— Courtesy Library of Congress —

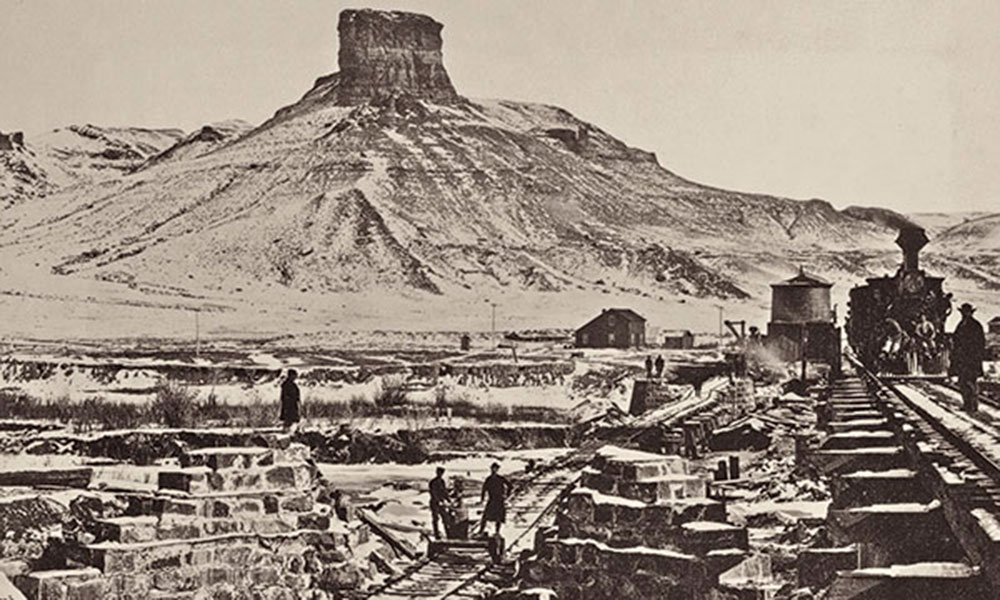

A century and a half ago the Iron Horse galloped across the prairie and plains of Nebraska then over and around the mountains and across the southern Red Desert of Wyoming, spawning a few dozen cities that remain today and dozens more end-of-tracks towns that were brief enterprises.

Thomas C. Durant, vice president and general manager of Union Pacific, president of the Credit Mobilier, and a self-serving financial strategist, managed construction, but the work started slowly. Only 40 miles of track costing more than $500,000, was in place by the end of 1865, described by a newspaper reporter as “two streaks of rust across the Nebraska prairie.” Durant hired a young Union general and civil engineer, Grenville Dodge, who had built or rebuilt railroads during the Civil War and with whom Durant had worked on railroad construction in Iowa.

Our journey begins in Council Bluffs, Iowa, at Mile 0—the eastern terminus for the Union Pacific. When in Council Bluffs visit the Dodge House, the Union Pacific Railroad Museum, and the Rails West Railroad Museum. That orientation will prepare you for the journey ahead.

— Courtesy Union Pacific Railroad Museum —

Across the Missouri, stately old Union Station in Omaha now houses the Durham Museum. At the nearby Union Pacific Museum you’ll find furniture and other items closely related to President Abraham Lincoln, who in 1862 had signed the Pacific Railway Act, leading to construction of the railroad.

