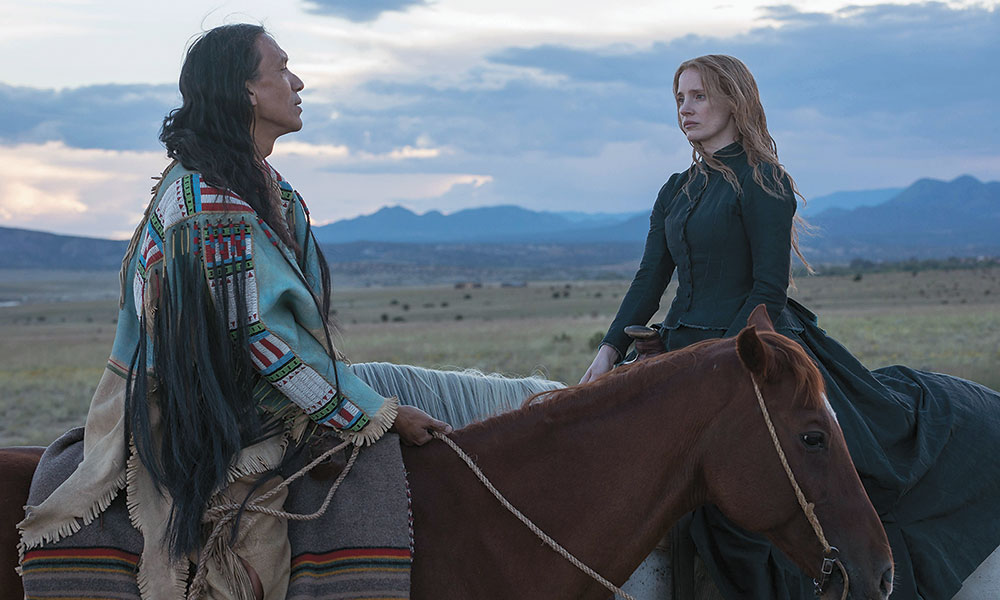

— All Woman Walks Ahead photos Courtesy A24 —

The primary job of the biographical Western Woman Walks Ahead, starring Jessica Chastain, Michael Greyeyes and Sam Rockwell, is to entertain. It succeeds admirably: the largely unknown story of Caroline Weldon (frequently misidentified as Catherine), the Brooklyn widow who became Sitting Bull’s friend and advisor, is beautifully told.

But how close is the movie to the truth, and does that matter? People nowadays seem to learn history more from fictional depictions than nonfiction and schoolkids learn less history than any previous generation. Accepting what’s presented as unvarnished truth is far too easy for folks today. After all, Wyatt Earp may have been a hero or a villain, but he’s popularly considered a hero because his history is based on a book he helped shape.

Was Weldon truly the heroine the film portrays? “She was crazy as hell at Standing Rock,” historian Robert Utley tells True West. The author of 22 volumes, including his Sitting Bull biography, adds, “She was certainly not helpful in his relations with white officialdom. Whether she was harmful in the attitudes of his own people toward his liaison with a white woman is unknown. I suspect they didn’t like the idea.”

Eileen Pollack, whose Woman Walking Ahead book was the basis for the film, doesn’t consider Weldon crazy or, even worse, a traitor in the Victorian era akin to “Hanoi Jane” Fonda in the Vietnam War era.

“This white woman had given up everything to trek from Brooklyn to the Dakotas to be an ally for people she felt had no allies and deserved them. I thought the movie captured much of that,” Pollack says.

Not that Pollack isn’t dismayed at some points the film got historically wrong. “They have her going there very naively, to paint Sitting Bull’s portrait, and then becoming politically aware and active. Weldon went there primed to help Sitting Bull fight the Dawes Act [of 1887],” which divided tribal lands into individual farms and sold the “excess” to whites.

“She’d already been sending him lists of prices for land and translating for him,” Pollack says, “being his lobbyist in Washington, D.C., working with the NIDA [National Indian Defense Organization].”

Weldon, 52, traveled to Standing Rock reservation in June 1889 and May 1890. She did paint four portraits of Sitting Bull, but the point of her visits was to act as the Hunkpapa Lakota chief’s advocate and translator.

— Weldon photo Courtesy Daniel Guggisberg Collection —

Casting made Weldon and Sitting Bull much younger than they were, probably to create a potential romance more appealing to audiences. The movie does not include Weldon’s 14-year-old son, Christie. “She brought him out; they intended to live on Sitting Bull’s homestead,” Pollack says.

“What they leave out [when we see Weldon moving in] is that [Sitting Bull’s] wives and kids were there. You see them running around, but you don’t really get who they are.”

