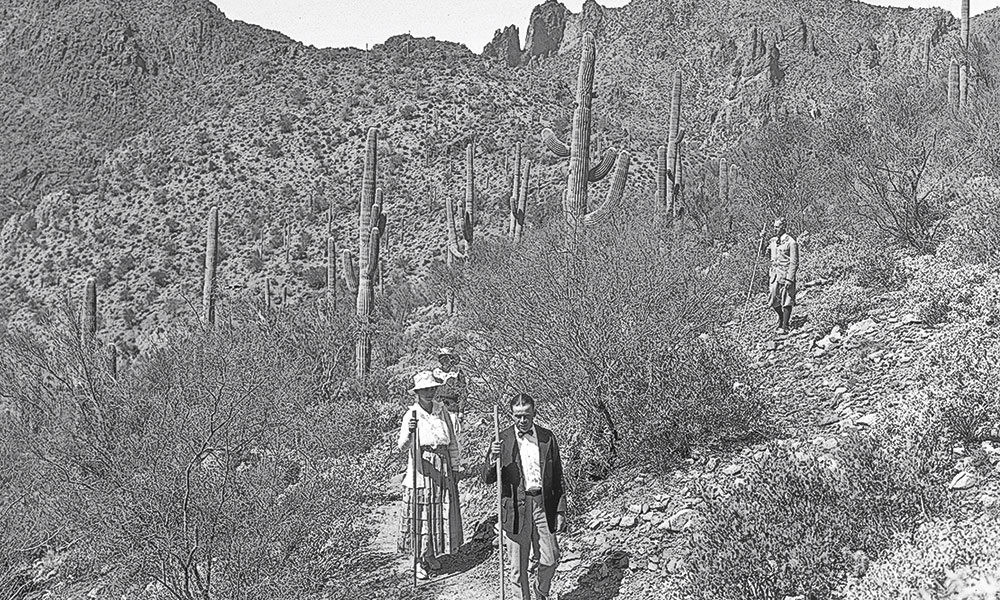

— Courtesy McClintock Collection, Arizona Room, Phoenix Public Library —

In Arizona, few places possess a local mystique as strong as that of Castle Hot Springs.

Located in the southern foothills of the Bradshaw Mountains, approximately 45 miles northwest of downtown Phoenix, Castle Hot Springs acquired its name from geothermal springs flowing within a small valley adjacent to Castle Creek. Credit for the discovery of the springs is attributed to prospector George Monroe, although the springs were likely known to the Yavapai and Tonto Apaches who lived in, or frequently traveled, the area. Stories vary as to the spring’s discovery.

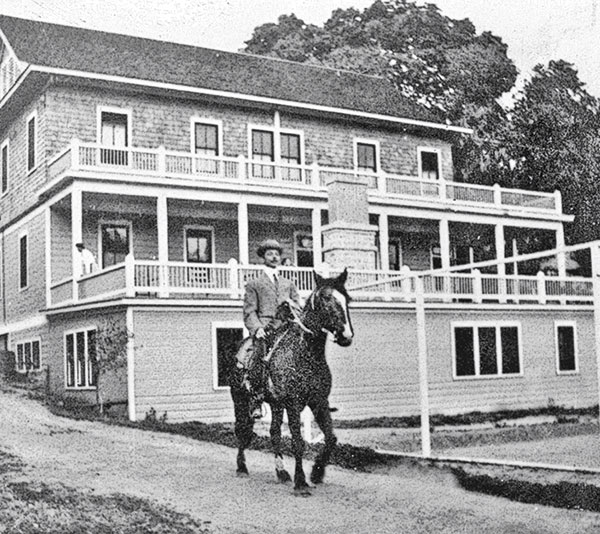

— Courtesy Castle Hot Springs —

A Lovers’ Find?

George was born in Indiana, around 1835, and first came to Arizona Territory in 1862 as a private in the California Volunteers during the Civil War. After an honorable discharge in New Mexico Territory, George returned to Arizona Territory around 1864 and pursued a career as a miner. He spent decades prospecting out of Prescott and Wickenburg, north and south of the mountains, respectively. On some of these sojourns, he was frequently accompanied by his wife, Mollie.

