— By Maura Dhu Studi —

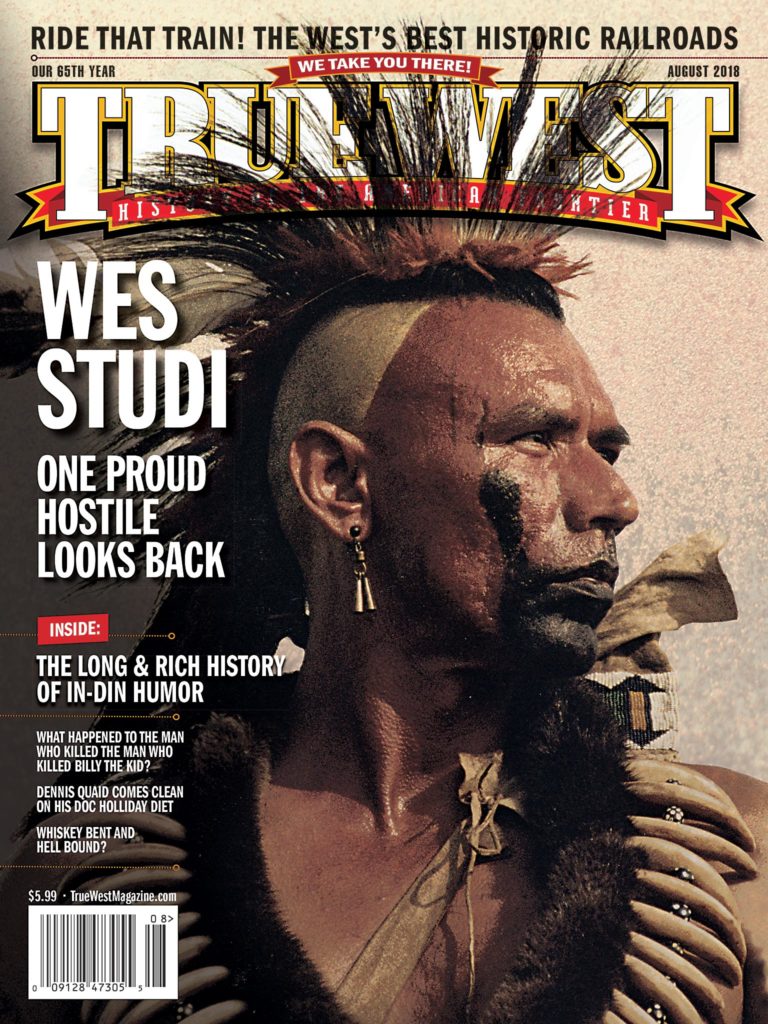

Wes Studi, fresh from the success of Hostiles, appeared on the 2018 Oscars to present a movie montage highlighting military service, the 70 year old mentioned that he’d volunteered for Vietnam, and asked if anyone else had.

He was met with silence.

“I wasn’t surprised,” he told True West, with a chuckle. “I said it as a joke. I know the audience is not full of veterans, and their attitude toward veterans is not probably as complimentary as you’d find in other audiences.”

He concluded his introduction with words in Cherokee, his native language. “It was to Cherokee veterans, as well as all military veterans, kind of a shout-out that it’s a good day.”

It was indeed a good day for veterans and American Indians. While this year, much was made of the racial diversity of nominees and the strides of women, most viewers were unaware that Studi was the first American Indian to be a presenter since fellow Cherokee Will Rogers hosted the Academy Awards in 1934.

