— Firemen Photo courtesy Special Collections, University of Nevada, Reno Libraries —

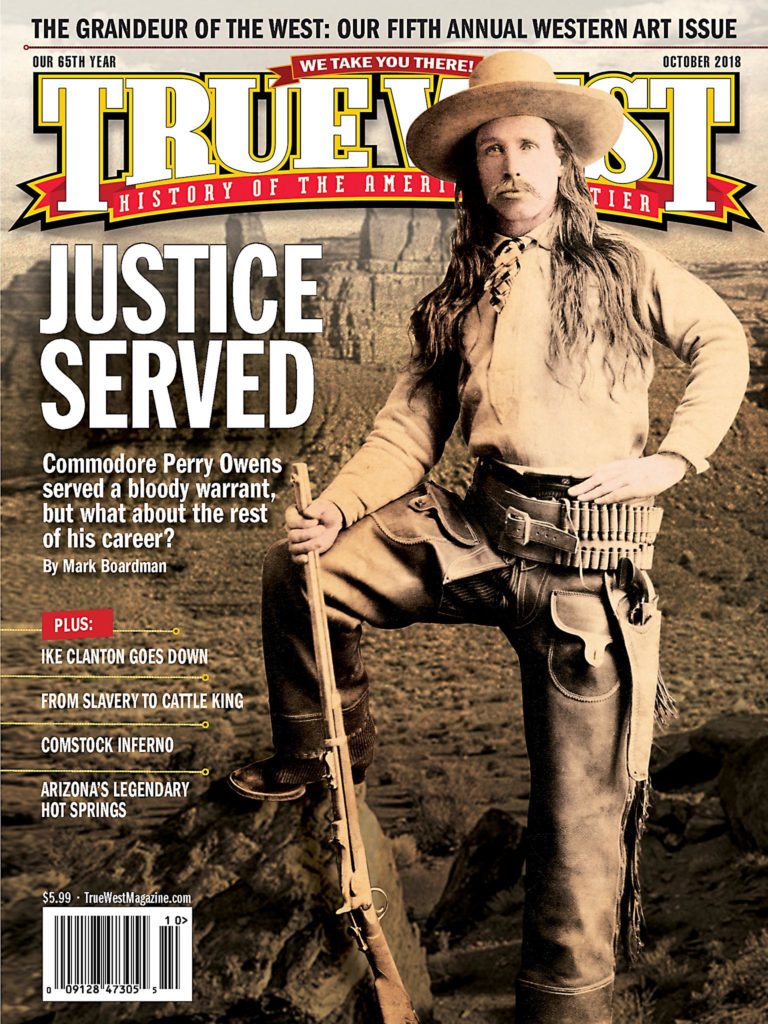

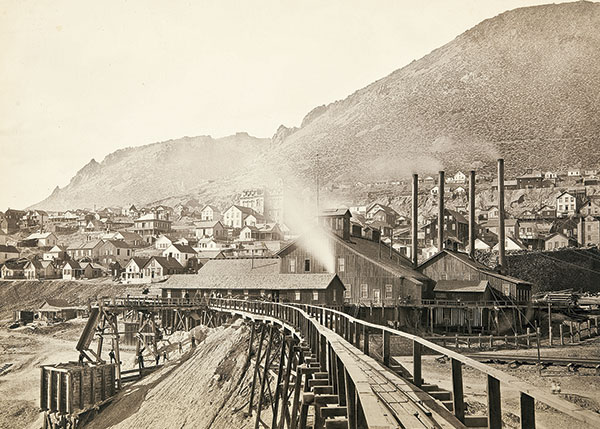

A gray dawn crept into leaden skies over Virginia City, Nevada, on the morning of October 26, 1875. The uniform layer of cloud rushing over the Sierra Nevada Mountains from California portended storm. Fierce winds thundered down the sides of Mount Davidson, churning the dust, thrashing the sagebrush and moaning around the walls of the town.