— Courtesy Heritage Auctions, June 13, 2008 —

Mollie, also known as Mary E. Sawyer, was a local legend. Reportedly George’s common-law-wife, she was born in Mississippi in 1846, according to the 1870 census, although other researchers have claimed she was born in New Hampshire. She headed west, supposedly to find a lost love by portraying herself as male prospector Sam Brewer. By the time “Brewer” got to Santa Fe, New Mexico Territory, she discovered her misplaced paramour had been killed in a barroom brawl, so she married a U.S. Army officer who took her to Fort Whipple, just outside of Prescott. When the captain left the fort, Mollie stayed and reportedly met George, around 1870.

Some researchers have given Mollie credit for discovering the springs with George, but that has not been confirmed by the historical record. She was declared insane in 1877 and committed to an asylum for the rest of her life, dying in 1902.

— Cowboys photo Courtesy Castle Hot Springs —

Troops’ Tale

Another unconfirmed story, which did not appear until the second decade of the 20th century, claimed Fort Whipple troops discovered the springs. Around 1867, Col. Charles Craig, the fort’s commanding officer, chased Apaches into the Bradshaws with 168 troops, The Arizona Republican reported in one version on April 6, 1919, in “Castle Hot Springs, Wonder Torrent Wrought by Nature.” The account, written anonymously, stated:

“Standing on the mountain crest surrounded by his officers and men, Colonel Craig looked out over the vast expanse before him, a world of silence where mountain peak succeeded mountain peak, many of which resembled castles, and the glory of the rising sun, battlements and towers gleamed and glistened. Each man held his breath almost expecting to see armored knights and swaying banners come forth from the portals and to hear the flare of trumpets.

—Victorian-era swimming attire photo courtesy Library of Congress —

“Long and earnestly the Colonel gazed at the scene. Into his face and the faces of the men crept the reflection of a sweet and solemn thought, for each in his way, remembered then, having heard at his mother’s knee of a certain ‘new Jerusalem.’

“‘If we find the headwaters of that creek boys, we’ll call it Castle Springs in memory of this’—and removing his hat, the colonel inclined his head as though in reverent acknowledgement of the scene before him.”

— Ladies photo Courtesy Arizona Historical Society —

Though an intensely well-written fabrication, which has been repeated in both short and exceedingly long versions, the Craig story has no veracity. Craig does not appear on the Fort Whipple muster rolls for this time period. Plus, the springs are not the headwaters of the creek, the naming of which dates to at least seven years before the discovery of the springs.

— Courtesy Castle Hot Springs —

Veiled in a Mist

In another story, George was the one being chased by Apaches. Escaping up a ravine, “penetrat[ing] it farther than white man or Indian had gone before,” he discovered the hot springs, George’s 1897 obituary stated.

Yet another story had prospector John Wesley “Poker” Johnson providing directions for a shortcut between Wickenburg and Prescott to George and a few fellow prospectors. Johnson’s knowledge was apparently exaggerated, and the group became lost. After aimless wandering through the mountains, the group came across the springs.

So convoluted were the varying tales that, in George’s 1897 obituary, The Arizona Republican questioned the stories related to the find, noting, “The manner of the discovery is doubtful, for early events in this territory are veiled in a mist that is little better than tradition.”

