly romanticized, but it also made people proud to be Americans, no matter their place of origin. It celebrated the rough democracy that made the rise of a great nation possible. It was a violent story, one that sometimes glossed over injustice, but just as often as not laid bare the sordid truth. The positive far outweighed the negative.

In some ways, this agreed-upon fable was not unlike the tales of Homer, the legends of King Arthur or the epics of Charlemagne that provided identity and pride to a people. Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid became our Achilles and Hector, Jesse James our Robin Hood, while George Custer perfectly played out the part of Roland and the Battle of the Alamo echoed the sacrifice of Leonidas and his Spartans.

The story of the American frontier offers a powerful truth too valuable for our country to cast aside. Embracing that story defines who Americans are as a people. As Pulitzer prize-winning Kiowa novelist N. Scott Momaday wrote: “It has something to do with legend and with the way we must think of ourselves, we cowboys and Indians, we roughriders of the world.”

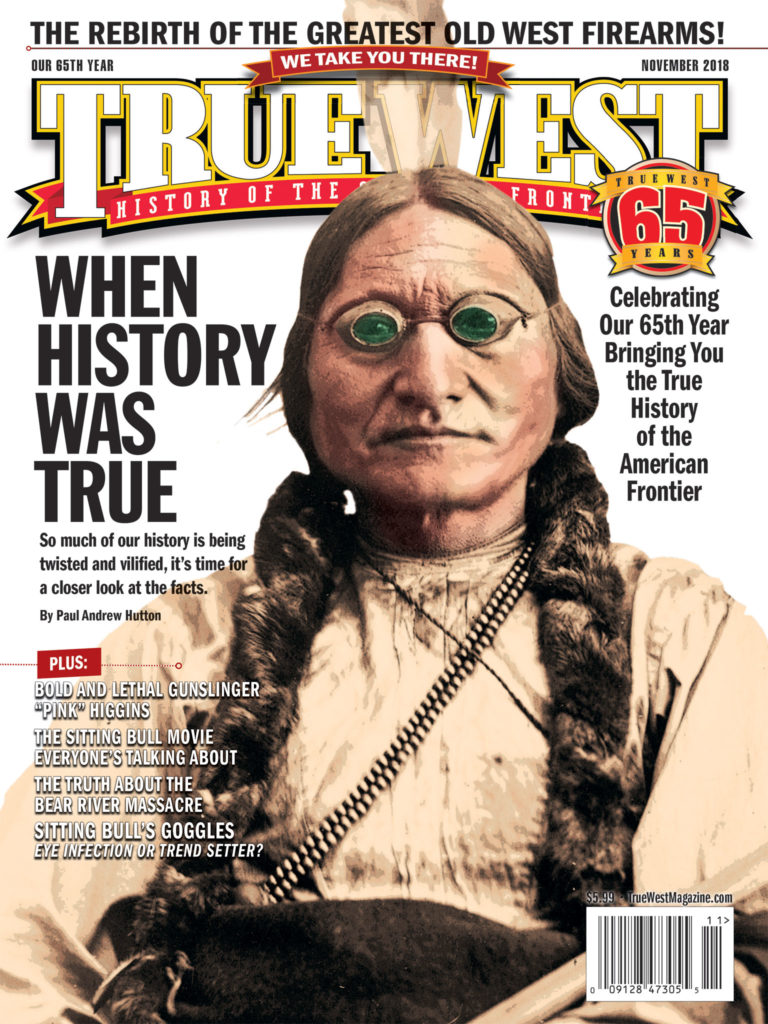

For 65 years, True West has labored to keep the story of the American West alive and relevant. That the magazine has survived into this era of dramatic change in the publishing world is a testament to its success. Under the loving care of Executive Editor Bob Boze Bell and his hardworking staff, True West has adapted to changing tastes, while remaining ever faithful to its core mission.

That mission is one we must all embrace if we are to keep the unifying spirit of the American West alive—for truly a nation that forgets its past has no future.

A Distinguished Professor of History at the University of New Mexico, Paul Andrew Hutton won the Western Writers of America Spur for his most recent book, The Apache Wars: The Hunt for Geronimo, the Apache Kid, and the Captive Boy Who Started the Longest War in American History.

https://truewestmagazine.com/powells-grand-west/