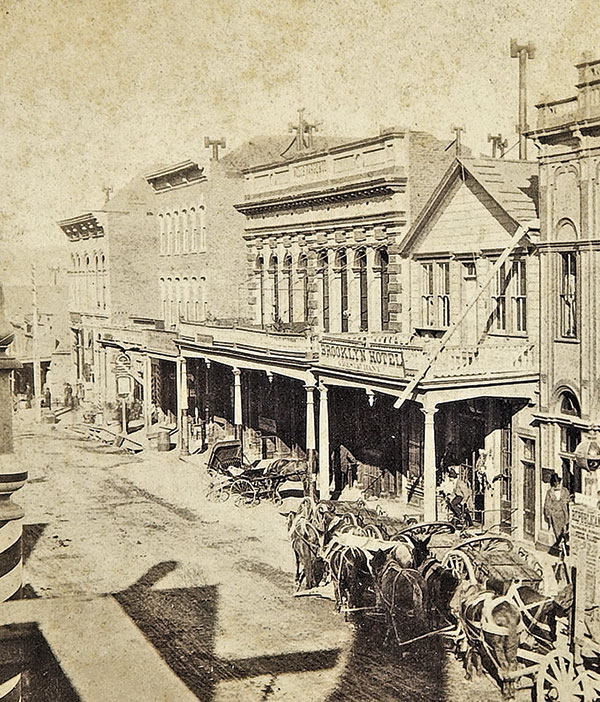

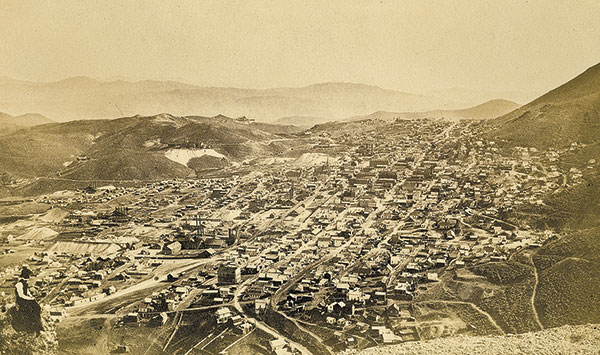

A booming mining community of about 15,000 terraced onto the mountainside built directly over the world-famous Comstock Lode, Virginia City was the dominant settlement in the state and, arguably, the most important between San Francisco, California, and St. Louis, Missouri.

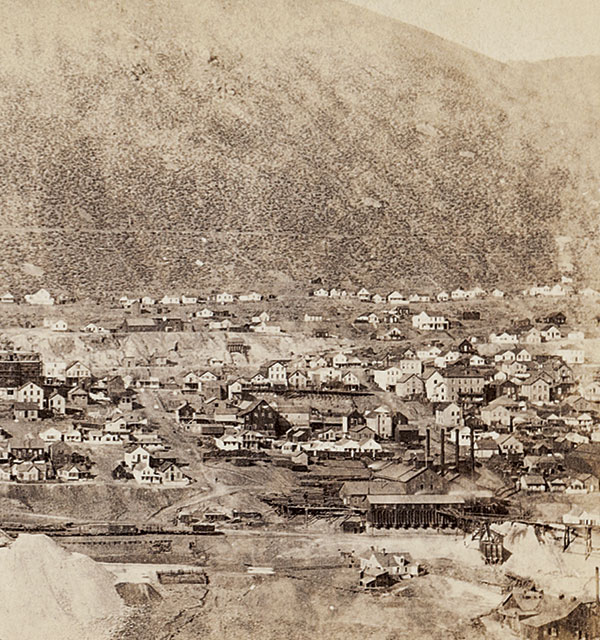

— Courtesy Hearst Mining Collection of Views by C.E. Watkins at UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library —

Staggering quantities of gold and silver had been mined from the Comstock Lode in the 16 years since its discovery—around $200 million worth—making it the Silicon Valley of the age. And the ore body recently struck more than 1,000 feet below the downtown streets in the Consolidated Virginia Mine dwarfed anything previously known. The Con. Virginia’s riches had been revealed only 10 months before, but the mine was already paying more than $1 million of dividends per month.