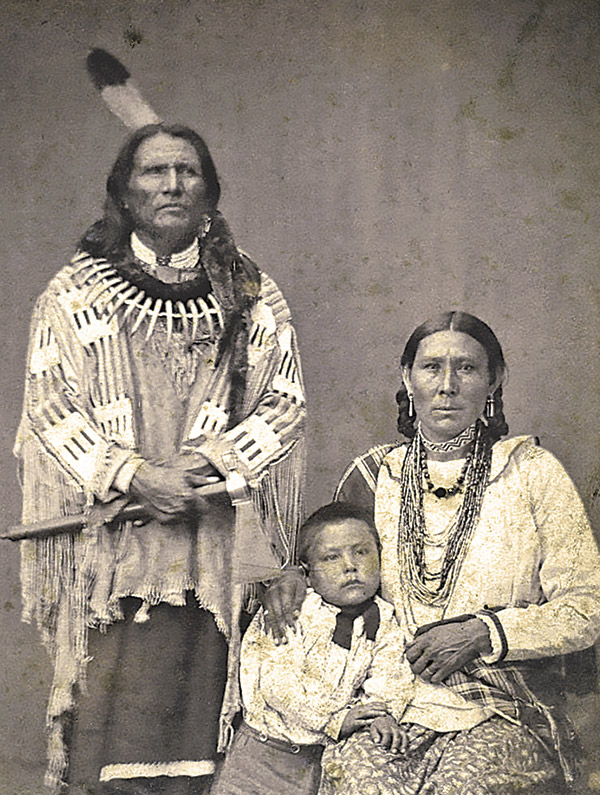

— Courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society —

Although lacking Oscar nominations, the critical and popular success of Hostiles, now available on Blu-ray and 4K, is no mystery to Studi.

“What sets Hostiles apart for me is simply the story. I think it speaks not only to the old Western of yesteryear, [but also] to the world we live in today.

“There’s been a dearth of Westerns on the big screen for a number of years because nobody’s been able to make a successful one since, say, Unforgiven. It’s been a long time, and Western fans have been hungry for another one.

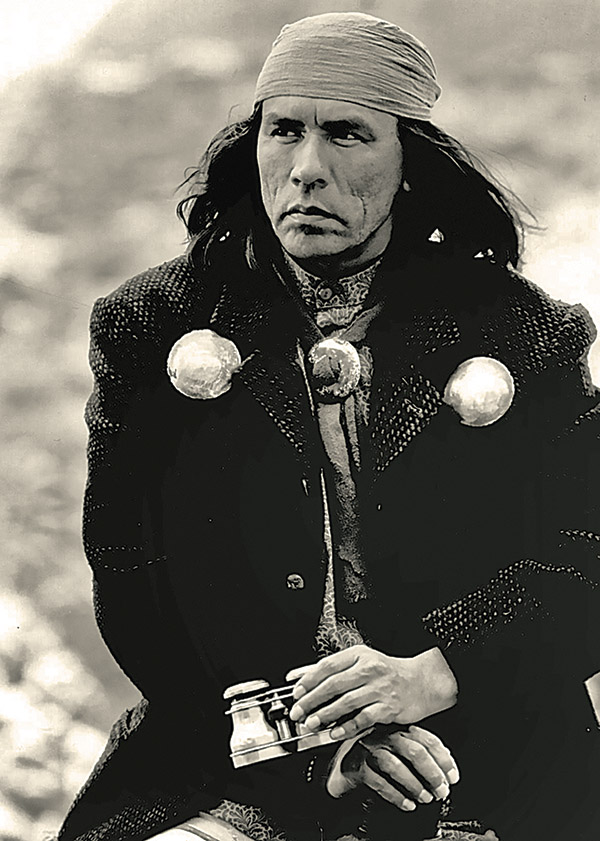

— By Erik Heinila, Courtesy Turner Pictures —

“Along comes Hostiles, and she’ll go for another ride. I think we’re probably going to see a few more in the next few years.

“It was good to work with Christian [Bale] again. There was a threesome of us—Christian, Q’orianka [Kilcher] and myself —who had worked on The New World. Rosamond Pike, I think she’s a wonderful actor. [Writer/Director] Scott [Cooper] was extremely open to ideas, and had a good grasp of where he was going with the story.”

Playing Studi’s character’s son was Adam Beach, who’s shared the screen with Studi a dozen times.

“He’s played my son to good effect and not so good effect at times,” Studi says. “He killed me in Comanche Moon, and there was another one that he played my son and killed me. I think he gets a kick out of that.”