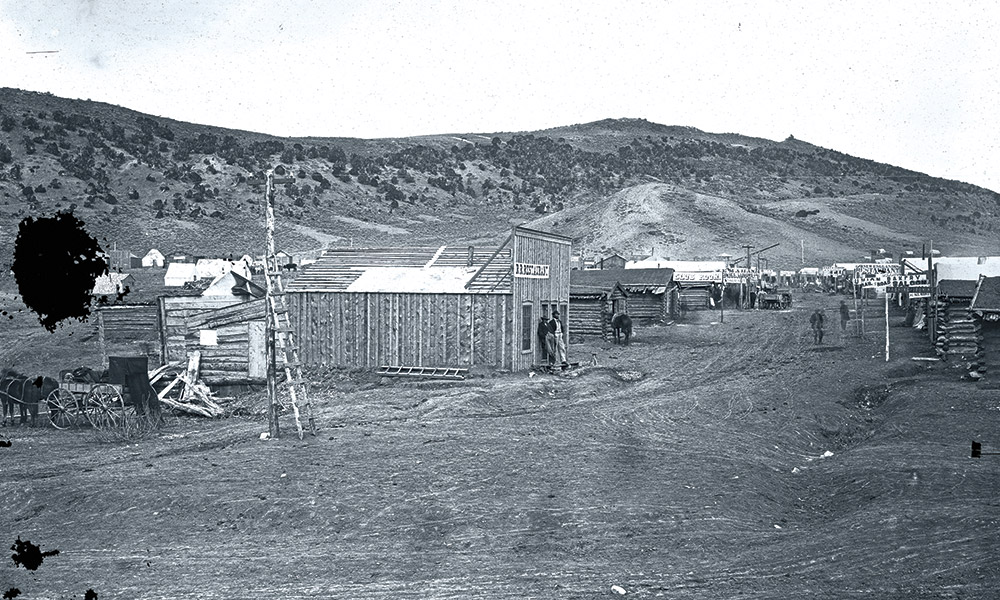

As the tracks slowly crawled west over Nebraska, William Peniston and Andrew J. Miller opened a trading post near the confluence of the North Platte and South Platte rivers, when they learned it would become a construction camp for the Union Pacific Railroad. Dodge laid out the town of North Platte and, when John Burke moved a log building in from Cottonwood Springs to serve as a hotel, North Platte’s birth was complete. Soon the first newspaper, The Pioneer on Wheels, began publication in a boxcar. By the winter of 1866-’67 North Platte’s population swelled to 2,000 railroad workers and camp followers.

It was described by the Missouri Democrat in May 1867 as a “gay frontier hamlet; its citizens a motley crowd of construction camp denizens, roughs, and gamblers, emigrants but a few months from the countries of the Old world. Women from the dance halls, bullwhackers and teamsters.”

By June 1867 the Union Pacific track crews had pushed on west to Julesburg, Colorado, and the population of North Platte collapsed to just 300 citizens. But it remained and regrew after the Union Pacific made it a division point for the railroad; by 1879 North Platte had rebounded to 1,600 residents.

— Courtesy Nebraska Tourism —

Dan and Jack Casement managed the track-laying crews who lived in 20 cars that had dormitory facilities. The workers—track layers, teamsters, blacksmiths, carpenters, mechanics and masons—worked 12 to 16 hours a day and earned an average of a dollar a day.

The Union Pacific pushed into Wyoming. On July 9, 1867, six men and three women set up a camp that became Cheyenne. One early resident said, “Well, one fine day in early July, 1867, four or five hundred of us pitched our tents here, where there wasn’t a sign of civilization, and about half of us woke up at daylight the next day to find that the other half was living in board shanties!” This rapid growth quickly gave the town the name “Magic City of the Plains.” It grew to 4,000 residents, and in 1868 became the capital of Wyoming Territory. The original UP Depot now houses businesses and a railroad museum.

The rail line pushed west past Cheyenne and the terrain changed. Once across the Sherman summit, named for Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, the railroad dropped into the Laramie Valley where Fort John Buford had been built in July 1866. The city of Laramie—Gem City of the Plains—would grow into almost immediate prominence, ultimately the home of the Wyoming Territorial Prison, now a state historic site.

The Union Pacific, now running parallel to the earlier established Overland Trail, pushed west with end-of-tracks towns popping up every 20 miles along the route. They included Carbon, the first coal production center on the UP railroad line; Fort Steele, a military post established to protect the railroad construction crews from Indian attacks; and Benton, which quickly grew to 3,000 residents with a city government and a daily newspaper.

— Courtesy Wyoming Office of Tourism —

As the tracks circumnavigated the Medicine Bow Mountains and prominent Elk Mountain, it became far easier to obtain railroad ties. Camps in the mountains as far south as the Sierra Madre put thousands of tie hacks to work from the earliest days of UP construction until well into the 20th century because ties were continually needed for track maintenance. The history of the area tie camps is a prominent feature at the Grand Encampment Museum.

Rawlins, named for Gen. John A. Rawlins, blossomed because of a spring of good water at the site, and it soon eclipsed Benton, ultimately becoming the county seat.

The Union Pacific crossed the Great Divide Basin and inched its way to Rock Springs, which became a major coal supply center, and Green River, which also became a division point for the Union Pacific.

In late November 1868, Harvey Booth pitched a tent, opening a saloon and hotel in what would become Evanston. The Union Pacific track-layers reached his little enterprise on December 1 and the 600 camp followers and construction workers quickly overwhelmed Booth’s accommodations. Soon houses of wood and canvas went up to serve the new population.

Evanston almost died as quickly as it was born when the Union Pacific moved headquarters to Wasatch, Utah. Within a day most people and businesses abandoned Evanston and moved on. But in June 1869, the UP, recognizing the availability of a steady water supply from the Bear River, reestablished division headquarters in Evanston, ultimately building a major maintenance facility there as well, permanently placing Evanston on the map.

Coal mines that opened just north of Evanston attracted a large population of Chinese miners who established their own community—a shantytown built of scrap lumber, tar paper, packing boxes and even flattened metal cans—north of the railroad tracks. These Chinese residents worked in the mines, operated laundries, and peddled vegetables they grew in large gardens. They also built a joss house—one of three in the United States at the time—where they could practice their religion. While the original joss house burned in 1922, a replica now serves as a museum.

By the end of 1868 the Union Pacific had laid track all the way west from Omaha to Evanston, and was poised for the final stretch across Utah in order to meet the Central Pacific track being laid from California. The two lines would ultimately be joined at Promontory Summit in northern Utah in May 1869.