One of the few persons out that early morning was 10-year-old Grant Smith, scouting for pigeons to shoot with his slingshot. Passing in front of Mooney’s Stable, Smith heard the cry, “Fire!”

— Courtesy Heritage Auctions, December 11-12, 2012 —

The boy looked uphill into the driving wind and saw a thin stream of smoke trailing from a small, one-story frame boarding house belonging to Kate Shay, otherwise known as “Crazy Kate.” People in the adjoining houses had heard a coal-oil lamp break during a drunken fight, one newspaper would later report.

A “garden hose could have put out the fire” at that first alarm, Smith recalled, but scarcely a drop of rain had fallen for months, the town was tinder dry and the fire department arrived tardy.

The firefighters’ efforts went for naught as the angry winds whipped the fire fiend loose. Within 15 minutes, 20 buildings were in flames and church bells were ringing the alarm all over town. In the next five minutes, the number of burning buildings doubled.

A few minutes later, an area equal to a whole city block was aflame. People tumbled into the streets in their bedclothes, many just as their houses caught fire.

Smith rushed home. The pair of two-story houses owned by his family caught fire. His mother salvaged a handful of valuables and hustled him and his three brothers up the hillside to the dump of an old mine.

—Republican photo Courtesy Heritage Auctions, June 13, 2008 —

Acre after acre of buildings joined what one eyewitness described as the “sea of fire.” Desperate to save something from the impending calamity, families three or four blocks ahead of the flames heaped belongings into the streets. Merchants vomited wares onto the sidewalks and fought to engage wagons. Teamsters jacked prices high and urged their animals through the mayhem, cursing.

Frantic citizens pressed every conceivable conveyance into service, from wheelbarrows to barouches. Without time to rig terrified animals into harnesses, men by the hundreds took the place of draft animals and hauled loaded wagons toward the outskirts of town.

Women and children staggered beneath impossible loads. Horsemen galloped through the crowds, heedless of the foot-bound multitudes. Behind them all, the ravening flames leaped and roared skyward.

By 9:00 a.m., a whirlwind of fire enveloped the county buildings, the International Hotel, the Bank of California and the rest of the city’s core above C Street. Twenty-five miles away, the population of Reno could see the black cloud roiling above Virginia City.

— Democratic photo Courtesy Heritage Auctions, May 22, 2010 —

A Race Against Time

Telegrams from Virginia City threw San Francisco into a furor. Much of the city’s fortune rested on the successful working of the Comstock Lode.

The two best mines were the Con. Virginia and the California, both controlled by four Irish partners led by veteran miner John Mackay, who had walked more than 100 miles over the Sierra Nevada Mountains from California to the Comstock a few weeks after its discovery because he was too poor to afford a mule. Mackay took a job in a mine for $4 per day and worked his way up from nothing.

Mackay and James Fair handled the firm’s mining operations on the Comstock; James Flood and William O’Brien, two former saloonkeepers, fronted their interests in San Francisco financial and stock trading circles. Speculators “below,” in San Francisco, pressed Flood for information as a rash of panic selling cratered the market. Flood hadn’t heard from his partners, but he expressed confidence that Mackay and Fair were doing their duty, fighting the fire.

Flood knew his partners well. Mackay hadn’t made the slightest effort to save his own house, which would burn down. He and Fair had been at the hoisting works of the Con. Virginia since the first alarm. Both miners recognized the extreme danger—the Con. Virginia works were in the heart of town, and the wind threatened to drive the fire right over them. They ordered everyone out of their mines.

Anything on the surface could be rebuilt, the whole town if necessary, but if fire burned down the mine shafts and got into the stopes far below, which were held open by an enormous beehive lattice of dry, compressed timbers, they’d lose the richest mine in the world forever.

