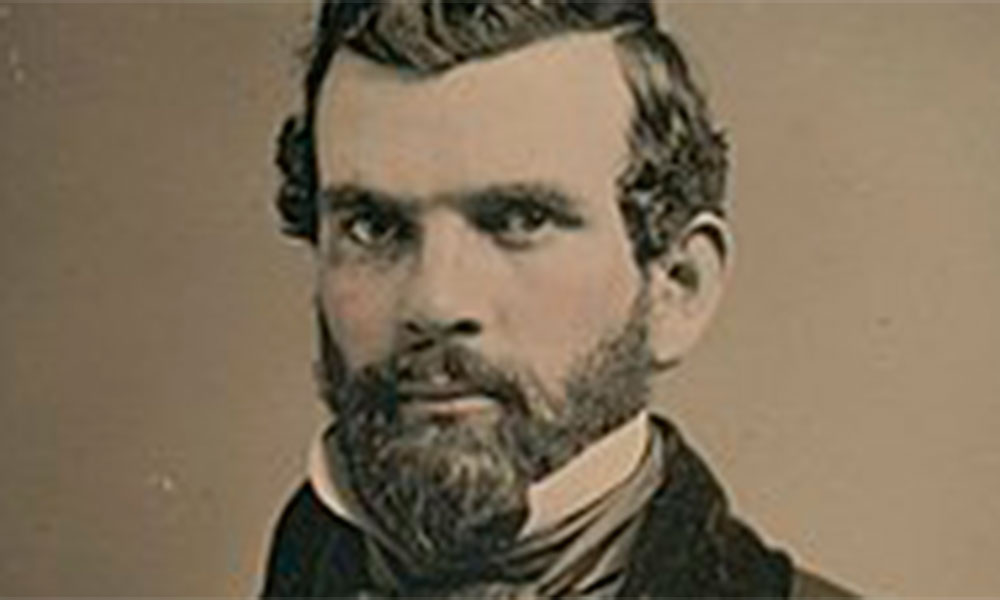

— Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection —

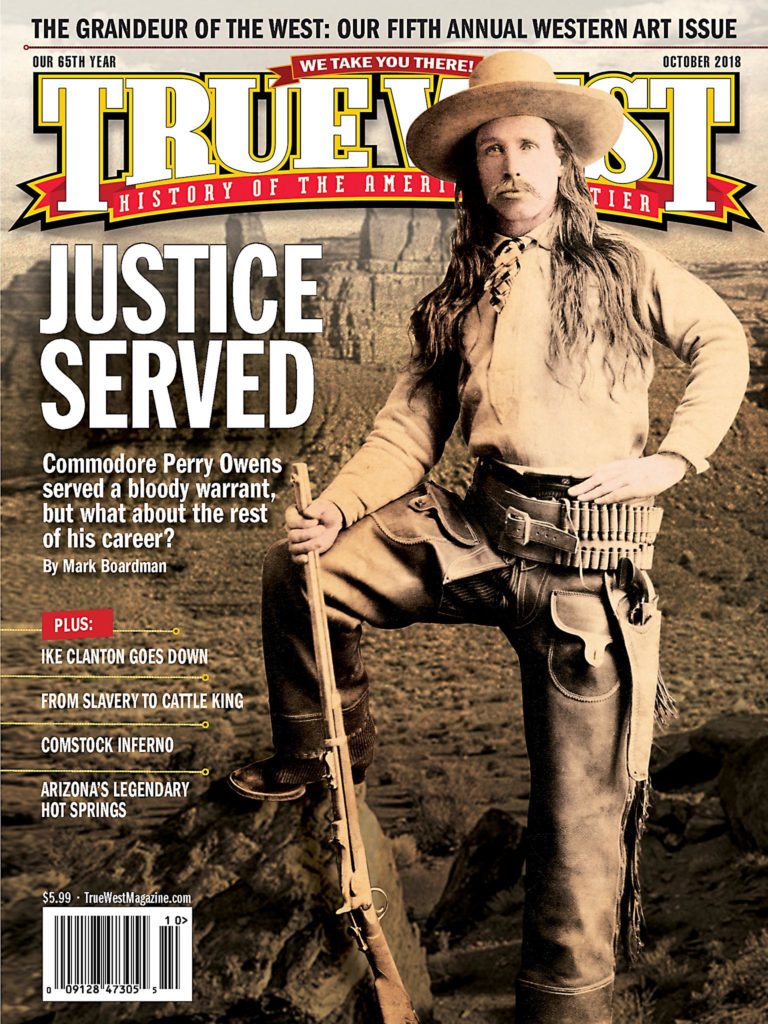

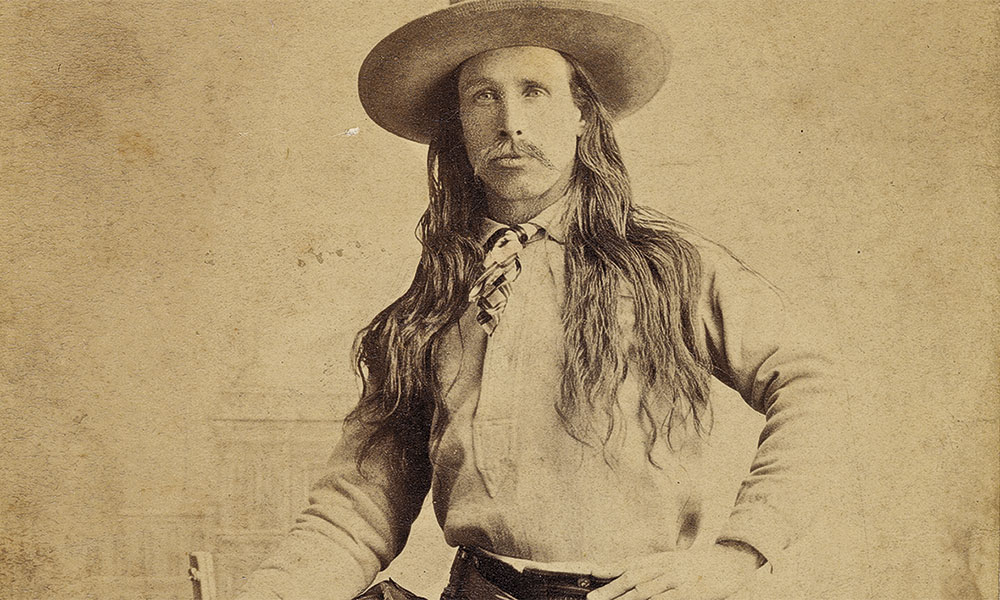

Commodore Perry Owens. One of the most unusual names in the Old West; maybe one of the coolest. And that iconic photo of him—the stylish Westerner, Wild Bill-style long hair and armed to the teeth. He even came out the winner in a classic gunfight, putting three notches on his gun. Commodore seems to be the epitome of the legendary sheriff.

But a closer look shows a guy who was an average lawman at best—who benefitted from that name, that photo and the one instance of blazing glory.

— All images True West Archives unless otherwise noted —

The Peaceful, Deadly Quaker

Owens had an average start, born in Tennessee on July 29, 1851, and growing up in Indiana (as a peaceful Quaker, no less). His mother was a history buff; she named him after the War of 1812 naval hero. He left home at about 13, and that’s where his story get cloudy. The next record of the man appears in 1877, when “Hanging Judge” Isaac Parker found him guilty of running whiskey in Indian Territory.

After that, he spent a brief period in New Mexico Territory—highlighted by the famous photo of him, featuring a long-haired man in fine Western duds and a broad-brimmed hat, armed with a rifle and pistol in what appears to be a buscadero rig. By the time Owens became a lawman seven years later, the hair was cut and the clothing was more conservative.

By 1881, Owens was in Apache County, Arizona Territory, serving as a cowboy and stock detective. During this period, he built a reputation as a dangerous man. He was a crack shot with rifle and pistols. Stories said that he killed several rustlers (he later claimed he sent 14 men to their dooms). No proof supports that, except in one case.

In 1883, Owens shot and killed a Navajo youngster. Owens claimed the victim and two pals had been rustling cows. The two friends denied it and said Owens just opened fire without warning. Owens was arrested, but never tried; the death of an Indian wasn’t considered a terribly criminal act by Apache County officials.

Owens had supporters, men of power and prestige who could always find a role for a man with his talents, real or imagined. In 1886, friends convinced him to run for sheriff of Apache County on the Peoples’ Party ticket. The Apache County Stock Growers’ Association threw its power behind him, which included endorsements by both local newspapers. It was a close election, but Owens won 500 to 409.