Tragically, Christie stepped on a rusty nail, contracted lockjaw and died. “He was very close to Sitting Bull,” who had taught the boy to ride, Pollack says. “If I’d written the movie, it would have been 40 hours long and 20 times sadder. As it was, it was so sad that you could barely stand it.”

Yet the movie gets much of the history right. “The part that I thought was most effective was showing how much the whites hated Weldon for talking with the Indians, for going to live with them,” Pollack says. “The scene in which she gets beaten so badly, even though not literally true, was so emotionally true and historically true. That was a very effective [way] to portray something that I needed lots of pages to get across.”

The movie shows the extremes of white views about Indians at that time, and how far beyond the extremes Weldon stood. “The conservative position was: kill them all. The liberal position was: help them assimilate, divide up the reservations,” Pollack explains. “Weldon was one of a handful of people who had the belief that the Indians should just be allowed to be Indians.”

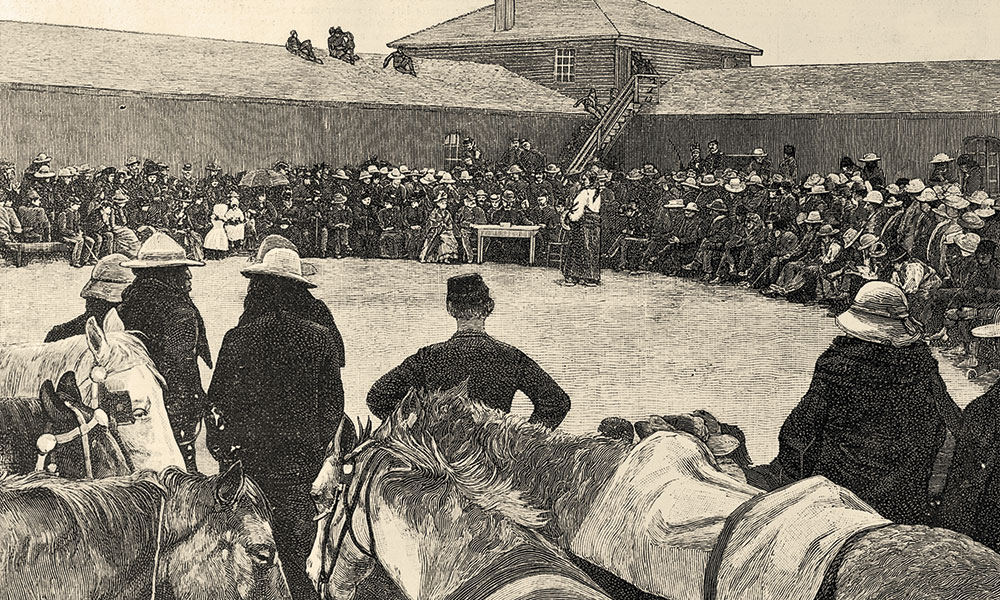

— Courtesy New York Public Library —

Indian Agent James McLaughlin is one of the more controversial real people in the story. “McLaughlin was probably the best agent in the service, his influence enhanced by marriage to an Indian woman,” Utley says. “But best agent means best at advancing civilization and best at controlling his charges.”

“I was impressed with how they portrayed McLaughlin, because he wasn’t really a villain,” Pollack says. “I’ve spoken to his grandson, who considers himself Lakota. [McLaughlin] really thought that he knew what was best for the Indians. He saw Sitting Bull as an old fuddy-duddy who was clinging to the old ways and keeping the more progressive members of the tribe from becoming assimilated.”

The best part of the story that isn’t in the movie is what Pollack learned after the book’s 2002 publication. Daniel Guggisberg, inspired by Pollack’s book, conducted research that is shared in the e-book edition of Woman Walking Ahead: “Weldon wasn’t a widow. She’d had a terrible marriage to a doctor, ran off with some guy. [Her husband] divorced her very publicly and shamefully; she was prohibited from remarrying. She was a divorcee with an illegitimate son,” Pollack says, adding that was the reason she changed her name from Susanna Karolina Faesch Schlatter to Caroline Weldon.

“So, she was just remarkable in about every way, shape and form.”

DVD Review – The Hanging Tree

(Warner Archive; $19.99) “Sluice robber!” With that bellow, and a well-aimed shot, Frenchy (Karl Malden) and a Montana boomtown mob take after the thief (Ben Piazza). He’s hidden, healed and all but enslaved by sinister, violent Doc Frail (Gary Cooper), a man with an ugly past—and a yen for a recuperating patient, played by Maria Schell. This final, enthralling 1959 Western from Director Delmer Daves brims with uncommon history and unfamiliar, yet engaging, characters.

Henry C. Parke is a screenwriter based in Los Angeles, California, who blogs about Western movies, TV, radio and print news: HenrysWesternRoundup.Blogspot.com

https://truewestmagazine.com/american-indian-historical-photos/