— Watkins photo Courtesy Heritage Auctions, December 11-12, 2012 —

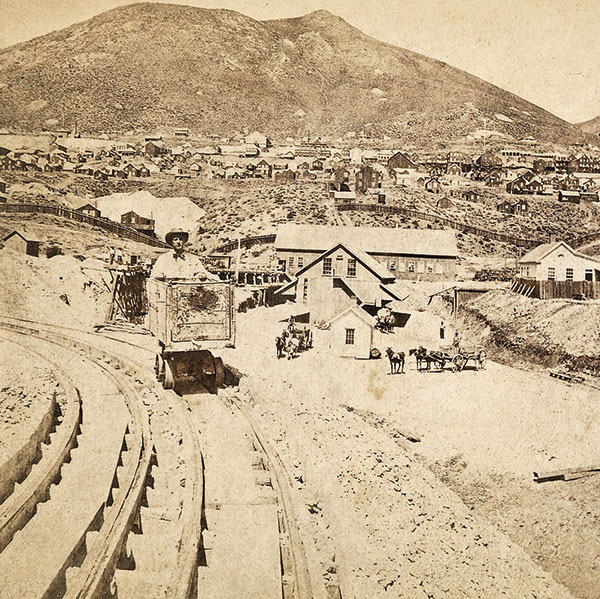

With every last man raised from the mine via cages (elevators raised and lowered by the hoists), Mackay directed his men to seal the mine shaft and pile sandbags, dirt and ore on the bulkhead.

Outside, the fire surged across C Street toward D. If it leaped D Street and caught to Piper’s Opera House on the east side of the street, the whole block between D and E Streets would catch fire. If that happened, nothing could stop the fire leaping E Street, burning the railroad depot and getting level with the Con. Virginia hoisting works. The slightest northward twitch of wind would doom the works.

Mackay led gangs of miners dynamiting the opera house and a line of adjacent houses in the hopes of creating a firebreak. Thudding explosions added a new horror to the mayhem.

A few blocks away, the wood-shingled roof of the Catholic church caught fire. A pious Irishwoman bustled off to find Mackay. “Oh, Mr. Mackay, the church is on fire!” she said. Perhaps he could save it?

“Damn the church!” Mackay exclaimed. “We can build another if we can keep the fire from going down these shafts!”

When the wind began scattering the church’s burning shingles into the city, miners dynamited the entire structure. Wind-driven flames vaulted the firebreaks with hardly a pause. Men fell back before the onrushing walls of flame.

Thousands of feet of mine timbers and hundreds of cords of firewood stored in the depot yard and outside the hoisting works caught fire and swelled to infernos. The volcanic heat melted the metal wheels of railroad cars.

Around 9:30 a.m., flames began to envelop the hoisting works. Driven by wind and the hellish heat, the fire raced down the trestle work supporting the car track over which a mule hauled the ore from the shaft to the mill that separated out the gold and silver. Only when the men heard her terrified braying did they realize that no one had loosed her from her stable.

Getting her out was suicide, but Ben Smith, her devoted groom, secured a pistol and tried to find a vantage from which he could shoot his beloved mule. Desperate to shorten her agony, he wriggled into a crawlspace beneath the hoisting works while the building took fire over his head. Heat scorched his skin and singed his hair and whiskers. The mule’s screams drove him on, but he couldn’t find a vantage point. The mule died in horrible agony. Smith barely escaped with his life.

—Waters photo courtesy Special Collections, University of Nevada, Reno Libraries —

The fire burned along the trestle work and consumed the Con. Virginia’s massive, state-of-the-art mill and the stamp batteries of the California Mine’s almost-complete mill. The battle shifted to the new hoisting works Mackay was having built 1,000 feet farther down the hill over the C&C Shaft, named as a joint effort of the California and Con. Virginia mines.

The C&C works seemed doomed too. With what the Territorial Enterprise described as “his old miner instinct and miner’s knowledge,” Mackay led the desperate fight to save them. Under Mackay’s direction, miners dynamited a line of houses below G Street and dragged away the debris. The San Francisco Chronicle correspondent described the effort as “superhuman.”

