— Courtesy ABC —

Six decades ago this September 30, a Western series premiered, starring a ballplayer-turned-actor and a one-season Mouseketeer as father-and-son ranchers in New Mexico. Despite being a black-and-white drama, The Rifleman, distributed by the Peter Rodgers Organization, continues running on cable, Internet platforms and on DVD. Why does it endure?

The answer begins with the creators. Jules Levy, Arthur Gardner and Arnold Laven, who’d met in the Army Air Forces Motion Picture Unit during WWII, were given the chance to create a Western story for Zane Grey Theatre, produced and hosted by Dick Powell.

“Powell used Zane Grey Theatre as a proving ground for pilots,” Gardner recalled.

Seven series, including The Westerner and Wanted: Dead or Alive, had begun on Zane Grey Theatre. The problem was, the trio didn’t have a story, only a title.

Enter an ex-Marine screenwriter who’d learned his craft by adapting nearly a dozen episodes of the CBS radio series Gunsmoke for TV. Sam Peckinpah gave them a script: a skilled marksman enters a shooting contest, but the town powers have bet on someone else. They let him know that if he wins, he’ll die. He throws the match: the end.

The trio hated it—this guy was a coward, at least by Western standards.

Then Laven asked, what if he has a son, and the son will be killed if he doesn’t lose the match?

That premise, the studio loved. Lucas McCain became an unusually realistic hero for the genre: powerful, wise, independent. But even he couldn’t always triumph when the cards were stacked against him, although, in the long run, good won out over evil.

— Crawford photo courtesy One-Eyed Horse ProductionS —

Peckinpah, who grew up on his family’s ranch in Fresno, California, based the father-son relationship between Lucas and Mark McCain on his relationship with his own father.

Casting was crucial. Chuck Connors, six-foot-five and lantern-jawed, was a Brooklyn-born natural athlete. After the U.S. Army, he played basketball for the Boston Celtics, then switched to baseball, playing for the Brooklyn Dodgers, then for a Chicago Cubs farm team in Los Angeles. There, he was given a small role in 1952’s Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn comedy Pat and Mike.

“They paid me $500 for my week’s work in that movie,” he recalled. “Baseball, I told myself, just lost a first baseman.”

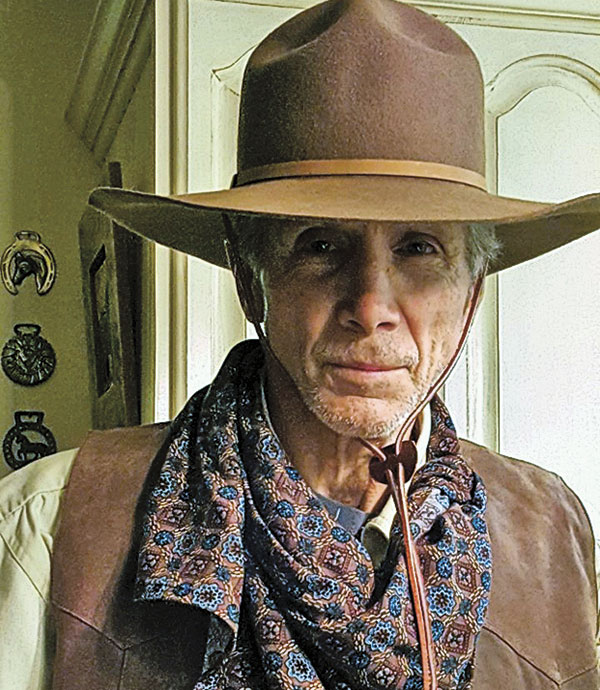

Johnny Crawford, a busy actor from age four, had appeared in more than 30 movies and TV shows by the time he auditioned for The Rifleman.

Obsessed with silent Westerns, “I was a fan most of William S. Hart,” he tells True West. “I remember my audition vividly. I’d gotten several Western episodes, and I hadn’t been so convincing as a cowboy. My mother, who was an actress, gave me lessons in cowboy talk.”

Johnny auditioned for the partners, then for Connors. “I didn’t see him right away, because he was only 12 feet tall,” he recalls with a laugh.

That tall cowboy, Connors, remembered: “We must have interviewed 20 or 30, then Johnny came in and before we even talked to him I said, ‘That’s him. That’s the rifleman’s son.’”

In that first season, unprecedentedly, 13-year-old Johnny was nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Emmy. He lost to Gunsmoke’s Dennis Weaver. The series lost Best Western Series to Maverick and never earned another Emmy nomination, but that may have been their own fault: the producers walked out on the banquet because they were seated so far back, and Connors, though seated in front, went with them.

The plots were a blend of stark violence and family values. “I killed on average two- and-a-half people per show,” Connors recalled. “We had the benefit of the father-son relationship, so I could have a scene at the end where I would explain to Mark, essentially, that sometimes violence is necessary, but it isn’t good.”

Peckinpah wrote six episodes and directed four, before quitting. He wanted an evolving story line, with Mark growing to manhood; the producers wanted to keep Mark a kid.

Johnny’s brother, Laramie star Bob Crawford, guested on The Rifleman and remembers, “They had great relationships with their fathers and sons [Chuck had four sons], and John and Chuck had this extra father-son relationship.”

Because Johnny was a minor, his grandmother was on set every day. “Chuck could be rowdy now and again, but when Grandma was around, Chuck was a pussycat—a Bengal tiger pussy cat,” Bob says.

When The Rifleman found itself opposite the new Lucy Show, it was time to ride into the sunset. Levy-Gardner-Laven would go on to produce many movies, as well as the series The Big Valley.

Connors would have a long acting career in features and TV series, remembered best as the soldier falsely accused of cowardice in the series Branded. He and Johnny would remain close friends until Connors’ death in 1992.

Johnny, who became a genuine cowboy during the making of The Rifleman, would have a rodeo career, an acting career, a stretch in the U.S. Army, a starring role in the Oscar-winning Resurrection of Broncho Billy and a singing career, notably as orchestra leader and singer for the Johnny Crawford Dance Orchestra.

He’s just finished a new movie, Bill Tilghman and the Outlaws, due to be released this October. He stars as his idol, William S. Hart.

Why does The Rifleman series endure? Gardner, who passed away in 2014 at the age 104, summed it up: “It has an eternal theme; father and son. It was a good show. We had five years of good directors and writers and actors. It makes me feel very proud.”

Henry C. Parke is a screenwriter based in Los Angeles, California, who blogs about Western movies, TV, radio and print news: HenrysWesternRoundup.Blogspot.com

https://truewestmagazine.com/johnny-ringo-tombstone/