— Courtesy Nebraska State Historical Society —

Then 25 years ago, Studi starred as Apache leader Geronimo, in Geronimo: An American Legend, who surrenders to the Army in the end; in Hostiles, he plays Cheyenne war Chief Yellow Hawk, who is freed from U.S. Army custody and transported to his homeland to die.

“There’s a continuity because the Cheyenne share an experience in dealing with the American military and the American government itself,” says Studi, adding ironically, “They don’t work hand in hand. The result being the kind of situations that our fictional character Yellow Hawk, and the real character Geronimo, ran into and had to deal with, and [we] continue to do so to this day.”

Technically, Studi was born in Nofire Hollow, Oklahoma, on December 17, 1947. However, “The Cherokee Nation is where I was born, and my first language was Cherokee. That’s what we spoke in the home. When I went to school, I learned English,” he says.

“My parents did a lot of different things. The whole family raised crops and hunted, and survived in a way that people hardly do anymore. We bought salt and flour from the store. But we raised almost everything or hunted for it. Then my dad started working on ranches; that was pretty much his life and the whole family’s life, living from one ranch to another in northeastern Oklahoma. We weren’t living high off the hog.”

In 1960, Studi’s parents sent him to boarding school. “It was called Chilocco Agricultural School, and that’s where my dad had learned most of his expertise in farming. I learned other things. We did half a day of academic work and half a day of vocational work, which was dry cleaning. It was a government Indian school.”

Chilocco was originally one of the controversial institutions that tried to teach the Indian culture out of its students. “By the time I went there, things had changed. [We were] still discouraged from speaking our own languages, but it wasn’t cracked down upon like it had been. The fact that a lot of Indians were involved in the administration of the school, and teaching, made a huge difference.”

Studi enlisted in the National Guard in high school and entered the Army after graduation. “I volunteered to go to Vietnam. I was an infantryman. We sought out the enemy, sometimes search and destroy, sometimes defend. For a while I was the RTO; I carried a radio for the platoon leader.”

Despite the uniform, the physical differences between Indian soldiers like Studi and other soldiers were noticed by the Vietnamese. “They said they saw us as being very similar to the Vietnamese, you know? Because we kind of looked like them; our skin color was the same. And if they knew our history, they [knew] that we had been fighting the U.S. Army just like they were at that point in time.”

— By Sam Emerson, Courtesy Columbia Pictures —

In the highly political Western films made during the Vietnam era, the treatment of Indians was used as a symbol of the U.S. treatment of the Vietnamese. “Yeah, I think it was legitimate,” Studi confirms. “I mean, we’ve all been the enemies of the U.S. military. That may be hard for you to understand, but we’ve all been in that position.”

The 1970s were an active time for Studi, who had returned from Vietnam in 1969. He attended Northeastern State University in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, on the G.I. Bill. Later, he would teach the Cherokee language there and within the community. He helped revive The Cherokee Phoenix, founded in 1828, the first newspaper established by Indians and published in Cherokee and English. He also became involved with A.I.M.—the American Indian Movement.

“The ‘Trail of Broken Treaties’ is when it started for me, in terms of activism,” Studi recalls of the 1972 cross-country protests that culminated in Washington, D.C., just before the Presidential election.

— Courtesy Entertainment Studios Motion Pictures —

Studi also went to Wounded Knee, where he was among those arrested in 1973. “The larger idea was to work toward a realistic approach to tribal sovereignty, and [we] continue to do so to this day.

“Russell Means was one of the leaders of the American Indian Movement, so I knew, and knew of, him back in the activist days of the ’70s. And then we wound up on the film set of Last of the Mohicans in the ’90s.”

Studi’s interest in acting began in the 1980s. “I decided to try at a community level and found that I liked it. That led to real theatre, led to educational television. I decided Los Angeles was the only recourse if I were to continue this line of work.”