He took office on January 1, 1887, and immediately set out to serve standing warrants on various miscreants—many of whom were outside the jurisdiction. He was on the road for most of the first two months in the job, a pattern he would repeat throughout his tenure, and one that folks would increasingly criticize.

The trek led to more stories. Owens came back with no prisoners, and rumors claimed he’d served a permanent justice by killing several of them. That was never proven. For his part, Owens didn’t comment. Still, criminals were on notice, and Owens’ benefactors in the stock growers group were pleased. Initially.

Commodore Comes Up Short

But the man had limits, some not his own.

Three men, including a constable, were killed at the nearby Navajo reservation on February 5. Owens wanted to arrest the perpetrators, but he had no jurisdiction on the reservation. The alleged killers went free, and to some, Owens appeared weak. The criticism started up.

On March 29, four prisoners broke jail in Holbrook. Owens blamed his friend and deputy Joe McKinney and fired him. McKinney was well-respected and folks believed he was scapegoated. Owens later apologized to him, but the damage was done.

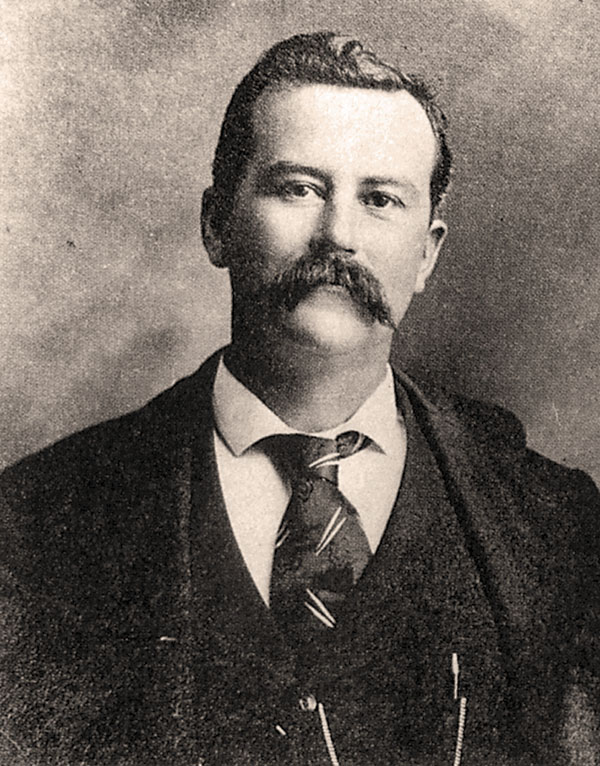

McKinney wasn’t the only deputy to leave. Jeff Milton—already well-known in the Southwest—spent only a couple of days on the job before quitting, saying he couldn’t get along with the sheriff. A number of deputies either left or were fired. The sheriff dumped a fair amount of his paperwork on the deputies, and they resented it. Owens may or may not have been a hard case and shootist, but he was definitely not a people person. Even with his bosses.

As 1887 flew by, stock growers began getting more and more disenchanted with their lawman. Crime, especially rustling, was still rampant. Owens was frequently out of the office and unavailable.

The ranchers thought they were getting a stone-cold killer who would take the law into his own hands. They got a man who wanted to do things up front and legal…and slow. His bosses were impatient, Owens biographer David Grasse states.

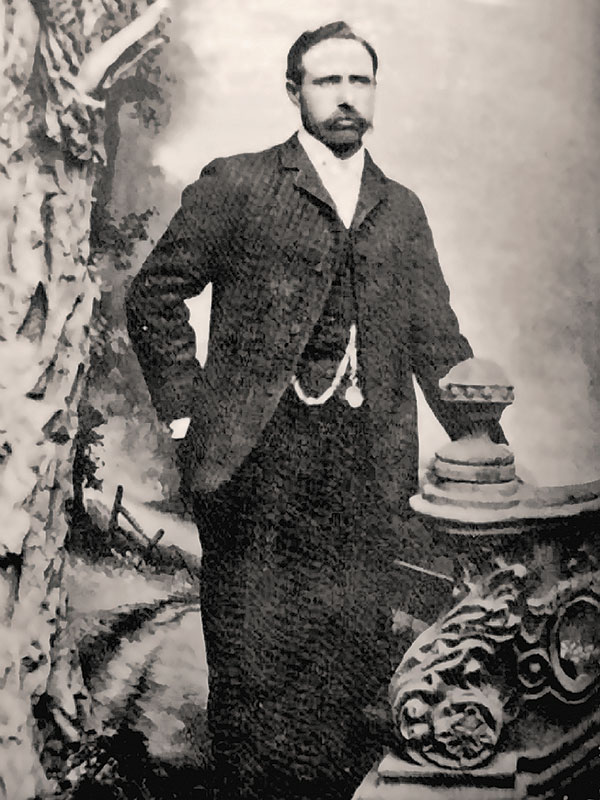

The association hired a stock detective, Jonas “Rawhide Jake” Brighton. Brighton also had a reputation as a killer—and he proceeded to back it up.

