— Courtesy Bonhams, October 16, 2013 —

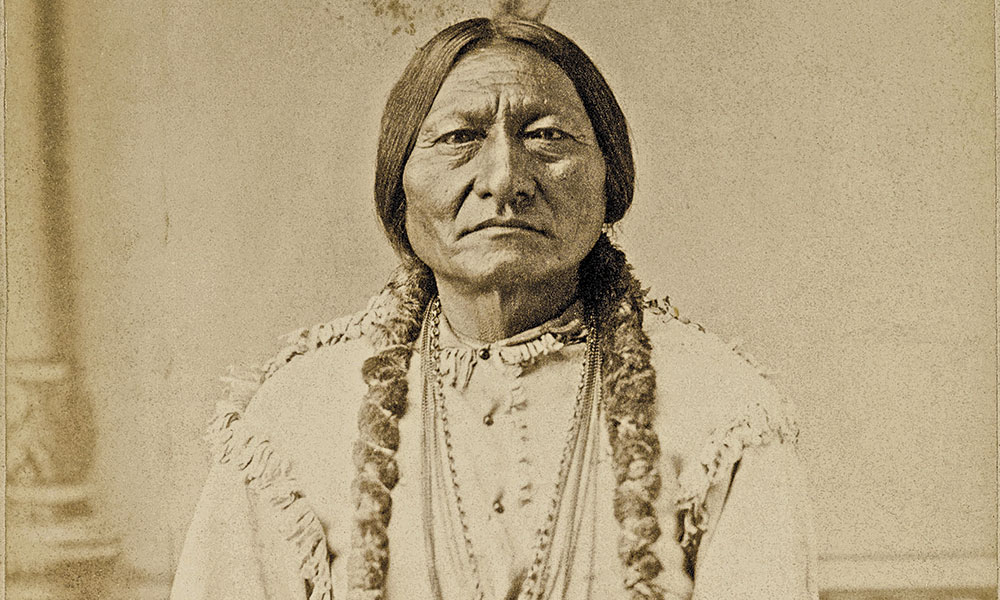

One picture of the famous Hunkpapa Lakota Chief Sitting Bull wearing a crucifix is as iconic as it is enigmatic. History claims missionary Pierre-Jean De Smet gave Sitting Bull the crucifix.

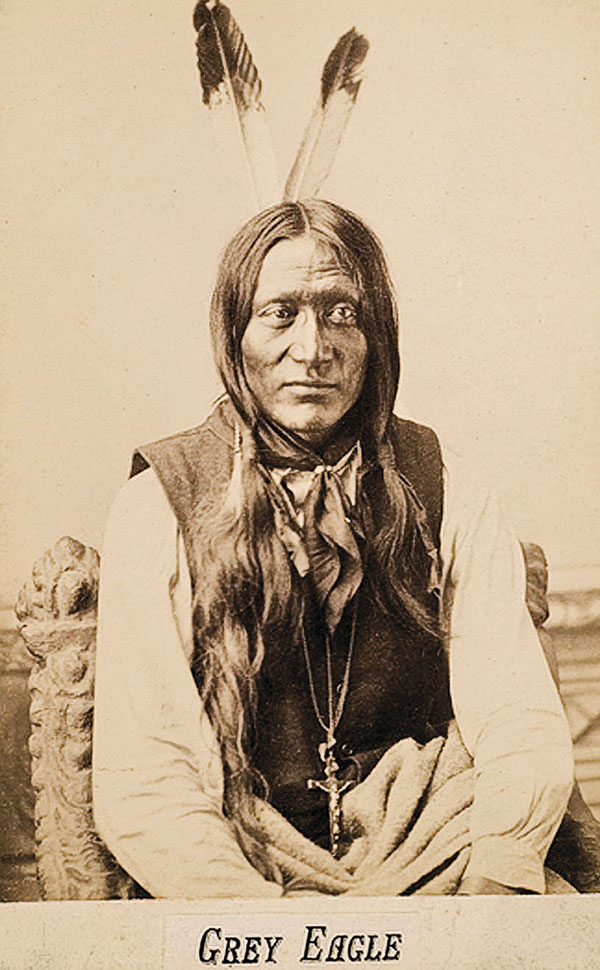

In late January 1885, Sitting Bull arrived in Bismarck, Dakota Territory, with his brother-in-law Gray Eagle. During their stay, D.F. Barry took their pictures. Both men wear a crucifix around their necks.