He made a powerful impression as the Toughest Pawnee in 1990’s Dances With Wolves, which led to one of his most unforgettable characterizations, in Last of the Mohicans.

“Actually, when I slipped in to have an interview for Magua, I ‘inadvertently’ left a picture of myself from Dances With Wolves on somebody’s desk,” he recalls, with a laugh. “I don’t know if it helped or not. After Last of the Mohicans, I continued to work.”

That’s putting it mildly. Studi has acted on-screen in more than 90 productions around the world. Recently, he costarred in season three of Showtime’s Penny Dreadful.

“Oh, that was a great job. Got to travel in Europe to Ireland and southern Spain. Where we worked was [Sergio] Leone-land, they call it. In fact, we worked in one of his old set towns. There are some subtle differences in the terrain in Spain, but only people from New Mexico or the Southwest can really figure out. I think it works pretty well.”

He’s worked on a number of films with his wife, documentary filmmaker Maura Dhu Studi, most recently Defending the Fire, an examination of the warrior in American Indian culture, which is currently playing on PBS stations.

“I don’t know if you’d call it a Western or not, but one of my favorite films that I’ve done is called The Only Good Indian.”

Set in 1900 Kansas, the 2009 film showcases Studi as an Indian bounty hunter, chasing down an Indian boy who’s run away from a government school. “I’m pretty proud of having been a part of it.”

Over the years, Studi has played many legendary chiefs, including Geronimo, Red Cloud, Crazy Horse, Buffalo Hump, even Cochise in A Million Ways to Die in the West.

“It carries a special responsibility. I’m going to have to play the character as he’s written, and then also keep in mind that there are family memories and whether he was an icon.

“During Geronimo, we were playing with descendants of his. It’s something that you have to be careful with, that’s part of the whole process, putting together a character.”

With several films now in the editing stage, and others preparing to film, Studi shows no interest in slowing down.

“I continue to like it, and I will do it until the day I die.”

As far as Westerns goes, Studi remains confident of the genre’s power over audiences, saying, “I think almost every director is going to try a Western, if they have any balls.”

Native Oscars

1934: Will Rogers hosted the Oscars.

1971: Chief Dan George was nominated for “Best Supporting Actor” for Little Big Man.

1973: Sacheen Littlefeather, a half-white Apache-Yaqui, represented Marlon Brando when he declined his “Best Actor” Oscar for The Godfather in protest against the portrayal of American Indians in movies.

1982: Buffy Saint-Marie shared the “Best Song” Oscar for “Up Where We Belong,” from An

Officer and a Gentleman.

1991: Graham Greene was nominated for “Best Supporting Actor” for Dances With Wolves; film consultant Doris Leader Charge translated Michael Blake’s remarks into Lakota Sioux when he accepted his Oscar for “Best Adapted Screenplay” for Dances With Wolves.

2018: Wes Studi made history as the ceremony’s first American Indian presenter. While introducing a film montage that honored military service, he spoke Cherokee. (Translation: “Hello. Appreciation to all veterans and Cherokees who’ve served. Thank you!”)

Wes Studi’s Popular Westerns

Out of the 35 Westerns Wes Studi has appeared in so far, the 10 ranked the most popular by IMDB.com are:

1. 2017’s Hostiles:

Chief Yellow Hawk

2. 2011 & 2012 Hell on Wheels:

Chief Many Horses

3. 1990’s Dances With Wolves:

Toughest Pawnee

4. 2014’s A Million Ways to Die in the West:

Cochise

5. 2005’s Into the West:

Black Kettle

6. 1993’s Geronimo: An American Legend:

Geronimo

7. 2006’s Seraphim Falls:

Charon

8. 2008’s Comanche Moon:

Buffalo Hump

9. 2007’s Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee:

Wovoka

10. 2014’s Killer Women:

White Deer

Henry C. Parke is a screenwriter based in Los Angeles, California, who blogs about Western movies, TV, radio and print news: HenrysWesternRoundup.Blogspot.com

https://truewestmagazine.com/hostiles-deeply-felt/