On June 1, Brighton shot and killed famed outlaw Ike Clanton, who’d been rustling cattle throughout the region. A month later, Brighton killed Clanton associate Lee Renfro, and stories circulated that Brighton murdered several other criminals. In some of those cases, Brighton rode with Apache County deputies, giving his actions a certain legitimacy.

Owens was out of the area, serving warrants, perhaps staying away from some bad situations.

The Blevins Fight

The heat was on Owens to prove his worth, which may be why he decided to arrest Andy Blevins, alias Andy Cooper.

Blevins was a major player in the Pleasant Valley War, which was tearing apart nearby Yavapai County. But he and his family were also rustling cows and horses in Apache County. His arrest warrant had been issued a year earlier, in 1886, before Owens took office. Owens decided to enforce it on September 4.

The situation was strange. Owens decided to arrest Blevins on his own, even though help was offered and perhaps needed. He didn’t check out the scene before marching to the Blevins family cottage in Holbrook, Owens’ home base; if he had, he would have discovered 11 people in the 600-square-foot house—seven of them women and children.

Despite the red flags, Owens went ahead.

In the gunfight that followed, Owens killed three men (Andy, his 15-year-old brother, Samuel, and family friend Mose Roberts) and wounded another (Andy’s half-brother John), in under two minutes. The Blevins side got off just one shot.

Critics accused the sheriff of giving the family no chance. Owens got national attention, and the incident made him a legend. It was the high point of his career.

After the Gunfire

In the coming months, four more prisoners escaped Owens’ custody. He spent even more time away from Holbrook.

The St. Johns Herald got more and more critical: “…his visits are like the ‘second’ coming for verily, no man knoweth whence he cometh, or whither he goeth.”

Owens couldn’t find sureties to put up the bond required for office holders; in fact, over two years in office, 23 people came and went as bondsmen. Most of them were stock growers members or friends—another indication that he was losing key support.

In August 1888, Owens announced he’d seek reelection; he couldn’t even garner his party’s nomination. He would run for the office twice more and lose—although he occasionally served as a deputy, and, in 1892, he was appointed a deputy U.S. marshal.

Owens did get a top job again, in 1895. The western part of Apache County was carved off and made Navajo County; Owens was named sheriff. But his law aptitude didn’t change. Owens fired two deputies in the first year in office. A prisoner escaped from the Holbrook jail under his watch. And some locals resented that Owens was often on the road.

Maybe the lawman didn’t need the hassle; he didn’t run for reelection in 1896. His law enforcement career was over.

The rest of his life was not exactly the stuff of legend. He moved west to the town of Seligman in 1898, working a variety of jobs. He set up a saloon (nicknamed “Bucket of Blood”) and a grocery just off of his house. In 1910, Owens moved to San Diego County, California, and ran a farm. It must not have worked out, for he was back in Seligman the next year.