New research reveals that everything we know about the crucifixes they wore is wrong.

The One Bull Link

Stanley Vestal, Sitting Bull’s first biographer, linked the crucifix to De Smet. The Catholic Belgian missionary had tried to establish an “Indian State” in the Rocky Mountains area during the 1840s and 1850s. When he failed, the American government hired him to convince “hostile” Hunkpapa to sign the Treaty of Fort Laramie.

De Smet traveled to the camp without a military escort, a move deemed suicidal. Sitting Bull’s reputation at that time can be compared to that of Osama bin Laden after the attacks of 9/11.

— Courtesy Cowan’s Auctions, March 31, 2007 —

The missionary succeeded in convincing some Lakota Sioux to sign the 1868 treaty, which ended Red Cloud’s War, a bloody conflict that forced the U.S. Army to abandon all forts in Montana Territory. A treaty negotiation is how De Smet and Sitting Bull first met, on June 19, 1868, along the Powder River. They never saw each other again.

After these peace talks, De Smet gave Sitting Bull a crucifix, Vestal claimed. He wrote that the crucifix was shown in a “well-known photograph of the chief by D.F. Barry.”

Neither De Smet nor any other eyewitness of the talks wrote that the missionary had given Sitting Bull a crucifix. Vestal got his information about De Smet’s gift from two others.

Vestal recorded the testimony of Sitting Bull’s nephew One Bull in 1929: “He [One Bull] has in his possession a crucifix, which Father De Smet had presented to Sitting Bull in 1848 [sic] at Powder River Country and another crucifix he was presented by Bishop Marty, when Sitting Bull was in Canada.”

Father Martin Marty had visited Sitting Bull when he was exiled in Canada. The bishop tried to convince Sitting Bull to surrender and join his people at Standing Rock. He also wanted to convert Sitting Bull to Catholicism.

His first attempt was successful; Sitting Bull surrendered in 1881. Yet the chief refused, to his dying day, to convert to Catholicism because he did not want to become monogamous.

Eugene Little Soldier corroborated One Bull’s testimony. He was a member of the detachment of Indian Police that arrived at Sitting Bull’s cabin on December 15, 1890, to arrest him.

During the debacle, Sitting Bull was fatally shot twice.

Vestal recorded Little Soldier’s words in shorthand: “SB [Sitting Bull] not in church. SB got crucifix from miss. [missionaries] twice. 2 catholic miss. Went out. Bishop Marty came to SB in Canada.”

Both claimed Sitting Bull owned two crucifixes. One named Father De Smet as the giver; both named Father Marty. One Bull mentioned the wrong date (1848), but the correct place (Powder River).

So where are the crucifixes?

Vestal wrote about the crucifix in One Bull’s possession. In 1935, Vestal unsuccessfully tried to sell it to Albert G. Heath’s Museum of Amerind Arts in Chicago, Illinois. In a March 1957 letter, he wrote that he still owned the crucifix “which father Pierre Jean DeSmet gave him [Sitting Bull] at the treaty on Powder River. He is shown wearing this in one of the old photographs.”

One Bull’s crucifix stayed with Vestal’s family. Hayden Ausland, one of Vestal’s grandchildren, says the crucifix is now on display in the visitor’s center at the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument.