The wind was threatening to jump the flames over the firebreak and drive the fire onto the C&C works when a southward swing of the wind gave the men the chance to complete the firebreak. The respite provided the critical opportunity. The fire never crossed H Street, and the C&C hoisting works survived.

By 1:00 p.m., the worst of it was over. The flames died as they ate the fuel that sustained them, leaving ghastly wreckage.

The half-mile-square heart of Virginia City had vanished. Wraiths of smoke coiled above the charcoal and ashes. Here and there stood remnants of brick walls. The great machinery of the mines and mills stood like iron specters in the writhing smoke, every massive arm and wheel still.

Burned Out

Early estimates of the number of people rendered homeless ranged from 2,000 to 10,000. The fire swept away 200 businesses, including “all the small houses on D Street,” which the Daily Alta California described as “occupied by a class of population which will be no great loss to the city.”

A storm built over the Sierra Nevada Mountains, as burned-out residents wandered around looking for places to lay their heads. The Third Ward School housed as many as possible, but even with it and other public buildings and assembly halls packed to capacity and every surviving bed in town double- or triple-shotted with refugees, the available space didn’t suffice. Families sought shelter in old mine tunnels and bivouacked in the lee of boulders and behind sagebrush windbreaks. Campfires dotted the hills around town after dark.

Snow began falling at 8:00 p.m. An hour later, the snowflakes turned to light rain. A series of heavy showers rode through the area on the still-blustery wind about 2 a.m. The Comstock passed a miserable night.

Like so much of the city, the Territorial Enterprise had been burned out. The newspaper reappeared, 48 hours after the fire, thanks to a newspaper proprietor who allowed his rival use of his printing presses.

In a brief article titled, “Characteristic,” the Territorial Enterprise described a “haggard” figure emerging from the successful battle to save the C&C hoisting works, “begrimed with dust, powder-smoke, and the smoke of the fire.”

The man was Mackay, looking “like a laborer just ready to drop from exhaustion.”

Mackay sat on a berm and watched the fire burn itself out. An acquaintance approached and said, “Mackay, you’ve lost what would have bought an earldom today.”

“Don’t speak of it,” Mackay said. “It’s not any matter and isn’t worth mentioning.”

He gathered what remained of his strength and said, “Let’s see what we can do toward making these women and babies comfortable.”

Extreme Danger of Fire

Six years earlier, in 1869, the Yellow Jacket fire had flared up underground. Aside from killing nearly 40 men, it permanently prevented access to the productive stopes on the 800-foot levels of the Kentuck and the Crown Point, despite the pay ore remaining in those galleries.

A number of other mine fires raged underground too, ones that didn’t make headlines because they killed only a few people instead of three dozen, but a well-developed mine fire generally ruined that section of the mine forever because it was essentially impossible to extinguish. The fire would smolder for years in the oxygen-starved environment of the mine, even after it was sealed off, and any attempt to reopen the burned section generally re-charged the fire with oxygen and re-ignited the problem.

Everything underground in the Comstock mines was shored with timber. Since electric light hadn’t been invented yet, all the mining was done by the open flames of candles and lanterns. The danger of fire was beyond extreme.

In contrast, the 1875 fire was on the surface, in the town, but if the miners had done nothing to stop that fire, it would have burned the Con. Virginia hoisting works, traveled down the wooden-framed shaft of the Con. Virginia and gotten into the “bonanza stopes”—the colossal galleries that housed the Big Bonanza, which were shored by an enormous lattice of square-set timber frames, a gigantic underground beehive structure built of one-foot by one-foot wooden framing timbers—and the most valuable mine in the world would have been lost.

Adapted from The Bonanza King: John Mackay and the Battle for the Greatest Riches in the American West by Gregory Crouch. Copyright © 2018 by Gregory Crouch. Published by Scribner. Visit SimonAndSchuster.com to purchase the book.

https://truewestmagazine.com/albert-michelson/