— Courtesy Castle Hot Springs —

Arizona’s First Health Resort

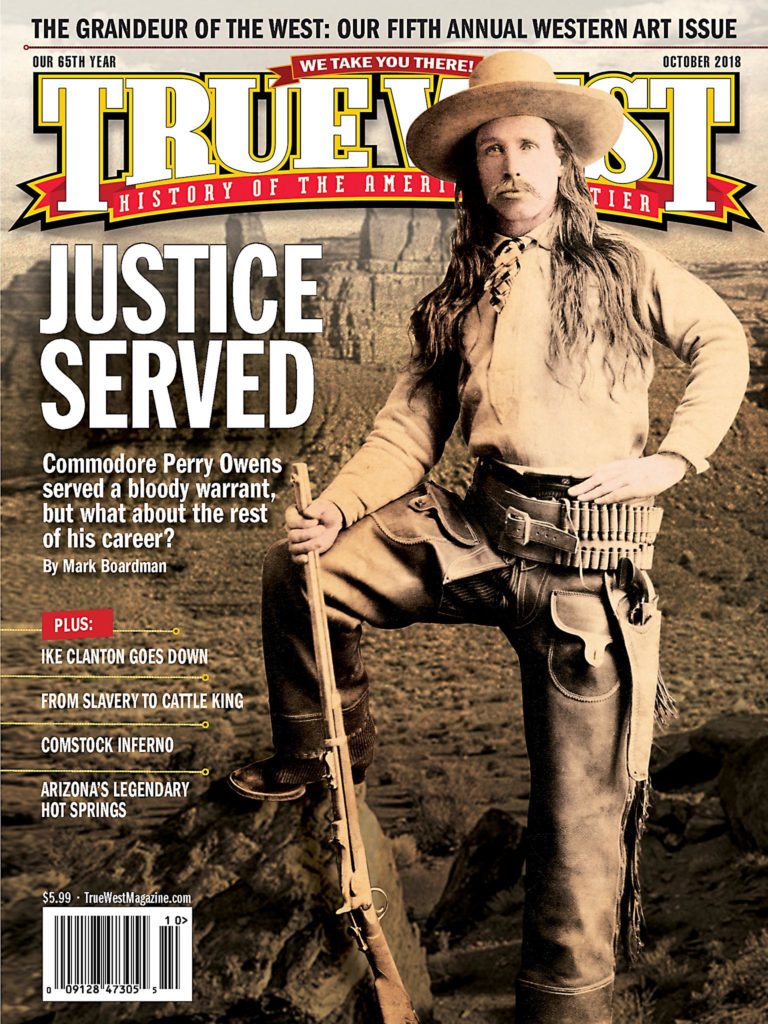

What is verifiable is that Abraham Peeples, a well-known miner in his own right, had the waters tested and filed a preemptive claim for George and three partners in 1874.

George never developed the springs, and they were eventually owned by Thomas Holland, a prospector from Tennessee. Holland brought in an experienced hotelier and set up a hotel at the springs in 1884, which promptly burned down and was rebuilt.

A decade later, the springs attracted mining magnate and entrepreneur Frank M. Murphy. Born in Maine and raised in Wisconsin, Frank and his brother, Nathan Oakes, came to Arizona Territory in the late 1870s.

Shortly after arriving in Prescott, Frank began a stage line in the Bradshaw Mountains, only to lose out to competitor Virgil Earp. During his brief run, however, Frank became active in mining as a prospector, investor and speculator.

— Courtesy Castle Hot Springs —

Nathan Oakes became Arizona’s territorial governor, serving from 1892-1893 and 1898-1902. With assistance from Nathan Oakes and a pair of prominent Philadelphians, Frank purchased Holland’s interests and created Arizona’s first health resort in 1898.

One of Frank’s mining investors was “Diamond Jo” Reynolds, who had set up a railroad spur to Hot Springs, Arkansas, in 1876. As part of his development scheme, Frank, who helped bring the Santa Fe, Prescott and Phoenix Railway to Phoenix, set up a station at Hot Springs Junction (now Morristown), southwest of Wickenburg, and hired railroad engineers to build a road from there to the hotel at the springs.

A road already existed from Phoenix, but Frank, like Reynolds, wanted access from the railroad. In addition to serving the local mining community, the new year-round resort, then-called Castle Creek Hot Springs, wanted to also attract more affluent patrons willing to travel from the east to Hot Springs Junction—some via private Pullman cars—and take a stage to the resort. One such guest was artist Maxfield Parrish.