Vestal “claimed some members of Sitting Bull’s family had given him [the crucifix], telling him it was the very one that De Smet gave Sitting Bull,” Ausland says. “I myself doubt at least the identification, since some details compare only approximately with the one hanging around the chief’s neck in the well-known photo.”

— Courtesy Daniel Guggisberg Collection —

The Bullhead Link

Another crucifix attributed to Sitting Bull is on display at the State Historical Society of North Dakota museum in Bismarck, North Dakota. It was acquired by the museum in 1930 from Frank Zahn, who acted as an agent for Philip Bullhead.

On Sitting Bull’s last day of life, Philip’s father, Lt. Henry Bullhead, headed the detachment of Indian Police sent to arrest the chief. Bullhead was mortally wounded during the incident. One of his subordinates was Eugene Little Soldier.

Testimonies bolster the claim that Sitting Bull’s cabin was plundered and his body was mutilated. During the autopsy, U.S. Army Dr. Horace M. Deeble cut off a piece of Sitting Bull’s hair to save and stole his leggings.

— Bullhead crucifix courtesy State Historical Society of North Dakota; One Bull crucifix courtesy Hayden Ausland —

Another soldier stole the painting of Sitting Bull made by Caroline Weldon, a New York activist helping Sitting Bull in his struggle against the cutting up of the Hunkpapa reservation.

Several museums in the Midwest, including the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming, and the museum in Bismarck, North Dakota, own artifacts that once belonged to Sitting Bull and that were in the chief’s cabin at the time of his death.

Bullhead’s family may have owned objects stolen that day. On the other hand, no known record states Sitting Bull was wearing a crucifix when he was shot or that one was found in his cabin after his death.

The Bullhead crucifix is strikingly different than the crucifix Sitting Bull wears in the Barry photograph. “Note especially the extent of the ebony inlay beneath the memento mori,” wrote R.C. Hollow, in the article “Sitting Bull: Artifact and Artifake.”

The distance between Jesus Christ’s feet and the skull and bones is much bigger in the Sitting Bull photograph than it is on the Bullhead crucifix.

“This does not establish that our crucifix was not owned by Sitting Bull; Sitting Bull, after all, may have had a whole parflesche full of crucifixes, but the non-identity of the Zahn [Bullhead] crucifix with the one positively associated with Sitting Bull certainly does nothing to relieve healthy skepticism,” Hollow concluded.

The Sitting Bull Link

Sonja LaPointe, Sitting Bull’s great-great-granddaughter, sheds new light on the discussion. “As for the crucifix, even if Father De Smet gave him one, we do not have it. There is no proof that Sitting Bull ever owned one. Sitting Bull did not believe in Christianity, that’s why he was killed. The crucifix he was wearing in a picture belonged to his brother-in-law Gray Eagle. Gray Eagle was a Catholic and always tried to convince Sitting Bull to convert.”

Gray Eagle did indeed convert to Catholicism. He also plotted against Sitting Bull in the days before his arrest and killing.

Father Francis M. Craft, who worked at Standing Rock during the 1880s, also tried to convert Sitting Bull to Catholicism. He was asked to do so by Bishop Marty. The conversion of one of the best-known American Indians would have been a huge propaganda move for the Catholic Church. The competition between Catholic and Protestant missionaries was strong.

Marty requested as many pictures of Indians wearing a crucifix as possible. He wanted to show them to Pope Leo XIII during an official visit in April 1885, a few weeks after Sitting Bull’s and Gray Eagle’s photo shoot with Barry in Bismarck.

Barry took several pictures of Indians wearing a crucifix. Gray Eagle wears one that appears identical to the one Sitting Bull is wearing in his photo.

This corroborates LaPointe’s account: the crucifix around Sitting Bull’s neck was not one Father De Smet gave him, but one Gray Eagle hung around his neck to please Bishop Marty.

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

The Biographer’s Crucifix

Was Vestal wrong about the Sitting Bull crucifix his descendants have been preserving? Is the crucifix worn by Sitting Bull not a gift from De Smet, but one Gray Eagle gave him to wear for a photo shoot?

