— Courtesy Bill O’Neal and Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, the University of Texas at Austin, Walter Webb Papers, di_11083 —

When does a boy become a man? The age-old question regenerates itself when a proud, but tired, young mother places a gentle kiss on the cheek of her wailing newborn son and prays silently that life will treat him kindly. She envisions her baby will grow into a virile young man, just as handsome as his father.

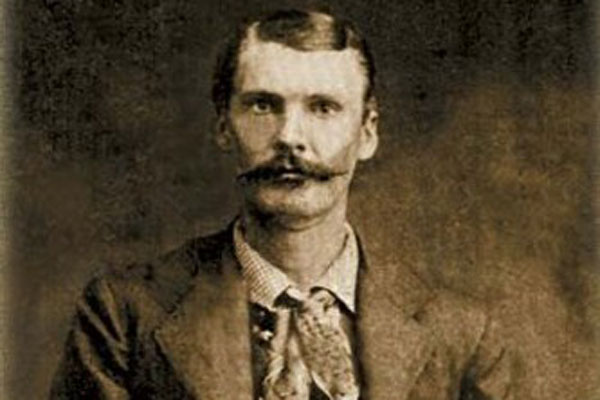

For John Calhoun Pinkney Higgins, nicknamed Pink, manhood came quickly, much too quickly, on the dangerous, but exciting, Texas frontier.

By the time Pink turned 26, a series of events leading to his participation in the Horrell-Higgins feud would cement his reputation as a deadly gunslinger.

Dying Young

Pink entered this world on March 28, 1851, in Macon, Georgia, as the first son, but third child, of John Holcomb and Hester West Higgins. Three years later, the Higgins family departed for Texas, a relatively new state, as the U.S. had annexed the Republic of Texas into statehood in 1845. The Texas frontier would brand Pink a gunslinger by necessity.

The Higgins family traveled by wagon train to Austin before putting down roots 70 miles northwest in Lampasas County in 1857. The family ranch, Higgins Gap, is now called Izoro, reports Texas State Historian Bill O’Neal, whose Great-Grandfather Jess Standard worked with Pink on the 1870s-80s cattle drives. O’Neal’s extensive research informs much of what historians know about Pink.

A teenaged Pink protected his mother and siblings during frequent livestock thefts and Comanche attacks on the open range during the Civil War, while his father performed field duties as a private in the Second Regiment of the 27th Brigade, Texas State Troops.

Pink learned early to deal harshly with thieves. Two heartbreaking massacres of local Lampasas boys emphasized the ever-present danger Pink felt.

On April 10, 1862, James Gracy, 15, was gathering his family’s horses about nine miles west of town. He was joined by a younger boy, John H. Stockman, who lived to tell the horrific details of Gracy’s fate, as recounted by Stockman’s family:

“Stockman was trying to kill a turkey a short distance from Gracy, and in a body of post oaks, he heard a rumbling sound—then shouts, and, on looking, discovered 15 Indians in charge of about a hundred stolen and frightened horses.

“Checking up the herd, three of the savages seized little Gracy, stripped off his clothing, scalped his [sic] as he stood upon the ground, then beckoned him to run, and as he did so, sent several arrows through his body, causing instant death.”

— Courtesy DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University, Lawrence T. Jones III Texas Photography Collection —

Stockman survived by quickly shedding his white shirt to make himself less visible. He then lay silently in a ravine. But another danger immediately arose.

An additional companion had tagged along, a creature often characterized as a “man’s best friend.” Stockman was forced to choke his own dog to death, to keep it from giving away his position, a family descendant wrote.

His friend tortured to death and his dog killed by his own hand, Stockman somehow gathered enough strength to escape. His family reported that “he crawled perhaps half a mile, lacerating his flesh and limbs, and while so engaged, a part of the Indians in preventing a stampede of the horses, rode past without seeing him in the high grass.”

Stockman then ran several miles to safety at Thomas Espy’s place.

Six years later, on January 30, another 15 year old was killed by Indians, Prince L. Ryan, who had been searching for his family’s wandering cow near Lampasas. The Ryans buried their son at Cook’s Cemetery, the oldest in Lampasas, where only a few headstones today remain visible.

Enmity of a Dangerous Man

After the Civil War ended, too many outlaws stole livestock on the Texas frontier. Not yet enclosed by barbed wire, the open range allowed for expedient thefts and fast getaways.