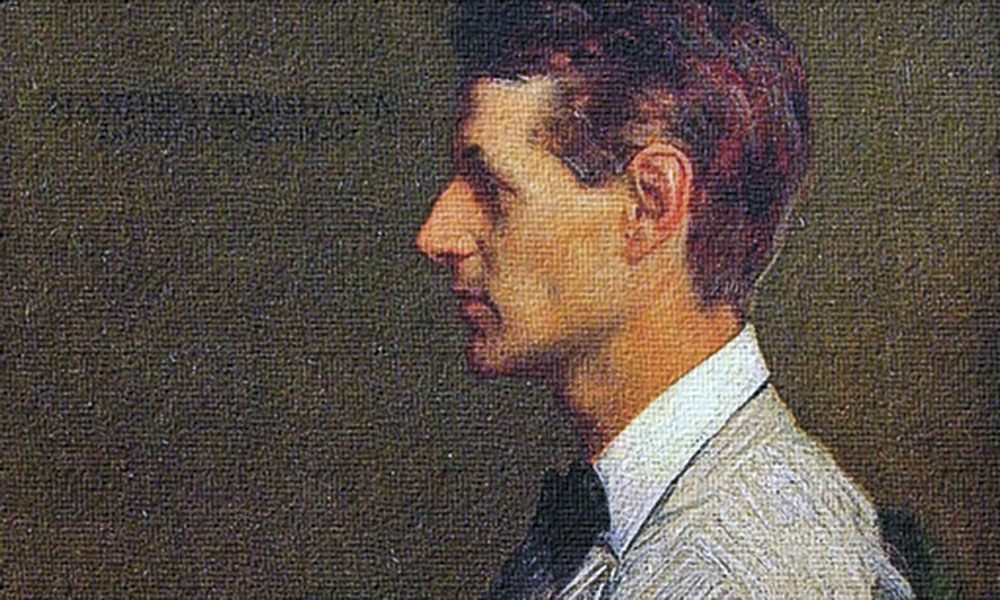

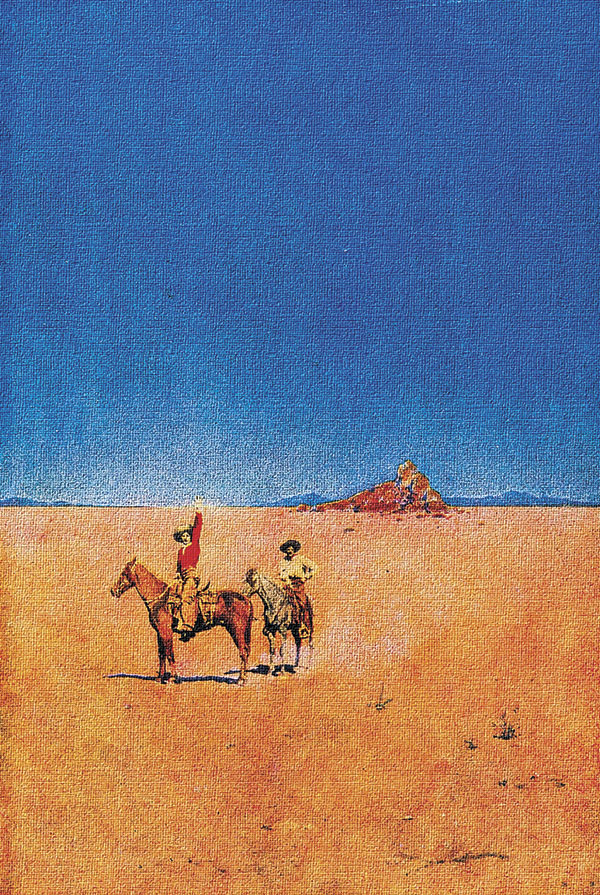

Maxfield, along with his wife, Lydia, visited the resort in the winter of 1901-1902. The artist had contracted tuberculosis in his home state of Pennsylvania and, after a season in Saratoga Springs, New York, he still bore the effects of the pulmonary disease. Hence, he was elated to accept a commission from The Century Magazine that sent him to Arizona Territory to illustrate a series of articles by Ray Stannard Baker titled, “The Great Southwest.” Maxfield created 19 paintings while at Castle Creek Hot Springs.

In a letter published in The Century Magazine, Maxfield detailed his impressions of the Southwest, noting that it had its own local color, different from his home in the Northeast. Describing the landscape in pictorial terms, he compared the formal effects of the desert’s palette to the techniques of the artist Titian.

Remarking on the intense color of the sky—“a blue from dreamland, a blue from which all of the skies of the world were made”—Maxfield added, the “more you look, the more unreal it grows,” a comment that could just as readily be made about the artist’s later iconic landscapes, many of which included crenellated cliffs similar to those at the springs.