An examination of the crucifix worn by Gray Eagle in the Barry photo shoot reveals that his crucifix is different, not the same, as the one worn by Sitting Bull. He didn’t just loan his crucifix for his brother-in-law to wear after all. Sitting Bull had his own crucifix to wear.

The biographer’s crucifix offers a clear chain of ownership: De Smet, Sitting Bull, One Bull, Stanley Vestal and Hayden Ausland. One Bull, who lived with Sitting Bull for decades, had more opportunities to obtain the crucifix from his uncle than Bullhead or his family did. One Bull was also close to Gray Eagle.

The Bullhead crucifix provenance is more problematic. The raiding of Sitting Bull’s cabin and body is well-documented in official reports, but not one mentioned a crucifix.

Astonishing how specialists failed to compare the two crucifixes and ended up calling the “real” De Smet crucifix a “fake.”

Belgian journalist and writer Karl van den Broeck based this article on research for his 2016 historical novel, Why I Want to Save the Indians: In Search of the Cross of Sitting Bull.

Sioux, Catholics and federal government (1863-1896)

863: U.S. Army establishes Standing Rock Cantonment in Dakota Territory to oversee various Sioux bands.

July 28-29, 1864: Lakota leader Sitting Bull and trusted lieutenant Gall fight Army at Battle of Killdeer Mountain.

July 2, 1868: At the behest of Father Pierre-Jean De Smet (right), Gall and others at Fort Rice ratify Treaty of Fort Laramie, forming the Great Sioux Reservation.

1869: Grand River Agency is established. President U.S. Grant appoints Ely S. Parker as first American Indian commissioner of Indian Affairs, helping divide Indian agencies among religious denominations.

October 1871: Grand River Agency reports 7,966 Indians on reserve, based on tipis multiplied by seven.

1873: Grand River Agency moves to Standing Rock.

1874: Agency is renamed Standing Rock Agency. Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions is created to expand schools.

January 31, 1876: Fort Laramie Treaty deadline for Lakotas to move to Great Sioux reserve.

June 25-26, 1876: Sitting Bull and Gall annihilate Army Lt. Col. George Custer and 7th Cavalry at Battle of the Little Big Horn.

August 1876: Standing Rock Agency reports 1,525 on reserve, based on tipis now multiplied by five. Inconsistent data methods, as well as ignoring Indians off the reserve on hunts or trips, result in unreliable early Indian census figures.

August 15, 1876: U.S. violates Fort Laramie treaty by ceding Black Hills to the government without three-fourths of Sioux adult males agreeing.

September-December 1, 1876: Military handles oversight of Standing Rock Agency.

May 1877-1881: Sitting Bull is exiled with Gall in Canada.

1878: Great Dakota Boom begins. Up to 1887, Americans of Dakota Territory land.

Summer of 1878: Indian Affairs Commissioner Ezra Hayt removes agent William T. Hughes due to corruption charges.

October 16, 1878: Catholic Rev. Joseph A. Stephan replaces Hughes at Standing Rock, serving as both Catholic priest and civilian Indian agent.

December 30, 1878: Standing Rock Cantonment is renamed Fort Yates to honor Capt. George Yates who was killed at the Battle of the Little Big Horn.

1880: A special Indian census is authorized for Washington and Dakota Territories, and California. Standing Rock is the only Dakota reserve counted.

January 2, 1881: Gall (right) surrenders to Army at Fort Buford in Dakota Territory; David F. Barry takes the first photograph of Gall, calling it the only one he ever took of an Indian as a hostile.

March 31, 1881: Stephan gives notice of resigning as agent.

May 29, 1881: Gall arrives at Standing Rock Agency.

July 19, 1881: Sitting Bull surrenders at Fort Buford.

August 1, 1881: Sitting Bull arrives at Fort Yates at Standing Rock Agency. Gall greets him.