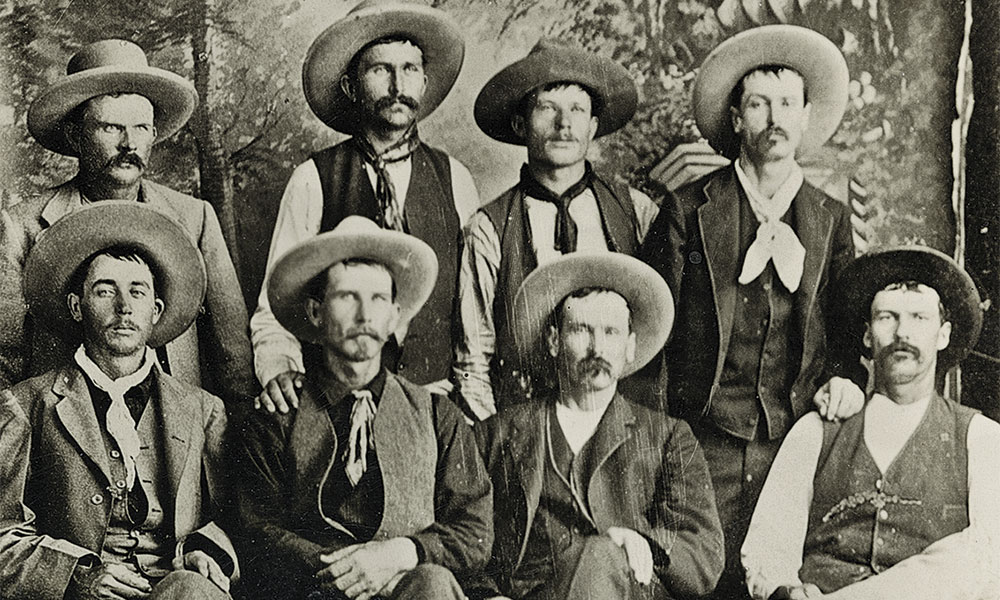

Pink became a member of the Law and Order League that lynched these rustlers. Pink and the crew rode swift horses, changing mounts when needed, to pursue and execute the outlaws.

At the age of 18, Higgins personally hanged a horse thief. “Rustlers who posed a personal threat to Pink and his property would find that they had incurred the enmity of a dangerous man,” reported O’Neal, in his Pink biography.

Cattle theft initiated the notorious Horrell-Higgins feud. Pink achieved local, but prominent, notoriety in 1877 as the leader of the Higgins faction. Pink’s smoldering animosity toward Merritt Horrell became volatile and would result in a fatal confrontation between the two men in the Gem Saloon on January 22.

Pink had grown up with the Horrell boys—Merritt, Tom and Mart—and herded cows with them. Then they began to “go wrong,” Pink told Clifford B. Jones, manager of the Spur Ranch, from 1913 to 1939, where Pink worked as a stock detective during his later years.

“They [Horrell boys] would steal a bunch of cattle; forge a bill of sale,” Jones wrote. “They did this [against] Higgins several times and he finally sent them word ‘that they had bill of saled’ the last bunch of his cattle; that if they ever stole another animal from him that he would get them.”

Following a deadly gunfight in Lampasas in 1873 that left four lawmen dead and wounded Mart and Tom, the Horrell brothers went on a killing spree in Lincoln County, New Mexico Territory. Word of their violence must have followed them back to Lampasas, Texas, when they returned in 1874, but Pink wasn’t fazed—even after the brothers went to trial for the Lampasas killings, but ended up acquitted.

— Courtesy DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University, Lawrence T. Jones III Texas Photography Collection —

Shortly after, in April 1876, Pink found one of his cows in a herd departing Lampasas County. The herd’s owner said Merritt had sold him the cow. Pink took the matter to court in Lampasas, but authorities released Merritt after examining his copy of the bill of sale for the cow.

“After they left the court Pink told Merrit [sic] that if he ever stole any other cow of his he sure would kill him,” wrote William R. Wren, one of Pink’s allies and a witness to the feud, in a letter to the Rev. L.R. Millican, who counseled the Horrell brothers, written several decades after the Horrell-Higgins dispute ended.

Trouble developed on January 20, 1877. “Jim Cooksey was leaving the county with cattle and Pink was looking it over and found a cow of his and Jim showed him [Pink] a bill of sale to the cow from Merrit [sic] Horrell,” Wren wrote.

Two days later, Pink and some pals tracked down Merritt. Finding him sitting near the fireplace with a man named Saunders at the back of Jerry Scott’s saloon, Pink said, “‘Mr. Horrell, this is to settle some cow business,’” and then aimed his Winchester rifle and “shot Merrit [sic] in the front and killed him and not in the back,” Wren wrote.