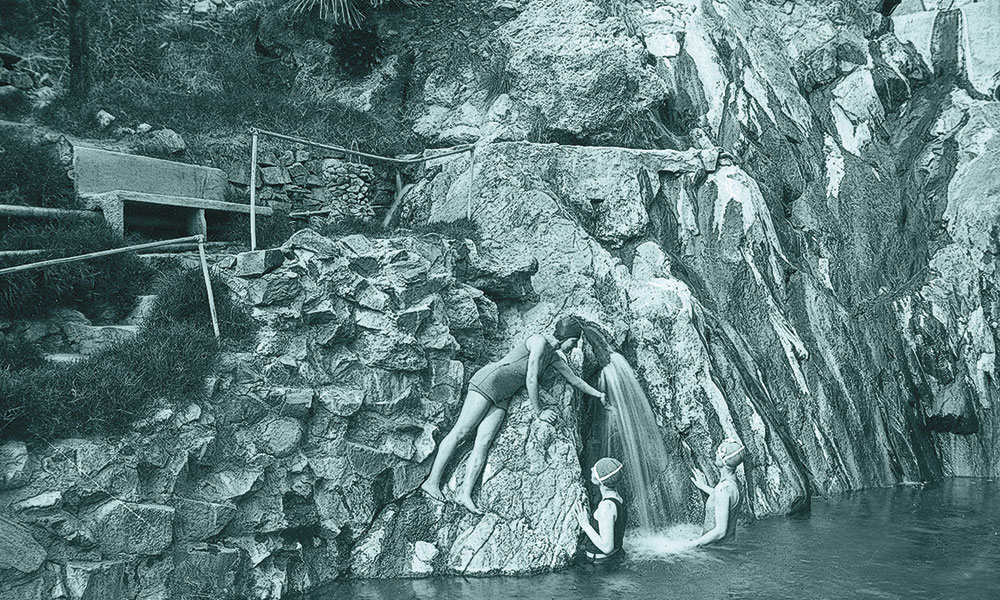

By 1905, the resort, renamed Castle Hot Springs, no longer accepted “patients” like Maxfield. Instead, it became a winter season retreat and added horseback riding as well as tennis and golf to its amenities. Talented professionals were hired to manage and update the resort, setting a standard that would be followed decades later by Arizona resorts such as Arizona Biltmore Hotel and Camelback Inn.

The crew replaced the horse-drawn stage line from the railroad with a motorized service. Along with hotel updates, the new construction included bathing pools, bath houses and bungalows scattered along a well-manicured landscape

— Courtesy Castle Hot Springs —

Pools of History

A veritable verdant oasis in the Sonoran Desert, the hot springs gushed hundreds of thousands of gallons of water a day at a temperature that was barely tolerable to the touch. The water flowed into a series of shallow pools and was used in the resort’s swimming pool and baths.

Attracted to Castle Hot Springs, the resort’s clientele became primarily a who’s who of established industrialists and magnates from the Midwest and East Coast. It survived the early 20th-century recessions, the Great Depression and even served the military as a “rest center” during WWII, when one guest included then-future president John F. Kennedy. After Pullman travel went out of fashion, patrons could fly into Phoenix Sky Harbor Airport and take a chartered helicopter to the resort.

— Cox Portrait Courtesy National Academy Museum, New York City —

Castle Hot Springs continued to operate until 1976, when the main hotel building burned down. Arizona State University operated it for a few years as a conference facility—promoting the Col. Craig version of its history—but found it unprofitable and sold it in 1987. A series of owners unsuccessfully tried to reopen the resort.

— Parrish Painting Courtesy Heritage Auctions, November 24, 2013 —

Closed for more than 40 years, Castle Hot Springs will open for business this fall. Arizona’s oldest resort is being restored by a long-time Phoenix philanthropist and his wife who, along with Westroc Hospitality, are committed to bringing Castle Hot Springs back to its original grandeur.

A historian and cultural resource advocate, Vince Murray is an Arizona native from a pioneer family. He has a master’s degree in Public History from Arizona State University. The president of the Coordinating Committee for History in Arizona, he owns Arizona Historical Research, a consulting firm in Phoenix.

https://truewestmagazine.com/hot-springs-south-dakota/