August 26, 1881: Dakota Indian William Selwyn takes census of Sitting Bull, Gall and others. He counts 4,293, in the first and earliest known complete census from any Lakota reservation.

September 17, 1881: After being forced to leave Standing Rock on September 10, Sitting Bull and band arrive at Fort Randall.

Fall 1881: James McLaughlin arrives as Standing Rock agent.

November 1882: Former Dakota Territory Gov. Newton Edmunds arrives at Standing Rock to negotiate a land agreement. His commission fails to secure three-fourths of adult male Sioux as 1868 treaty requires.

November 30, 1882: Gall agrees to divide Great Sioux Reservation into separate reserves, unaware Edmunds plan also opens to settlement lands not allotted to Indians. Sioux travel to Fort Randall to seek counsel from Sitting Bull, who says he doesn’t trust plan.

December 1882: Indian Rights Association is organized; one of the founders, Herbert Walsh, toured Great Sioux Reservation in summer of 1882.

May 1883: Reformers, including Massachusetts Sen. Henry L. Dawes, help defeat Edmunds plan by revealing how it concealed land cession, despite Bishop Martin Marty assuring no abuses took place at Standing Rock. Lakota John Grass testifies about abuses.

May 10, 1883: Sitting Bull returns to Standing Rock.

May 15, 1883: Under Standing Rock Agent James McLaughlin, Gall becomes assistant farmer. By September, he becomes district farmer, which he serves until 1892.

August 15, 1883: McLaughlin writes how Sitting Bull is much inferior to Gall.

September 5, 1883: Sitting Bull leads a parade to celebrate Bismarck becoming capital of Dakota Territory. McLaughlin recommended Sitting Bull for the parade, setting off a nearly two-year celebrity tour that takes Sitting Bull to New York, Washington and Canada. This includes a four-month stint with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West (see pair in photo).

July 4, 1884: Indian agents are told they must include an Indian census in annual reports.

Winter 1884-85: In 1885, D.F. Barry takes photo of Sitting Bull when he is in Bismarck, Dakota Territory, with Gray Eagle.

July 1, 1885: Census taken at Standing Rock Agency.

1887: Standing Rock census reports 4,545 Indians.

February 8, 1887: President Grover Cleveland signs Dawes General Allotment, replacing tribal land ownership with individual land ownership. Lakota population calculations claim more than half the reserve—nine to 11 million acres—will be up for grabs as surplus.

August 21, 1888: Gall gives a speech in Washington, D.C. to respond to Pratt Commission’s attempt to convince Sioux to agree to the Dawes Act.

March 2, 1889: Congress passes general allotment act to partition Great Sioux Reservation into five reserves.

July 1889: At Standing Rock, Crook Commission convinces Gall and others to sign the Sioux bill. Sitting Bull refuses to sign. The separate reservations mean Lakotas must get permission to cross land claimed by settlers to travel to kin and friends.

November 2, 1889: Dakota Territory splits, with North Dakota and South Dakota entering the Union as states.

February 10, 1890: President Benjamin Harrison signs Sioux Act into law and opens surplus land to settlers. Shortly after, the beef ration is halved. Incorrect census data from the previous two years allowed Congress to slash annual funding by roughly $1 million.

November 28, 1890: “Buffalo Bill” Cody arrives at Fort Yates to arrest Sitting Bull under Gen. Nelson Miles’s orders. Since he’s drunk, officers help him sober up and hit the road.

December 15, 1890: Sitting Bull is killed while being arrested by Indian Police under McLaughlin’s orders.

December 29, 1890: 7th Cavalry attacks Big Foot and his Lakota band at Wounded Knee Creek.

December 5, 1894: Gall dies by drinking too much of an unsafe medicine, reports his friend and photographer D.F. Barry (left).

1896: Congress decides to phase out Catholic contract schools on Indian reserves; appropriations end in 1900.