— Courtesy Wyoming Office of Tourism —

Side Roads

Places to Visit

Council Bluffs, Iowa: Grenville Dodge House, Golden Spike Park; Union Pacific Railroad Museum; Rails West Railroad Museum

Nebraska: Durham Museum and Union Pacific Museum, Omaha; Lincoln County Historical Museum and Golden Spike Tower and Visitor Center, North Platte

Wyoming: Cheyenne Depot Museum, Cheyenne; Ames Monument, Exit 329 Off I-80 between Cheyenne and Laramie; Wyoming Territorial Prison State Historic Site, Laramie; Medicine Bow Museum, Medicine Bow; Grand Encampment Museum, Encampment; Carbon County Museum, Rawlins; Sweetwater County Historical Museum, Green River; Chinese Joss House Museum, Evanston

Best Eats & Sleeps

Grub: Drover, Omaha, NE; Canteen Bar & Lounge, North Platte, NE; The Cavalryman, Laramie, WY; Rose’s Lariat, Rawlins, WY; The DiVide, Encampment, WY; Don Pedros, Green River, WY

Lodging: Magnolia Hotel, Omaha, NE; Nagle Warren Mansion, Cheyenne, WY; Little America Hotel, Cheyenne, WY; Elk Mountain Hotel, Elk Mountain, WY; Best Western Dunmar Inn, Evanston, WY

RV Parks and Campgrounds

Holiday RV Park & Campground, 601 Halligan Dr, North Platte, NE, HolidayParkNE.com,

(308) 534-2265; Pine Grove RV Park and Campground, 23403 Mynard Rd, Greenwood, NE, PineGroveRVPark.com, (402) 944-3550; Laramie KOA Journey, 1271 W Baker St, Laramie, WY, KOA.com, (307) 742-6553; Western Hills Campground, 2500 Wagon Circle Rd, Rawlins, WY, WesternHillsCampground.com, (307) 324-2592

Good Books, Films & TV

Books: Roadside History of Nebraska by Candy Moulton; Hell on Wheels: Wicked Towns Along the Union Pacific Railroad by Dick Kreck; Roadside History of Wyoming by Candy Moulton

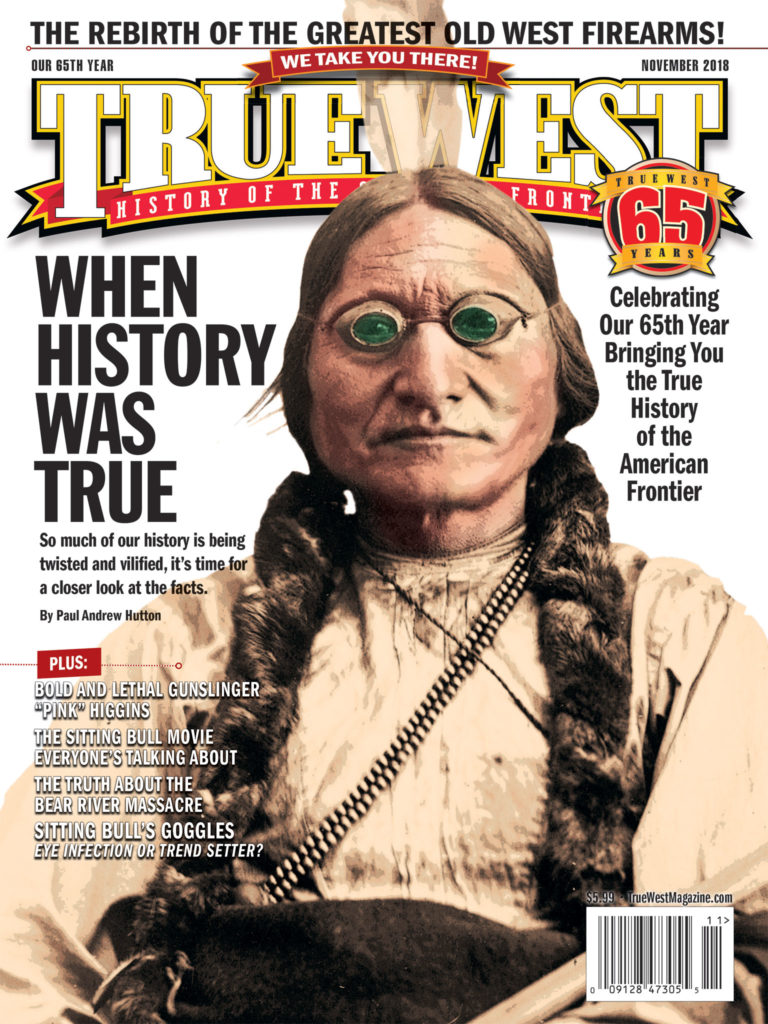

Film & TV: The Iron Horse (Fox, 1924), Union Pacific (Paramount, 1939), How the West was Won (MGM, 1962), Hell on Wheels (AMC, 2011-2016)

Candy Moulton is the author of Roadside History of Nebraska and Roadside History of Wyoming.

https://truewestmagazine.com/train-ride/