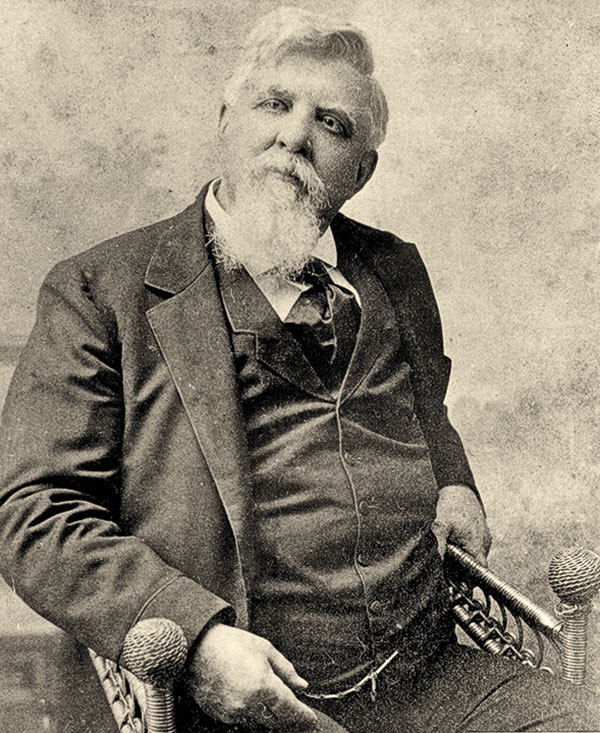

Family took up the ex-lawman’s time. His chief deputy during the Navajo County tenure was his nephew, Bob Hufford. Owens made at least a couple of trips to Indiana to see his siblings and their children. And in 1901, the 50-year-old confirmed bachelor took a big leap: he married Elizabeth Jane Barrett, 22. They would have no children.

Perry’s later life was unremarkable, but he wasn’t exactly forgotten. Between 1897 and his death in 1919, Owens was the subject of several articles that loved his name, lauded his gunhandling and pushed forward the myth of the long-haired lawman who killed three desperate men in 1887. When he died of dementia and kidney disease on May 10, 1919, those tales were still being told, far and wide.

When the legend becomes fact, print the legend indeed.

A Classic Gunfight: September 4, 1887

Apache County Sheriff Commodore Perry Owens stepped onto the porch of the Blevins home in Holbrook, Arizona Territory, and knocked on the west-facing door. The Apache County sheriff was there to serve a warrant on Andy Cooper, a horse thief.

The door opened slightly, and Andy Blevins, alias Andy Cooper, peered out. The sheriff immediately spotted an ivory-handled pistol in the outlaw’s hand.

“Andy,” Owens said, “I have a warrant for you. Let’s have no trouble.”

“Give me a few minutes, I’m not ready yet,” Andy replied, as he tried to close the door, but Owens thwarted the maneuver by pushing his boot into the narrow opening.

Ducking behind the door, Andy brought his six-shooter up to fire. Without removing the Winchester from the crook of his arm, Owens fired blindly through the door. His lucky shot hit Cooper in the stomach.

As he backed up, the sheriff levered his Winchester, ejecting the spent shell and slamming another into the breech. He quickly covered all the windows and doors in anticipation of other assailants.

A woman screamed. Before Owens could react, a second door opened slightly and the barrel of a six-shooter protruded and fired about four feet from the lawman. The bullet just missed Owens and instead hit a horse tied to a cottonwood tree in front of the house. The terrified horse broke its reins, ran a short ways and then toppled dead in the street.

Andy’s half-brother John attempted to take cover behind a door, but Owens fired another intuitive shot, hitting John in the shoulder and sending him crashing to the floor.

Owens scanned the house through his rifle sights, watching for an attack from any and all corners. He heard a noise, which he recognized as a window being opened.

Owens ran from the front door to the front window, where he saw Andy on his knees, about to get a shot off through the narrow slit. The sheriff fired, and the bullet tore through the thin board siding, hitting an already wounded Andy in the right hip.

So far, the sheriff’s three shots at invisible targets produced three direct hits.

As Owens levered another cartridge into his rifle, he heard a woman pleading with someone inside the house. After a commotio and more pleading, the front door opened.

Fifteen-year-old Samuel Houston Blevins boldly stepped out, brandishing Cooper’s pearl-handled pistol and vowing to “get” the sheriff. Owens’s fifth shot hit the boy squarely in the chest. The lad dropped dead on the doorstep.

His every sense on high alert, Owens stood alone in front of the house, waiting and listening. He had no idea how many more men were in the house. His keen ears caught a noise on the eastern side. He ran to the corner of the house, catching Blevins family friend Mose Roberts as he climbed out a window with a pistol in his hand. Owens fired, hitting Roberts in the chest.

The sheriff chambered another cartridge. By now, the screams and wails inside the house were dreadful. After a few anxious minutes, Owens realized no one else would be coming out to fight.

Satisfied he had finished his work, the sheriff walked up the street toward the livery stable, where he met several townspeople coming his way. “Have you finished the job?” A.F. Banta asked.

“I think I have,” Sheriff Owens curtly replied.

—By Bob Boze Bell

Mark Boardman is the features editor for True West Magazine as well as the editor of The Tombstone Epitaph. He also serves as pastor for Poplar Grove United Methodist Church in Indiana.

https://truewestmagazine.com/commodore-perry-owens/