“Merritt had on his person concealed a six shooter and bowlegged Saunders swore at Pink’s trial Merritt made an effort to draw his guns but Pink got him too quick.”

Gunning for the Horrells

The Horrell-Higgins feud escalated, heightened by deadly skirmishes and ambushes. The feud reached its peak on June 7, when a gunfight between the two factions exploded in downtown Lampasas. Pink’s wife lost her cousin, Frank Mitchell, to the bullets, while Pink’s friend Wren was wounded. On the Horrell side, newcomer gang member Jim Buck Miller was killed.

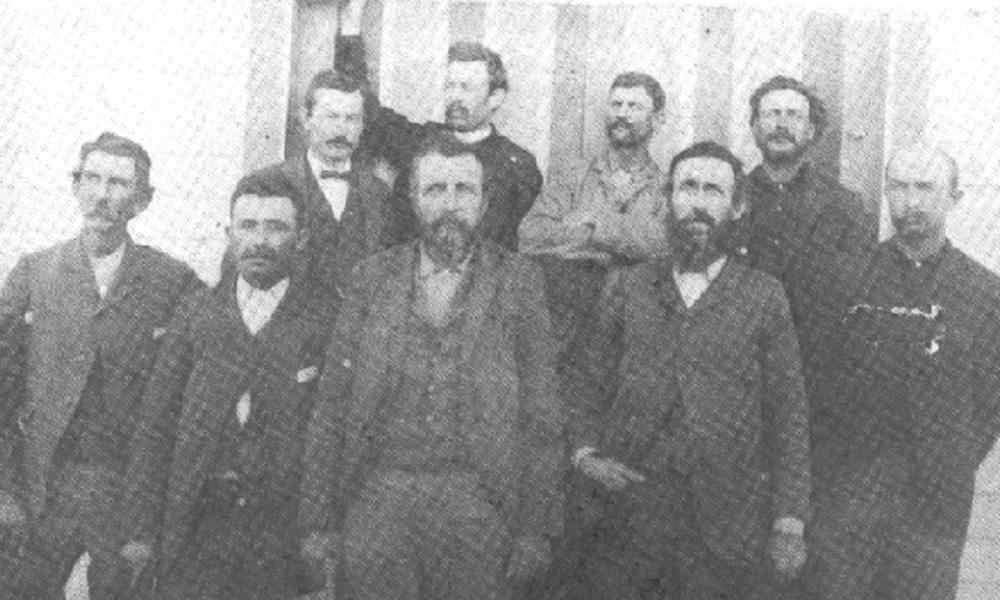

To help control the violence, Sheriff Albertus Sweet sent for the Texas Rangers. On June 14, Maj. John B. Jones arrived with his men and set up camp along Hancock Springs.

Jones helped the two factions craft letters that served as a peace treaty. Tom, Sam and Mart Horrell signed their declaration of peace on July 30, whereas Pink Higgins, Bob Mitchell and Bill Wren signed theirs on August 2.

— Courtesy DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University, Lawrence T. Jones III Texas Photography Collection —

The gunsmoke dissipated. The blood dried. The verdict for Merritt’s murder wouldn’t come until more than a year later. On September 27, 1878, a Lampasas court declared Pink not guilty.

Some historians claim the Horrell-Higgins feud ended not at the time of the treaty, but on December 15, when Mart and Tom were killed while in a Meridian jail.

Arrested as accomplices in the killing and robbing of J.F. Vaughn, a shopkeeper who kept large quantities of cash in his store in Bosque County, Mart and Tom had been no match for the mob that broke into their jail cell and shot them dead.

The last living Horrell brother, Sam, moved his family to another Texas county and then out of the state.

Pink continued to rely upon his firearm during additional confrontations throughout his life, yet no one killed him during a shoot-out. The 62 year old fell dead from a heart attack in his home at Catfish Creek near Spur, in Dickens County, on December 18, 1913.

Pink had used his Winchester so often that the rifle became an extension of him. He frequently shot from his hip, placing his thumb on the trigger, allowing for rapid fire that surprised his victims. He relied on his determination, boldness, wits and his Winchester to survive. Another Spur Ranch manager, Charles Adams Jones, wrote of Pink: “In view of the time and the circumstances, one must not be too quick to condemn him: it was either kill or be killed.”

Kenyon Bennett is the daughter of a cattle rancher in Lampasas County, Texas. One of her sisters lived at the Lampasas home of Pink Higgins’s grandson, attorney John Tom Higgins. Bennett interviewed the Higgins family for this article. She highly recommends Bill O’Neal’s excellent books The Bloody Legacy of Pink Higgins and Lampasas, 1855-1895.